“The Theater must always be a safe and special place.”

—President-elect Donald J.Trump, tweeted November 19, 2016¹

“The work is all about comfort for the living. ‘Blessed are they that carry sorrow, for they shall be comforted.’”

—Amy Kaiser, Director of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus, program notes for Brahms, Ein Deutsches Requiem, October 4, 2014²

On November 18, 2016, Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended the wildly popular musical Hamilton at Broadway’s Richard Rodgers Theater. At the show’s end, Brandon Victor Dixon, the African-American actor playing Aaron Burr, directed prepared remarks from the stage to Pence as he headed for the exit. “We, sir—we,” Dixon asserted, “are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights.”³ Donald Trump responded with a series of tweets complaining that Pence had been “harassed” and that the Hamilton cast “was very rude last night to a very good man.”⁴ Some of Trump’s detractors mocked him for hypocrisy in calling for a “safe and special place,” a term that recalled the “safe spaces” supposedly demanded by oversensitive liberal undergraduates and pilloried by Trump advocates such as Breitbart.⁵ Even Trump, who built his campaign on his aversion to “politically correct” modes of speech and behavior, seemed to feel that traditional rules of decorum still applied at the theater—or, more cynically, he understood that his supporters would embrace that premise in order to cheer his attack on Dixon.

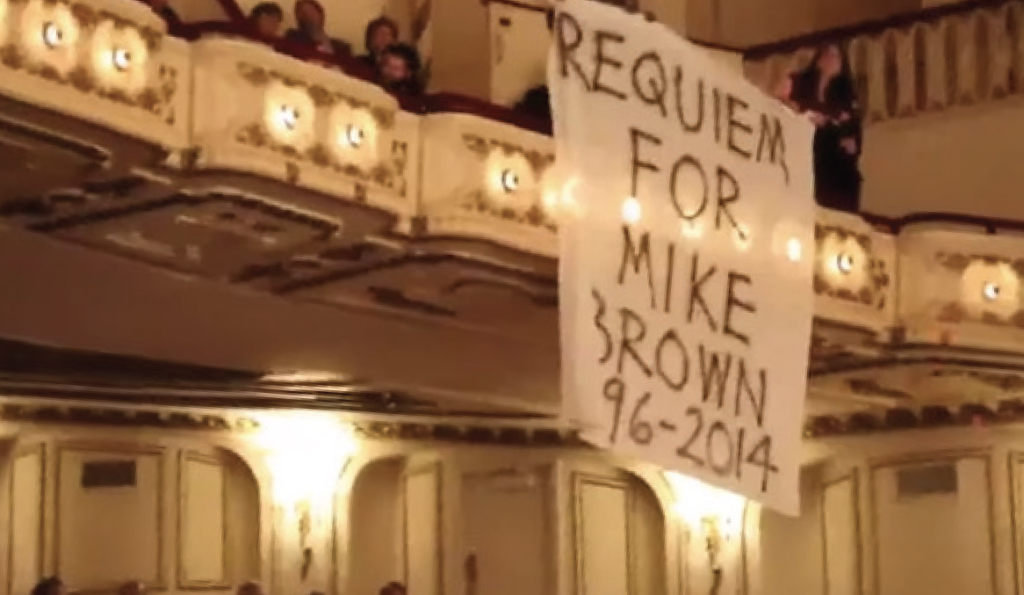

For observers following the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, the Hamilton incident and Trump’s response recalled another event from two years earlier. Powell Hall (718 North Grand Boulevard) has since 1968 been the home of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. The venue received unusual international attention on October 4, 2014, when local activists, responding to the recent shooting of Ferguson resident Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson, staged a demonstration during the intermission before a performance of Brahms’s A German Requiem. The protesters unfurled banners reading “Racism Lives Here,” “Requiem for Mike Brown 1996-2014,” and “Rise Up and Join the Movement” and sang the 1930s union anthem “Which Side Are You On,” with lyrics updated to address Brown’s death. Afterward, the singers, chanting “Black Lives Matter!” marched in pairs out of the hall and the orchestra continued with its program.⁶

Although some commentators treated the action as an invitation to explore the facts of the Brown case and community responses to it, many also raised the seemingly less pressing question of whether Powell Hall should remain a “safe and special place” free from protest. Predictably, those opposed to civil rights protest regardless of its context disapproved of the activists. White nationalist blogger Michael J. Thompson, assuming incorrectly that the protesters were all African Americans and therefore (by his racist illogic) potential murderers, reported that “those preaching ‘Requiem for Mike Brown’ asked the audience: ‘Whose side are you on?’ A terrifying question, when you consider the answer you give could result in the taking of your life (terrorism at its finest…and you’re worried about ISIS?).”⁷ But decent, thoughtful observers also expressed concern. In a letter to the editor of the Post-Dispatch, Dana Edson Myers, a first violinist in the orchestra, asked “Is Powell Hall a proper venue for a protest? I assume the protesters bought tickets for this opportunity to have their voices heard. What comes next? Can we expect such events to happen at the art museum? At Circus Flora? At a school graduation? The experience saddened me profoundly. Just like the Ferguson situation, I was left tensely unresolved.”⁸ Myers does not seem to be criticizing the protest but rather grieving the loss of a supposedly more innocent time when St. Louis’s most contemplative or artistic settings provided refuge from harsh realities of the city.

Figure 1: Black Lives Matter protest at Powell Hall, October 4, 2014.(YouTube)

The activists themselves framed their actions in terms of safety and comfort. On the one hand, the protest was intended to discomfit apathetic symphony-goers. Derek Laney of Missourians Organizing for Reform and Empowerment explained that protesters wanted to “speak to a segment of the population that has the luxury of being comfortable…You have to make a choice for just staying in your comfort zones or will you speak out for something that’s important? It’s not all right to just ignore it.”⁹ Organizer Sarah Griesbach, a White resident of the Central West End, explained that she hoped to trouble other White St. Louisans: “It is my duty and desire to try to reach out and raise that awareness peacefully but also to disrupt the blind state of white St. Louis, particularly among the people who are secure in their blindness.”10 At the same time, however, Griesbach and co-organizer Elizabeth Vega had chosen Powell Hall because it was likely to be a reasonably accepting venue for their message. Two weeks before, they had been “booed and handcuffed after hanging banners at a St. Louis Cardinals game.” CNN reported that “as they were escorted out of the stadium in handcuffs, Griesbach joked, ‘We probably need a different venue.’”11 Griesbach explained the choice of Powell Hall, where “the audience was fairly diverse in ethnicity and age,” by saying that “there is an inclusivity that comes with that intellectual culture.”12 This suggests that classical music lovers presumably hold humanist values to which a protest might appeal. Vega added that “many of us are artists ourselves, so we were very cognizant to not interrupt the performance after it had already began…But we still wanted it to be a disruption that left people with a seed of thought.”13

But why this assumption, shared by the protesters and their critics, that disruptive behavior at the theater was abnormal? Some of Mike Pence’s critics mordantly “compared his experience with Abraham Lincoln’s, who had, undoubtedly, a worse time at the theater.”14 Or consider the 1849 riot at New York’s Astor Place Opera House, which began with a populist audience hurling eggs at snooty British actor William Charles Macready and ended three nights later with twenty-two deaths after soldiers fired into the unruly crowd surrounding the venue.15 Historian Lawrence W. Levine has demonstrated that by the end of the nineteenth century such incidents had become rare in “highbrow” settings, as wealthy White elites threatened by increasingly diverse cities and working-class immigrants promoted the “sacralization” of high culture and achieved “general success in disciplining and training audiences” when not excluding undesired groups altogether.16 Theaters began to adopt design features—permanent single seats rather than movable benches, electric lights that could be dimmed to focus attention on the stage rather than the audience—that encouraged the audience to think of itself not as a collective but rather as “a mass of separate individuals ‘spell-bound in darkness,’” as Richard Butsch puts it.17 Powell Hall and its audiences both rely upon and reinforce this venerable tradition of disciplined attention to (mainly) European masterworks in a comfortable, genteel space.

Historian Lawrence W. Levine has demonstrated that by the end of the nineteenth century such incidents had become rare in “highbrow” settings, as wealthy White elites threatened by increasingly diverse cities and working-class immigrants promoted the “sacralization” of high culture and achieved “general success in disciplining and training audiences” when not excluding undesired groups altogether.

Tracing Powell Hall’s history, however, uncovers shifting concerns about safety and comfort more specific to the urban geography of St. Louis. I turn now to two key moments—the venue’s opening as the St. Louis Theater in 1925 and its debut as Powell Hall in 1968—that reveal that the hall’s predominantly White patrons have long held anxieties about racial segregation. The “Requiem for Mike Brown” protest was powerful in part because it evoked the hall’s repressed, uncomfortable history of racial exclusion and exposed the hall’s role in constructing what George Lipsitz terms a “white spatial imaginary” that “idealizes ‘pure’ and homogeneous spaces, controlled environments, and predictable patterns of design and behavior” and “seeks to hide social problems rather than solve them.”18 Lipsitz illustrates that “African American battles for resources, rights, and recognition not only have ‘taken place,’ but also have required blacks literally to ‘take places.’”19 By “taking” Powell Hall, if only briefly and peacefully, the protesters called the White spatial imaginary into question and challenged St. Louisans to reflect on the relationship between the rarified experience of an orchestra concert and the struggles taking place outside.

Figure 2: St. Louis Theater, 718 N. Grand Avenue, circa 1933. (Missouri Historical Society)

A certain kind of respectability

The St. Louis Theater, a vaudeville and movie palace associated with the Orpheum Circuit, opened on November 23, 1925. With 4,080 seats, it became the largest auditorium in the city. The souvenir program for the theater’s premiere performance emphasized the audience’s “health, comfort, and safety,” touting its superior heating and cooling system and its “overstuffed chairs of commodious design” and assuring patrons that “the St. Louis is absolutely fireproof and is amply provided with exits.”20 Its architects, the Chicago firm Rapp and Rapp, aspired to evoke a spirit of European elegance. The Post-Dispatch hailed the new theater’s lobby as “a replica of the chapel in the palace of Versailles near Paris,” lit by opulent chandeliers “shooting 220 lights apiece through crystals taken from the pure sands of Czechoslovakia.” More recently, the Landmarks Association of St. Louis has described the building as a “movie palace fantasy version of the French Renaissance.”21 The entertainment offered in this lavish setting, however, was decidedly low- to middlebrow. The inaugural performance, for example, included Allen White’s Collegians in “Youth, Pep, and Harmony”; Arthur Lange’s “jazz arrangement” of Gounod’s Faust; Singer’s Midgets and their trained elephants, ponies, and dogs in the revue “So This Is Lilliput”; and a feature film, the melodrama Drusilla with a Million.22 The theater was dedicated to providing popular, accessible entertainment in a setting of refined comfort that served to confirm its patrons’ sense of their own sophistication; as film scholar Charlotte Herzog observes generally of 1920s movie palaces, “the popular flavor of the theater enjoyed a new distinction, thanks to the veneer of a certain kind of respectability.”23

By “taking” Powell Hall, if only briefly and peacefully, the protesters called the White spatial imaginary into question and challenged St. Louisans to reflect on the relationship between the rarified experience of an orchestra concert and the struggles taking place outside.

This “certain kind of respectability” assumed the superiority of European culture and relied on racial segregation. Although Black performers such as blues singer Ada Brown and the piano-vocal duo Tabor and Green appeared in live vaudeville shows during the St. Louis Theater’s first year of operation, Black patrons appear to have been barred altogether.24 Although I have not located any source explicitly stating the St. Louis Theater’s racial policies, the Baltimore Afro-American praised Black entertainer Sunshine Sammy in 1929 for “stepp[ing] from the stage of the St. Louis Theatre, white, last week to entertain pupils of Sumner and Vashon high schools who were barred from witnessing their performances down town.”25 The St. Louis Argus, the city’s main African-American paper, made no mention whatsoever of the St. Louis Theater or its grand opening between November 20 and December 25, 1925, while providing consistent coverage of, and advertising for, those theaters where their readers were welcome. White patrons of the St. Louis Theater could indulge their fantasies of Versailles in part because Jim Crow policies blocked out the racial inequality of the surrounding city.

Figure 3: Entrance foyer of the St. Louis Theater, 1920s. (Missouri Historical Society)

The safest place in town

Four decades later, when the St. Louis Theater became Powell Hall, the demographics of the city had changed significantly. “Between 1950 and 1970,” as historian Colin Gordon demonstrates, “close to 60 percent of the (1960) white population fled the City” as “the locus of white settlement…moved to the western reaches of St.Louis County.”26 The predominantly Black neighborhoods directly north and east of the theater had become synonymous with urban redevelopment, famously epitomized by the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, a mile and a half away, which had begun accepting tenants in 1954.27 Gordon explains that by 1969, when HUD’s Model Cities program began providing development funds targeted at this area, its borders already encompassed “a number of areas previously blighted and redeveloped under other programs, including the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex, the Grandel Redevelopment Area, and the DeSoto-Carr Redevelopment Area. Population of the area was about 70,000, and rates of unemployment, vacant housing, and reliance on welfare ran at about twice the citywide averages.”28

By 1966, the St. Louis Symphony Society, weary of sharing Kiel Auditorium with sports events, had begun to consider purchasing and converting the St. Louis Theater into a dedicated space for the orchestra. On April 4, 1966, Stanley J. Goodman, president of both the May Department Stores Company and the Symphony Society, reported that the City Planning Commission “greatly favored the St. Louis Theatre site because Grand Avenue and that area is marked for redevelopment as one of the next important City projects.” The Symphony Society’s Executive Committee voted to recommend to the Society’s Board that the theater be purchased and remodeled, “providing that contingent difficulties, such as the parking problem could be solved satisfactorily.”29 On April 6, the Board unanimously approved this plan.30 The City Plan Commission of St. Louis endorsed the proposal on April 28, noting that “the proposed concert hall at Grand and Lucas would be in harmony with several of the schemes suggested for the new ‘Grand Center’ in the Central West End Plan.”31 In August, the Symphony Society purchased the theater for $388,475 with a donation from Oscar Johnson, Jr., heir to the founder of the International Shoe Company and formerly the Society’s president.32 The Post-Dispatch reported that “renovation and remodeling are expected to cost in excess of $1,000,000, to be paid for out of funds collected in a $4,000,000 capital fund campaign now under way by the Symphony Society.”33 Donors including local chemical company Monsanto; the Beaumont Foundation, whose namesake had cofounded May Department Stores; the Arts and Education Council, a nonprofit started in 1963; Helen Lamb Powell, who set up a $1,000,000 trust fund in honor of her late husband Walter S. Powell, former director of Brown Shoe Company; and a matching grant from the Ford Foundation enabled the Symphony Society to reach its fundraising goal.34

White patrons of the St. Louis Theater could indulge their fantasies of Versailles in part because Jim Crow policies blocked out the racial inequality of the surrounding city.

As Powell Hall underwent substantial remodeling, so too did the surrounding neighborhood. In March 1967, a Post-Dispatch editorial announced:

Washington housing authorities have approved a grant of $424,688 for the Grandel urban development in St. Louis…a key area in the geography of St. Louis renewal…Generally speaking, this project will link up the new, park-like children’s center, the veterans’ hospital and the Blumeyer apartments now nearing completion. Thus it clears up a spot of blight which threatened the area as well as the continued vitality of Grand avenue north of Lindell which will gain in prestige with the opening of the Symphony Society’s Powell Hall.35

The Argus clarified that “the project area is bounded by Grand Boulevard, Bell Avenue, Theresa Avenue and Delmar Blvd.,” which places Powell Hall at its southwest corner. Irvin Dagen, executive director of the St. Louis Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority (and one of the original members of the St. Louis Committee of Racial Equality), explained that “the St. Louis Symphony Society’s work in remaking the Old St. Louis Theater into Powell [Hall]…will add to the new interest and growing strength of this area.”36

A report in the previous week’s Argus, however, suggested a less rosy view of urban renewal. The Mid-City Community Congress, an activist group founded in 1966 that “promoted militant black community development and control from within the federal antipoverty bureaucracy,” objected to the Model Cities proposal that had been approved by the Board of Aldermen on January 16, protesting that “the citizens of St. Louis, who will be deeply affected by the plan have had no chance to study, discuss, or question the actual proposal.” “We question good faith in citizen participation in the plan,” wrote the MCC, “since the citizens have been virtually excluded from planning the proposal.”37 Meanwhile, as Frank Peters of the Post-Dispatch enthused, “a progress report on Powell Hall is necessarily out of date the day after it is written, for scores of workmen are busy in every part of the building…Stanley J. Goodman, the Symphony Society president and an experienced builder of department stores, is using his talents in a way that Symphony customers next year will appreciate.”38

Left unspoken in public celebrations of Powell Hall’s role in revitalizing the Grandel area was the reality that many “Symphony customers” were affluent White people who lived miles from the neighborhood. While questions about safety and comfort persisted as the St. Louis Theater became Powell Hall, those questions thus came to center on the worries of suburban visitors. An agreement with nearby parking facilities had been made by August 1966, when the executive committee was still considering whether to purchase the hall, but “Mr. [Richard K.] Weil pointed out that many people feel that the area around the St. Louis Theatre is dangerous at night and will be hesitant to walk to the theatre from the parking lot. Mr. [Alfred] Fleishman said that the neighborhood is changing for the better, and that the Police Department will co-operate in making the streets safe.”39 In April 1967, Fleishman reassured the board of directors that “he had spoken with the chief of police who assured him the area will be policed well and visibly…Mr. Fleishman stated that Powell Symphony Hall would be the safest place in town.”40 A 1967 brochure advertising the orchestra’s upcoming move to the new hall reassured patrons that “adequate, well-lighted parking facilities will be available.”41

All this talk of a changing neighborhood and “the parking problem” tip-toed around racial tension that a reporter for the Boston Globe made explicit:

Grand Boulevard was the Broadway of St. Louis 40 years ago; now it is a dispirited thoroughfare smelling of popcorn, uncomfortably midway between downtown (no longer moribund after some dreadful years) and the residential suburbs. Powell Hall is, in fact, right on the edge of St. Louis’s enormous black ghetto, and there has been some subscriber unease about it. [Managing Director Peter] Pastreich regards the location as a challenge more than a problem, and the orchestra has begun what it hopes to make an extended program of activities designed, really for the first time here, to establish some sort of relationship with the Negro community.42

Left unspoken in public celebrations of Powell Hall’s role in revitalizing the Grandel area was the reality that many “Symphony customers” were affluent White people who lived miles from the neighborhood.

The Wall Street Journal, in its review of Powell Hall, also advocated for such a relationship, explaining that “this problem is too often alluded to vaguely as the nasty situation ‘over there in that part of town’ with the high crime rate” and adding that “it doesn’t require a Black Power extremist to perceive that in cities of increasingly large black populations more active programs must be instituted to draw the Negro into the cultural mainstream, to afford a sense of participation and not to impose by omission the role of ‘invisible man.’”43 During 1968, the orchestra’s outreach to the Black community included a concert on May 12 celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Urban League of St. Louis, for which the League’s block units were given complimentary tickets.44

Figure 4: Opening night crowd in the lobby of Powell Hall, January 24, 1968. (Photo: Ralph D’Oench, Missouri Historical Society)

In covering Powell Hall’s opening, both the Globe-Democrat and the Post-Dispatch focused on the venue’s splendor rather than any concerns about its urban environs, touting “the patron’s comfort and enjoyment” as well as the elegance of the remodeled hall (“a delight for lovers of rococo opulence”; “Powell Hall has luxurious elevators deeply tufted in red plush and illuminated by crystal chandelier”).45 Readers of the Post-Dispatch might have turned the page to learn, in a separate report, that the Missouri Commission on Human Rights, in an amicus curiae brief, had just “told the Supreme Court that discriminatory policies of subdivision developers in St. Louis county have helped bring about de facto apartheid.”46 Some St. Louisans likely saw the two stories as related. The Globe-Democrat reported vaguely that at the orchestra’s Inaugural Gala Concert and Champagne Ball on January 24, 1968, “about 23 demonstrators” from an unidentified “civil rights group paraded in front of the main entrance carrying signs and chanting, but as soon as dignitaries began arriving, police moved the pickets south of the entrance. They left after the concert began.”47 The Post-Dispatch reported that “patrons were not delayed by pickets outside who bore signs such as ‘[Mayor Alfonso J.] Cervantes fiddles while St. Louis burns.’”48 The Wall Street Journal clarified that “a small group of young white and Negro demonstrators…members of the ACTION Council to Improve Opportunities for Negroes…carried signs such as ‘Sound of Music Muffles Cries of Jobless’ and distributed leaflets stamped ‘The Insensitive White Man,’” which called upon the “all-white orchestra” to hire Black musicians.49 Other signs read, “We don’t need plush seats, just a place off the streets” and “Champagne for Fat Cats—No Jobs for Blacks.”50 ACTION, which historian Clarence Lang describes as “the key local organization in the transition from ‘civil rights’ to ‘Black Power,’” staged “protests tied to a national black working-class reparations campaign.”51 The group’s previous targets had included the Gateway Arch, Southwestern Bell, McDonnell Aircraft, and the Veiled Prophet Parade, a public showcase for St. Louis’s most powerful and privileged citizens. The latter event “embodied the hegemony of governmental, business and civic interests denying Black workers a humane quality of life, either by active discrimination, indifference, or empty ‘lip-service liberalism’” for the Black radicals of ACTION.52 Powell Hall, an elite cultural institution supported by corporate wealth, no doubt evoked a similar response.

The “Requiem for Mike Brown” protest of 2014 thus engaged Powell Hall’s history in deep and provocative ways that went beyond the brief disruption of an evening of high culture. The protesters insisted on concern for Black lives in a building that, as the St. Louis Theater, had excluded African Americans. They questioned the troubled relationship between police and Black St. Louisans in a venue whose rebirth as a symphony hall hinged on the promise that police would protect its patrons from the city outside. And they carried on the tradition of protest at Powell Hall begun by ACTION by bringing their voices and signs into the hall itself. An audience stirred by the undoubted beauties of the hall and Brahms’s music perhaps was moved to reimagine whose safety mattered and who was to be comforted.