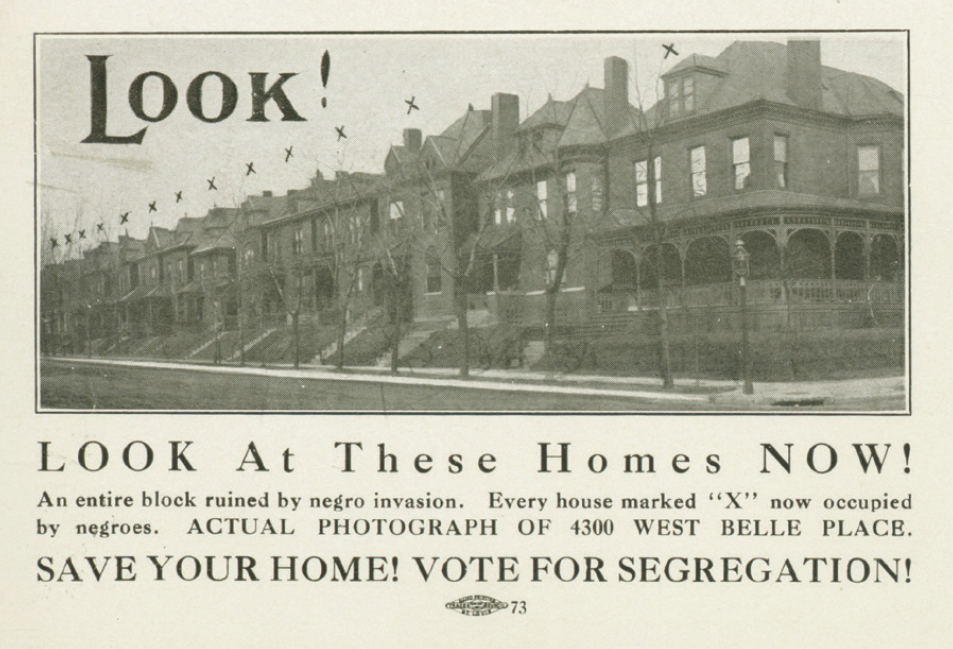

Introduction: 19th and Division, 1954

The illusion conjured by modern segregation is that segregation is a totalized reality, a natural and normal state of affairs. It is only by the close visual and historical engagement with material sites of segregation as palimpsests, in the manner this volume models, that the precariousness of the segregationist project in St. Louis can be discovered.