The unrestrained growth of bristly oxtongue, white clover, and bull thistle on 4004 Cook Avenue is both a reason for and the result of neglect. Several slabs of concrete provide a walkway to nowhere, dozens of cigarette butts have begun to disintegrate, while pieces of scrap metal and shards of glass continue to adorn the unkempt plot of land.

In the vernacular of private property, 4004 Cook Avenue is a “vacant lot.” It is one of the thousands of such lots in contemporary St. Louis that are located in predominately Black neighborhoods, having been demarcated as “tax delinquent lands.” Eventually, by labeling these plots of land as “delinquent,” they become the legal responsibility of the state and, in St. Louis’s case, the responsibility of the Land Reutilization Authority (LRA). As of November 2020, 4004 Cook Avenue is one of more than 6,300 properties up for sale by the LRA.

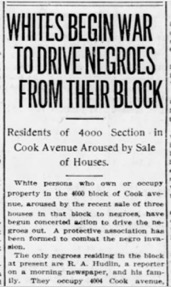

In 1912, this was the site of a “negro invasion.”¹ The White residents of Cook Avenue were faced with a predicament: three Black families purchased homes on the 4000 block that summer, including the Hudlin family, who moved in their new home on 4004 Cook Avenue that May. The system of de facto segregation that protected both property values and racial hierarchies was legally being transgressed. Soon after the summer of 1912, this action—that of a Black family moving into “White space”—would be against the law and demand the intervention of the St. Louis police.

In 1912, Mrs. May Crawford and her family purchased this home for $4,000—twelve years of saving a Pullman Railroad Porter’s salary—but it remains unclear why they never moved in.

The overgrown vegetation of 4004 Cook Avenue today is even more jarring when it is compared to what is next door: 4000 Cook Avenue, where the façade of a two-story brick residence obscures a process of slow collapse.

This was once one of the other pristine homes that a Black family purchased in 1912 on the all-White 4000 block of Cook Avenue. Cook Avenue then was in the center of the wealthy and architecturally heralded Vandeventer neighborhood in St. Louis, characterized by luxurious houses, expansive yards, and styled gardens. In 1912, Mrs. May Crawford and her family purchased this home for $4,000—twelve years of saving a Pullman Railroad Porter’s salary—but it remains unclear whether they ever moved in.² White neighbors formed a “protective association” in 1912 because their property values had “declined by 60% because of the sales to negroes.” ³

It is unclear whether in 1912 anyone ever moved into the now dilapidated  house at 4000 Cook Avenue. Bullet holes began appearing in the shed behind the house. The night Richard Hudlin and his family moved to Cook Avenue, “a bombardment” of “stones” flew at their windows. When riot police were called to the neighborhood, they ended up arresting only one man: Robert Watson, a Black man, who was patrolling the street with a revolver in hand, prepared to defend these homes against White vigilante terror. While after that night—the story of an armed Black was picked up by newspapers throughout the country in the following days—the St. Louis police department made an effort to protect these homes, municipal politicians quickly enacted racial zoning laws. A committee of White officials called for the “Legal Segregation of Negroes in St. Louis.”⁴

house at 4000 Cook Avenue. Bullet holes began appearing in the shed behind the house. The night Richard Hudlin and his family moved to Cook Avenue, “a bombardment” of “stones” flew at their windows. When riot police were called to the neighborhood, they ended up arresting only one man: Robert Watson, a Black man, who was patrolling the street with a revolver in hand, prepared to defend these homes against White vigilante terror. While after that night—the story of an armed Black was picked up by newspapers throughout the country in the following days—the St. Louis police department made an effort to protect these homes, municipal politicians quickly enacted racial zoning laws. A committee of White officials called for the “Legal Segregation of Negroes in St. Louis.”⁴

The Hudlins’ new neighbors quickly formed a “protective neighborhood association” as a “war” for the block began. With the intent of preventing more “negroes,” upper-class White citizens began organizing their political might to protect the property value, and thus, the racial make-up of their neighborhoods.⁵ This sits in stark contrast to contemporary realities: today, more than 90 percent of residents in this neighborhood are Black.⁶ What were once properties so valued that they warranted a nightly police presence, now are in gradual decay. The sanctioned neglect of properties on Cook Avenue—which today purportedly warrant a different kind of police presence—is racial at its core.

• • •

If the exposed wood beams and shattered glass on Cook Avenue could speak or—more prudently—if Black life in St. Louis in the twentieth century is examined through Cook Avenue, a story of what David Harvey and Ruth Wilson Gilmore call “organized abandonment” would need to be told. Informed by the work of Christina Sharpe, I am interested in considering the climate of racial life through Cook Avenue as a site of anti-Black extraction and racialized space. Echoing the methodology of anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, I am interested in how these properties, as my objects of observation, reveal the nature of my object of study: racial transgressions. Cook Avenue serves as a site where Black families once violated the legal, economic, and social rules of spatial existence.

In naming the “organized abandonment” of Black life that I argue such racial transgressions reveal, I am especially concerned with how abandonment is organized by and through the state. In the so-called shift from de facto to de jure segregation, as scholars like N.D.B. Connolly have revealed, limbs of the state have played consistent but obscured roles. In St. Louis, this is potentially best evidenced by the police. On Cook Avenue in 1912, the police officers who began protecting the Hudlin residence each night were, in turn, simultaneously protecting White homeowners’ property values. A century later, it is the St. Louis police that is tasked with auctioning off plots of land, previously owned by Black families, to the highest bidder. Urban histories of cities in the Midwest, like Detroit and Chicago, have increasingly called attention to the role of the state’s police power in facilitating housing segregation. It has been not just the formal policing of Black people but the constant threat of state violence in response to everyday conduct that has protected racial hierarchy in twentieth-century America.

The propertied landscape of St. Louis since 1912 is where what George Lipsitz called “the possessive investment in Whiteness” is coupled with what Frank Wilderson describes as the parasitic nature of White-ness and the state. As an empty lot and a home in slow collapse might indicate, in racially-marked neighborhoods, investments in Whiteness. Yet these material and social investments, I argue, are contingent upon a filial tie between anti-Black ideology and the state. If the state breathes, anti-Blackness is caught in each breath.

The historical terms of segregation cannot be fully captured by terms like de facto and de jure. At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, the very nature of Whiteness and Blackness had everything to do with spoken and unspoken rules of who belonged where. “Modern segregation” is a precise framework when modernity is understood as a particular story of who did—or could do—what to whom, where, when, and why. What Wilderson calls a “grammar of suffering” underlies the stories that can be told of how anti-Blackness substantiates American social life. Saidiya Hartman has explained that “the social rights of the white race depended upon segregation.” The afterlife of slavery was manifest in “the social,” which ostensibly “was beyond the reach of the state” but in reality was “an arena of collusive, contradictory, and clandestine practices between the state and its purported other, the private.”

Urban histories of cities in the Midwest, like Detroit and Chicago, have increasingly called attention to the role of the state’s police power in facilitating housing segregation.

Who could lay claim to the privacy of their own home? Who knew what it was to own, and who lived in the shadow of being owned?

Thus, the way that segregation operates reflects the nature of anti-Blackness, the significance of private property, and the climate in which racial existence thrives. For the three Black families who legally purchased homes on Cook Avenue in 1912 and for Robert Watson who legally had the right to carry a firearm publicly, they did not transgress codified law. But it would take only five years for racial ordinances their actions inspired to be drafted, put up for a vote, passed, and taken to the Supreme Court.⁷

In reflecting on Cook Avenue in 1912 and today, I am in turn reflecting on how racial transgressions operate beyond the frameworks of de jure and de facto segregation. The contemporary house in slow collapse and the adjacent vacant lot are not just material sites; they are sites where the actions of people instigated new iterations of racialized state power. These two properties were once important to the state and important to the families who wished to move in. This shared significance is what these two sites of observations might allow us to study.

The challenge of trying to consider transgressions, especially when they are documented as brief episodes or as fleeting events, is that we must rely on fragmented archives to make sense of them. Indeed, to make a point of naming the two Black families and their circumstances is to claim some type of knowledge or understanding of their lives. But the names and other information about the people who purchased homes on Cook Avenue are scarcely documented, and newspaper accounts—the foremost source of knowledge about the events in 1912—only provide information about two of the families.

“Modern segregation” is a precise framework when modernity is understood as a particular story of who did—or could do—what to whom, where, when, and why.

What took place in May 1912 and what has unfolded since then is unclear. Indeed, a caveat to my argument is that I am relying on glimpses, snippets, and slivers of lives: the full landscape of peoples’ lives are not just obscured but made impossible to unearth using traditional historical sources. The vacant lot is accompanied by the emptied archive. It is not a futile pursuit, but it is one we should carefully consider. Finding Black life in the archives is a tenuous task. As scholars like Saidiya Hartman have shown, the lives of Black women are fractured and disfigured by conventional modes of reading historical texts. Moreover, the violence of the archive begins from the moment of its creation, assembly, and codification. In the context of state archives, the question becomes: who and what is deemed necessary to provide an official account of the past. Archival research is not futile. It does not have to be a scientific task of finding the concrete truths of history. Instead, there are modes of engaging with the past that surface the very conditions that obscured those lives in the first place. The objective is a series of encounters with all the past has to offer and, with that, with what the official archive makes it hard to see.

Thus, an incomplete story begins. The story starts before Richard A. “R.A.” Hudlin moved to 4004 Cook Avenue with his wife—whom archival materials scarcely mention—and their sons Richard II and Edward. The Hudlin family was deeply rooted in Black life in St. Louis. The Hudlins traced their lineage back to Owen Lovejoy’s Underground Railroad stop in the city. In 1869, the Kirkwood School District opened up a temporary building for Black children and their first Black teacher was Richard. The next year, he was appointed principal. When the Hudlins moved into their new home, Richard had become a reporter and publisher for The American Eagle, a morning newspaper.⁸

Hudlin had worked a number of jobs in the St. Louis area. In 1890, he was nominated to be the postmaster of the city of Clayton in 1890 by President William McKinley, which typically meant automatic approval by Congress. Just four days later his nomination was rescinded.⁹

The paradigm of “separate but equal” was readily applied in private workplace contexts in order to deny Black citizens the substantiation of their legal rights, yet Hudlin was being denied a federal position. No explanation was provided—at least in writing—but there were de facto signifiers at the time that made clear that Black postmasters were not wanted, especially outside of entirely Black communities. In the 1880s and 1890s there were few Black postmasters working outside of small cities in the South, and one of those postmasters—Frazier Baker—had faced a campaign to force his removal from that position. Subsequently, he and his daughter were lynched.10 Hudlin, determined, sought nomination again, received it, and served as the postmaster for several years.11

R.A. Hudlin’s professional life was not just characterized by breaking new ground. He took on platforms from which he might not only resist Black people’s status as second-class citizens but actively take to task the promises of legal equality under the law.12 Thus the act of moving into the all-White Vandeventer neighborhood was not out of character for the Hudlin family: without using legal means, Richard’s professional career often tested the boundaries of what “separate but equal” meant in reality. The night that the Hudlins moved in, however, introduced a new set of consequences, brought about by their violation of a racialized physical space.

The night that the Hudlins moved in, their home was attacked by their neighbors. “A gang of white boys” had come by and “bombarded the house with stones…several windows were broken.”13 When the police arrived they found Robert Watson, a Black private detective, patrolling the streets. The officers arrested Watson for carrying a concealed weapon. The night ended; it is unclear whether any protection was provided to the Hudlin family, which was still susceptible to harm.

The contemporary house in slow collapse and the adjacent vacant lot are not just material sites; they are sites where the actions of people instigated new iterations of racialized state power.

The slippage of the archives does not reveal what happened next: newspaper accounts reported that riot police had arrived, implying a scene or altercation taking place at 4004 Cook Avenue, but when the night ended only the “negro” involved was arrested. It begs the question of who in the neighborhood called the police and for what reason? When the Hudlins and two other Black families had purchased this home, a White citizenry had grown angry. Who was this gang of White boys—presumably teenagers, presumably impressionable youth? Yet, at the same time, in order to “combat negro invasion,” a White neighborhood coalition had already been formed.

So what would that group of people have made of the armed Black man patrolling the street? How else were the Hudlins to keep themselves secure, at the very least for that first night? For the Hudlins defending themselves involved a particular form of protection: armed self-defense. For White citizens, whether they contacted the police or not, historically their protection had been and would be provided by the police and, in turn, through legal and political means, by the state.

When The Crisis reported on 4000 Cook Avenue, they placed it alongside other racial transgressions that dealt not only with prejudice but the nature of the state. In their “color line” update, they wrote:

A majority of Southern cities achieve separation of White and Negro passengers in street cars by assigning them to different seats, or by the use of movable screen partitions. Montgomery, Ala., stands alone in unqualifiedly requiring separate cars for Whites and Negroes. North Carolina forbids White and Negro passengers occupying contiguous seats on the same bench. Virginia prohibits their sitting side by side unless all the other seats are filled…. it is generally found that conductors have police power to eject or arrest willfully disobedient or refractory passengers, and in some few cities police on the cars are required to take cognizance of any violation of the law…. Efforts to bar colored residents are reported in sections of Washington and in St. Louis. From St. Louis it is reported that the first Negro moved to Cook Avenue lately, taking possession of 4004 Cook Avenue. That night the house was bombarded….When the police were summoned they arrested Robert Watson.…on the charge of carrying concealed weapons…. The house at 4000 Cook Avenue has also been bought by a colored woman Mrs. May Crawford….4008 Cook has been bought by Mrs. Sadie Lyle, another colored woman….These have not yet moved in.14

In some ways, the examples given of streetcar segregation anticipate the story of Cook Avenue. Streetcar segregation at the time was being actively made legal by the extension of Black Codes that had evolved into Jim Crow laws. Meanwhile, what R.A. Hudlin, May Crawford, and Sadie Lyle had done was completely legal—they had purchased homes. In 1912, their behaviors were not against the law. But these examples are deeply similar. The expanded ability of the police to “eject or arrest the willfully disobedien[t]” has some relationship to the arrest of Robert Watson. This arrest seems to have had everything to do with the legal movement of a Black family into a White neighborhood. The lines of what is de jure and what is de facto are readily blurred.

After the night rocks were thrown through their window, more rocks came. The shed in the back of R.A. Hudlin’s house was lit aflame—again and again. The abuse became so routine and persistent that a deal was struck with the city. Police officers would be assigned to guard over the Hudlins’ home at night, on the city’s bill. Five police officers watched the property from May until October. As this agreement unfolded in the summer of 1912, it garnered more news than the initial abuses. Multiple Black publications noted that the city was spending “$15” or “$16” a day to guard “his home from possible attack by Whites who resent what they term a ‘negro invasion.’” One publication posited that a “negro’s rest is costly.”15

Why did the city of St. Louis pay to protect this Black family? Again, the archive does not make it clear. The benevolence of a single police official? A city performing a true commitment to their Black citizens’ well-being? These are possibilities. Yet, they are possibilities against a particular backdrop. The archive does give insights into the environment in which the decision was made—it delivers a clear backdrop to what else was taking place, to the moving pieces.

The shed in the back of R.A. Hudlin’s house was lit aflame—again and again. The abuse became so routine and persistent that a deal was struck with the city

A week after rocks were initially thrown at R.A. Hudlin’s home, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch announced that the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange had created a Race Segregation Committee. An article followed that mentioned racial zoning policies and appeared clearly connected.16 The Exchange began investigating other cities’ segregation policies, trying to ascertain how growing Black populations in urban areas might be managed. St. Louis was a viable destination on the front end of the Great Migration, a development which lawmakers from the Midwest had been making note of since the 1880s, and city officials were ready to take matters into their own hands. As municipal officials heard the complaints of White homeowners whose home values decreased when people of color moved into their neighbors, “separate but equal” became a rationale through which subjugation could be justified. Housing laws that imposed “Black spatial isolation” became a strategy through which the state could protect White communities. Simultaneously, local segregation laws allowed Black communities to be left unserved.

In December of 1912 the St. Louis Exchange proposed an ordinance, modeled after a similar law in Baltimore, which would “provide that where the majority of persons in a block are Whites, negroes will not be permit-ted to come in, likewise Whites will be barred from the blocks of which the majority of residents are negroes.” Lawmakers touted the ordinance explaining that “in Baltimore and Richmond where similar ordinances are in force, the records show that there are twenty violations by White per-sons to only seven by negroes. This plainly indicates to me that the negroes as a race do not resent the plan.”17

Swiftly, in the 1910s and 1920s, local lawmakers worked to make housing segregation the law. While police officers guarded the Hudlin home, lawmakers worked to enshrine inequality in the name of a racial order. Over the next four years, the city of St. Louis would become a hotbed for housing ordinances and practices of segregation based on race. What Garrett Power has called “Apartheid Baltimore Style” was the beginning of an evolution of homeownership policies that revolved around protecting the sanctity of White life and divesting material resources from Black communities.

The myth that over the course of the twentieth century the state, namely through federal legislation, has dismantled the infrastructures of “old racism” reflects a misunderstanding of how legal power operates. In 2020, for instance, the house in slow collapse at 4008 Cook Avenue has a “delinquent” legal status: nowhere is it indicated that it exists in the shadow of racialized degradation by design. Yet the apparatus of legalized violence was made by the state at the beginning of the twentieth century, when an arrangement of harms and exclusions began tearing away at notions of Black citizenship. A pile of amassed debris is the material relic of where Sadie Lyle and her family planned to live their lives. Today, it is recognized by the state as a site of neglect. In 1912 and 2022, however, the question is: who recognizes Cook Avenue as a deliberate site of legal neglect? How do we account for neglect that is facilitated by the police power of the state?

In attending to the archive, we have no idea if Lyle and her family ever moved in, and this is not the story of what has transpired there, particularly in the decades since. Instead, our knowledge can only revolve around what is missing; it requires considering the slow, fast, and ongoing processes of state violence. In the arc of the twentieth century, we know that what Sarah Haley terms “Jim Crow modernity” does not leave us. And now 4004 Cook Avenue is in a neighborhood that is overwhelmingly Black, disproportionately impacted by the criminal legal system, whose public schools have struggled with accreditation, and where children struggle to breathe. Racial inequality is apparent, and it is everywhere.

But like the streetcars in 1912, which could be segregated by the force of a police officer or the streetcar driver—an empowered citizen—the state can create spaces that are uninhabitable.

If we are to locate sites where the state, as Christina Sharpe explains, “registers and produces the conventions of antiBlackness in the present and into the future,” we must attend to the house caving in on itself. It might be a story of foreclosure. It might be a story of a storm. But today, when this part of Cook Avenue is predominantly Black, it is inevitably a story of the climate. The anti-Black weather that undergirds the legal infrastructure of abandonment constitutes how Black people in St. Louis experience the state—whether it is an interaction with the mayor, with the police department, or at the local DMV.

As municipal officials heard the complaints of White homeowners whose home values decreased when people of color moved into their neighbors, “separate but equal” became a rationale through which subjugation could be justified.

As contemporary material sites, 4004 and 4008 Cook Avenue reflect how spaces become marked by race: the worth of a given plot of land becomes overdetermined by history. Emma Coleman Jordan, in her analysis of the subprime mortgage crisis—where 51 percent of subprime refinancing took place in predominately Black neighborhoods—contends that the twenty-first-century crisis “began with a systematic set of circumstances in which some people had houses and land and some people did not.”

As various forms of oppression manifested through the twentieth century, the absence of wealth in Black communities has consistently been maintained. This is the story of racial capitalism that is most evident in a historical process like White flight but is just as much at play in the criminalization of poverty and brutal repression of Black resistance. The various economic transformations in the twentieth-century United States consistently left Black people disproportionately jobless, incarcerated, without secure housing, and poor.

This is made clear nowhere more than in terms of owning valued homes: the transgressive act that made Cook Avenue a site of contestation. Today, White households have on average more than $111,000 worth of wealth compared to just over $7,000 for Black households. We would be remiss to ignore the circumstances in which this gap was created, in which the state allowed these gaps to emerge and persist. Scholarship increasingly points to homeownership as the main factor in how the racial wealth gap in America has been maintained across the century, while other metrics have changed.

Whether or not they violate de facto or de jure rules, Black citizens throughout the twentieth century have been restricted in their ability to “move well,” economically and through space.18 And so, when returning to where—from the perspective of Cook Avenue—this story begins, it is a climate that characterizes the transgressions that occur. As the legalization of these restrictions burgeoned in the early twentieth century, the character of de facto segregation was installed.

In 1914, a new city charter was passed that provided the Real Estate Commission with more power. In 1916, the city placed a zoning ordinance on the ballot that drew restrictive lines around the “negro blocks,” lines that would have forced the Hudlin family to move, would have ensured the Crawford family and the Lyle family never moved in, and more broadly ingrained segregation in the city. That ordinance and similar laws elsewhere were struck down by the Supreme Court.

In 1923, using a vote by its members, the Real Estate Commission left three Black neighborhoods as unrestricted zones for real estate transactions, while labeling White neighborhoods as worthy of investment and improvement—those neighborhoods that were endorsed were those that had been “devising methods to prevent invasion by negroes.” In the 1930s, the Homeowners Loan Corporation would use the language of “invaded” or “infiltrated” to describe (and define) neighborhoods where Black people lived and that investors should avoid.

A pile of amassed debris is the material relic of where Sadie Lyle and her family planned to live their lives. Today, it is recognized by the state as a site of neglect. In 1912 and 2022, however, the question is: who recognizes Cook Avenue as a deliberate site of legal neglect?

What has become described as an urban crisis, the unveiling of American apartheid, was the unveiling of how racial subjugation in the twentieth century had come to operate. When W.E.B. Du Bois argued that the twentieth century would be the century of the “color-line” he emphasized that relationality stating “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races.”

It is why St. Louis, born from transgressions on Cook Avenue that threatened the value of White properties, would develop in the segregated fashion so visible today.

In revisiting the second site—that of the vacant lot—all that is not there and all that has been abandoned is on display. These, however, are not just spatial concerns. The emptiness reflects a type of divestment; a broader set of abandoning practices of the state. For more than seventy years, members of the Hudlin family lived at 4004 Cook Avenue. They saw the neighborhood transform, they saw the city change and simultaneously stay the same.19 And, likewise, the nature of racial transgressions have an unbroken past—evident in the Hudlin family. R.A. Hudlin’s son, who saw the shed behind his home lit aflame again and again by his neighbors before the police intervened, would go on to be the first Black captain of a Big Ten conference tennis team at the University of Chicago. As a high school teacher, he would successfully sue the city to ensure that regardless of race, any student could participate in municipal tennis events in St. Louis.

His son was the first Black chief circuit judge in Illinois. His niece Pelagie Wren was the first Black dancer to perform at the Muny. His great-great nephews are the Hollywood famous “Hudlin Brothers.”20

The Hudlin family, the residents of the home once occupying this now abandoned lot, time and time again faced de facto restrictions and de jure rules. They consistently broke new ground but remained in a set of racial relations that surrounded them.21

The Land Reutilization Authority’s current ownership of 4004 and 4008 Cook Avenue is a reminder of this racial relationality. The Land Reutilization Authority was created in 1971 in part because of a growing number of abandoned and vacant lots—driven largely by White flight, foreclosed homes, and the general deindustrialization of the city. It is the oldest land bank in the country. Less-known is that the Reutilization Authority is not the first line of defense for “tax-delinquent” or unused properties. Before they are acquired by municipal authorities, these properties are given to the sheriff. The sheriff, and the legal arm of the state, in turn, is tasked with holding an auction before the Reutilization Authority gains access. Indeed, the state and the law enforcement of the state are able to grab land and sell it to the highest bidder. As the St. Louis metropolitan area has received increased attention because of its law enforcement, its municipal tax systems, and its treatment of Black citizens, how is this a tolerable state of affairs? Is it just the nature of the times, just inherent to the wind—a facet of living we should accept as the climate?

We are in the midst of it. An ideology of the state that draws no real lines between de jure and de facto segregation, but instead creates holding patterns wherein anti-Blackness is the convention. How else should we understand 4000 Cook Avenue? Police officers arrested Robert Watson for armed resistance, armed defense of supposedly private property. Only after his property was bombarded with rocks did R.A. Hudlin receive protection from the state for his home. And only when the state was actively making the law that they could not live there, did the police protect the Hudlins. Only when sheriffs are those who profit off of abandoned lots, dying neighborhoods, and homes in slow collapse can we see and feel the nature of the state.

Theorists of the state, such as Timothy Mitchell, contend that the state’s most dubious effect is implying that the state is separate from the ideologies that enable “the people.” Claims made to the state, the story goes, will be responded to if they are made by the state’s constituents. But this fictitious rendering of the state conceals the nature of the state’s investments. When the state is built upon and in service of White proper-tied interest—one could argue—a transgression involving a Black citizen is presumed to be a transgression by a Black person against “the people.” The world, as arranged, is anti-Black. The climate is projected as natural, inevitable, and the status quo. Our laws, our practices, and our living are presented through premises—life, liberty, property, equality, and wealth—which in the modern world are reliant on this mode of subjugation.

The Hudlin family, the residents of the home once occupying this now abandoned lot, time and time again faced de facto restrictions and de jure rules. They consistently broke new ground but remained in a set of racial relations that surrounded them.

Anti-Blackness is in the air. There lies another story in how the Hudlin family lived in that home for decades. And yet another story of Black social life that cannot be discovered through official state archives. A story unfolding in the midst of a storm.