I. “THOU SHALL NOT COVET”

On a sunny February morning in 2016, three St. Louis police officers escorted Larry Chapman and Gustavo Rendon from a grassy lot at the 2300 block of Mullanphy on the near side of North St. Louis. While devoid of buildings, the lot at the heart of the St. Louis Place neighborhood was well-tended, and filled with items brought there by residents, including a picnic table, a barbeque grill, lawn chairs, and a trash can. On this particular morning, the lot also contained a wooden crèche with a dark-skinned, blanketed “Jesus,” several candles, a set of solar-powered lights, a large green tent, and a plastic-sheathed copy of a papal encyclical on the human rights of laborers, Rerum Novarum (1891). When police arrived on the scene, Rendon was holding a sign that read “THIS HOME IS NOT FOR SALE,” and Chapman was standing in front of a large chalkboard-green billboard featuring a passage from the King James Bible:

THEY SHALL BEAT THEIR SWORDS INTO PLOUGH-SHARES, AND THEIR SPEARS INTO PRUNING HOOKS…NOR SHALL THEY TRAIN FOR WAR (IS. 2) | NO EMINENT DOMAIN | NO NGA.

Members of the press snapped photos as the police hauled off the billboard and handcuffed Chapman and Rendon, who were active in a group called Save NorthSide STL, several of whose members lived a stone’s throw from the site. The group had been vocal in its opposition to redevelopment of the area, especially as the city began its long courtship of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which sought a large tract of land for its new midwestern headquarters.¹

Residents had good reason to be nervous: the city’s Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority (LCRA) had already begun property maneuvers in the area—months before the NGA officially announced its intentions to build a high-security compound on a 99-acre tract that included the 2300 block of Mullanphy.² As of the first of February 2016, the NGA’s long-awaited decision still had not been delivered, and Chap-man and Rendon, along with Rendon’s wife, Sheila, launched a “prayer action” and hunger strike on the site to protest what increasingly seemed a fait accompli: the loss of their homes. Sleeping on the site in a tent, they also sent letters to federal officials, spoke to local media, and placed hand-painted signs around the neighborhood. One in the Rendons’ yard, which was located across the street from the site, admonished city officials: “YOU SHALL | NOT COVET | YOUR NEIGHBOR’S HOUSE.”

These acts of political opposition were confidently and prayerfully asserted, rooted in claims of rightful ownership and decades of stewardship and care for their beloved neighborhood. Their actions contrasted sharply with the abuses of the state and the self-interested machinations of city officials and private developers. This essay considers the deeper contexts of the campaign of resistance at the site, laden as it is with political, moral, and symbolic power, in order to assess the neighborhood’s position in the material world of segregation in St. Louis. In so doing, it uncovers what Walter Hood calls the “prophetic significance [of ] emancipation heritage” that is often contained in the “vernacular black landscape”—the everyday sites of Black residence and community, many of them contested, devalued, and ultimately erased. In such sites, Hood reminds us, one often finds not only “traces of memory and guilt” but of “resilience, faith, optimism, and invention,”³ and the grassy lot at 23rd and Mullanphy is no exception. Like St. Louis Place as a whole—a neighborhood so beleaguered and yet so beloved—the site manifests many characteristics that can also be found in other predominantly Black neighborhoods across the St. Louis region, from the Ville to Howard-Evans Place to Kinloch, each of which has been subjected to threats from those who would seek to extract their value and expunge their negative associations. At this particular site, the negative and positive have become fatefully entangled, and yet residents have found ways to express its emancipation-heritage significance.

An initial glimpse of that significance can be found in the residents’ selection of the verse from Exodus. In the months leading up to their prayer action, the Tenth Commandment had been something of a mantra for those who had been resisting the incursions of development in their neighborhood over some fifteen years. They often held up signs bearing the verse at public hearings about the NGA, and echoed its sentiments when speaking to the press, asserting again and again: “THIS NEIGHBORHOOD IS NOT FOR SALE.”⁴ For Chapman and the Rendons, the verse served as a guiding premise for their activism—a faith-rooted invocation of God’s justice. In Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo XVIII references the commandments in an argument that the State should not “act against natural justice” when intervening on matters of private property. He goes on to offer a broader endorsement of the rights of laborers to organize, whether through unions or mutual aid societies, and thus to resist abuses of state or corporate power.⁵ When viewed in this light, the verse has distinct moral and symbolic potency—particularly when posted on a grassy lot that once was home to a church named for the self-same Pope. St. Leo’s Catholic Church, built in 1888 (Fig. 2), was a major community asset for nearly a century—and remained so even after the building was no longer there. On and off since its demolition in 1978, and especially in the last two decades, the site has served as an informal gathering place and a locus of community activism.

An initial glimpse of that significance can be found in the residents’ selection of the verse from Exodus. In the months leading up to their prayer action, the Tenth Commandment had been something of a mantra for those who had been resisting the incursions of development in their neighborhood over some fifteen years.

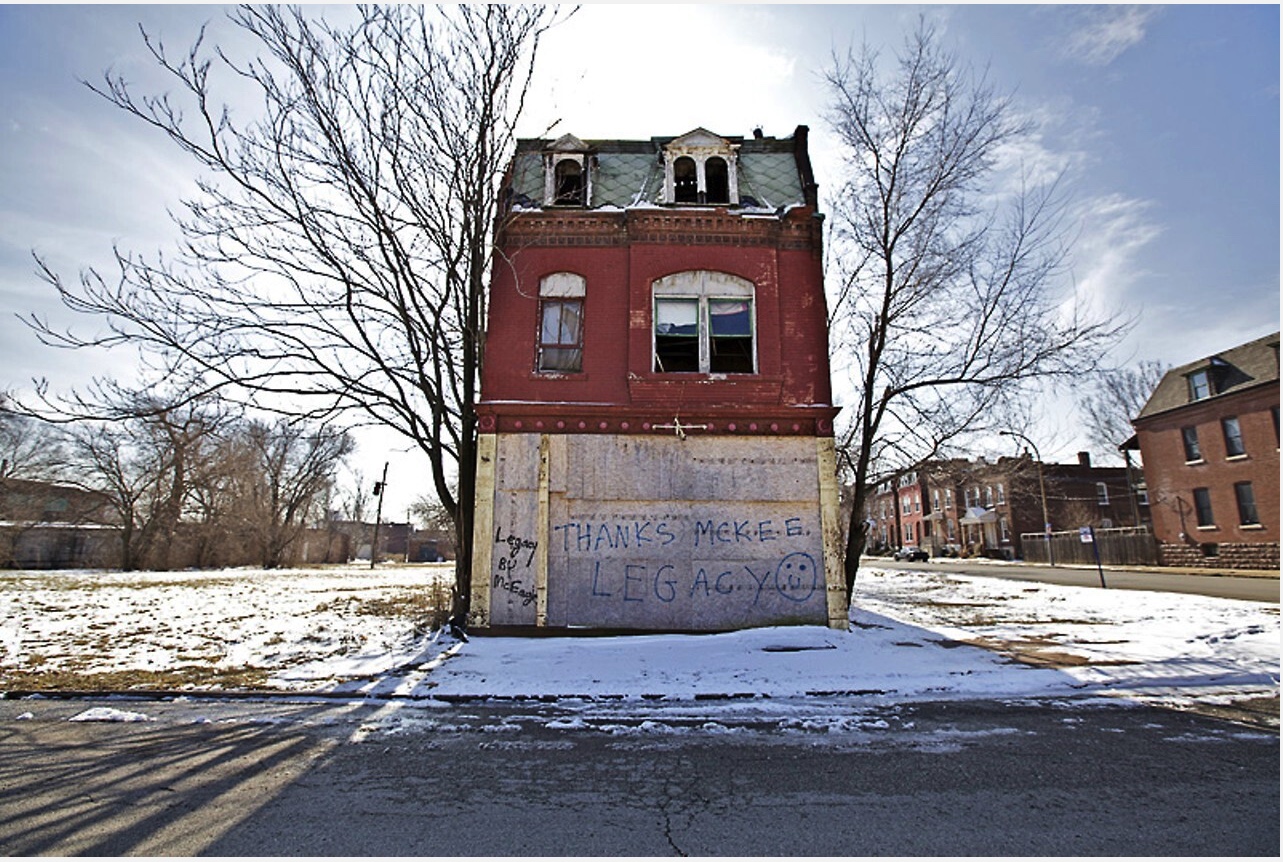

The decision to stage a prayer action at St. Leo’s was not a function just of convenience or sentimental attachment, however. Like so much apparently-but-not-properly-vacant land in the area, the lot was owned by suburban real estate tycoon Paul McKee, who began purchasing declining or abandoned properties across North St. Louis in 2003, and who, by early 2016, had acquired some 2,000 parcels between Grand and Martin Luther King Boulevards, North Florissant Avenue, and Highway 40, including the long-abandoned Pruitt-Igoe site nearby, and some 65 percent of the putative NGA tract. It was McKee who had called the police that morning when he spotted the protestors while driving the neighborhood in his SUV, and McKee who filed charges against them. And it was McKee who had become the special target of residents’ animus—ever since they learned of his secret purchase of huge swaths of land over more than a decade. Anti-McKee graffiti could still be found on vacant buildings across the area, much of it making ironic reference to his reneged promises to salvage “legacy” (historic) properties (Fig. 1) on the land.

Figure 1: Anti-McKee graffiti on a house at North Market and North 20th in 2010. (Jennifer Silverberg, Riverfront Times)

McKee was clearly the intended audience of the “THOU SHALL NOT COVET” message—but not the only one. As the protestors well knew, Congressman William Lacy Clay Jr., (D-St. Louis) had invited members of the press and his colleague Adam Schiff (D-Calif) to join him and McKee for a tour of the hundred-acre district under consideration by the NGA that same day, during which the developer would lay out his “North Side Regeneration” vision. This only confirmed residents’ suspicions that the two projects had become entwined, and that McKee was part of an elaborate behind-the-scenes deal-cutting that involved Mayor Francis Slay, and the state’s then two U.S. Senators, Roy Blunt, Jr. (Rep.) and Claire McCaskill (Dem.). While the congresspeople declined to meet with Save Northside STL protestors that day, Clay took time to counter their arguments against the NGA, telling them: “If you think there’s something left to salvage” in this neighborhood, “shame on you. You don’t know what winning looks like.…”⁶ But the protestors’ actions nevertheless served to remind the politicians involved, and the broader public, that this seemingly “vacant” section of North St. Louis was not, properly speaking, vacated—that St. Louis Place, including its empty lots, was still lovingly tended by residents who had no intention of selling their homes.⁷

Staging those actions at St. Leo’s made sense for other reasons, both historical and symbolic. The pretty gothic-revival church (Fig. 2), which cost $40,000 to build, had been dedicated on the site in 1889, during the Jubilee of Pope Leo XVIII. Some five thousand people attended the cornerstone-laying ceremony, and dignitaries who paraded through a neighborhood festooned with papal colors noted the dynamism and growth of the district with surprise. A school and temperance hall were soon built alongside (both run by the Sisters of St. Joseph), and for ninety years, St. Leo’s served a vibrant working-class parish, its population a mix of native-born and immigrant, poor and middle-class, laborers and merchants. Many of its parishioners were Irish, but German immigrants also had a strong presence in the area during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when they constituted about half of St. Louis Place’s residents and were active in social and political organizations. Their influence can still be seen in the distinctive brickwork on surviving “legacy” buildings in the area, which helped to secure the National Historic District status of St. Louis Place in 2011.⁸ (McKee has repeatedly vowed to save as many of these as possible.)

The German and Irish were soon joined, and eventually replaced, by Eastern European and Jewish immigrants, as well as migrant laborers from the American south. Many African Americans who struggled to find housing elsewhere in the city due to cost, landlord bias, and restrictive covenants settled in the neighborhood, or in nearby Mill Creek Valley, the Ville, and DeSoto-Carr, and they generally stayed long after thousands of White residents relocated. Between 1970 and 1988, St. Louis Place lost 1,200 housing units and saw its population drop from 12,000 to 2,500. In 2017, many of its 100 remaining residents were second- or third-generation Black home-owners for whom St. Leo’s—even in its absence—was part of neighborhood as well as family memory, a place of shared kinship and collective heritage, and the site of an annual reunion of families who remained and some who moved away. Among other things, the site evoked this longer history of progressive social and political action—the kind that drew much of its strength, and some of its inspiration, from the community’s religious beliefs.

Figure 2: Historical photograph of St. Leo’s, date unknown. (Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Archives and Records)

II. A Landscape of Disorder + Disruption

The distinctive emancipation heritage of St. Louis Place is rooted also in a long history of contestation and material disorder, much of it associated with a century of urban renewal. When first established, the neighborhood sat alongside one of the city’s most reviled slums, the so-called Kerry Patch, whose western edge was a few blocks east of St. Leo’s. By the 1880s the area had evolved from a shantytown built by desperately poor (and often detested) Irish into a “colony of squatters” who held land between Seventeenth and Twentieth Streets.⁹ A notoriously squalid district said to be over-run by drunkards and petty criminals, and thus “unpoliceable,” the Patch was periodically visited by muckraking journalists, who wrote colorfully of its decrepitude and corruption but also its slum mystique.10 While few spoke of the longer history of the area, once the core of the “Union Addition” of 1850 and before that, part of the city’s common field system (in which subsistence farming, collective grazing and timbering occurred), the material traces of these public-use functions remained, compounding the Patch’s negative associations for late nineteenth-century observers.11 Acreage that previously contained a quarry and sewer collect, for instance, had with time, become sloughs of “every kind of filth” imaginable, including ashes, manure, offal from local butcher shops, and carcasses of dead pets—all of it “festering and…contaminat[ing] the air for blocks around,” as one nearby resident put it in 1895.12 Most of the homes in the area lacked indoor plumbing, which resulted in the pile-up of waste in alleys and vacant lots. These conditions, which were harshly critiqued in a housing study published by the Civic League in 1905, were not fully ameliorated until the second half of the twentieth century. And they appear to have persisted even longer as trace elements of place memory, resurfacing in the form of blight-related anxieties and, more recently, in the denigrating descriptions of abandonment.

Figure 3: The remnants of DeSoto-Carr in the middle of this long period of disruption (looking South from Carr toward Pruitt-Igoe; St. Leo’s is a few blocks west), c. 1955. (Missouri Historical Society)

But this was not the whole story, since the Union Addition saw substantial speculative building starting after the Civil War, and St. Louis Place eventually became “the largest cohesively developed subdivision in north St. Louis,” a fashionable streetcar suburb anchored by an elaborately landscaped “pleasure park” (established in 1865, and developed in phases over three decades) featuring showcase mansions, mostly built by German industrialists, and more modest middle- and working-class flats and single-family homes, as well as some small-scale industry.13 While no doubt fueled by anti-immigrant bigotry, much of the hysteria over conditions in the Patch was a function of economic self-interest and, in particular, the desire, by absentee landholders and middle-class homeowners especially, to see the area once and for all purged of the “filth” which hampered their pursuit of bourgeois urbanism. In their view, the poor residents in the area, especially the squatters, were agents of moral, material, and social-economic disorder. Many were direct descendants of those whom the Mullanphys—an influential Irish landholding family after whom the street was named—had allowed to live in the Patch rent-free since the late 1840s, and continued to assert ownership rights for decades after the establishment of St. Louis Place.14 It was not until Mullanphy heirs went to court in 1899 that long-time “squatters” were finally expelled, at which point the city promptly razed gardens, animal pens, and cottages (some reportedly thatched in the “old Irish style”) on the land and converted it into taxable parcels for residential development.15 But the Patch never quite resolved, in the spatial sense, and the area experienced uneven development in the decades that followed.

The distinctive emancipation heritage of St. Louis Place is rooted also in a long history of contestation and material disorder, much of it associated with a century of urban renewal.

These legacies of unruly materiality and contestation continued, as the city pursued multiple campaigns of renewal-related clearance that only further destabilized St. Louis Place and its environs. The demolition of St. Leo’s (1978) signaled not the end of an era, but another inflection point in half a century of disturbance of mostly Black neighborhoods in the immediate area, among them DeSoto-Carr (Fig. 3), where clearance paved the way for a series of public housing experiments built with federal subsidies, including Carr Square (1942), Cochran Gardens (1952), and the sprawling, ill-fated Pruitt-Igoe (1954).16 Mill Creek Valley, a 79-block, 57,000-unit district just a half-mile south of St. Louis Place—home to 20,000 middle- and working-class African Americans, and dozens of celebrated cultural, religious, and educational institutions—was demolished starting in 1959 to make way for the Daniel Boone expressway and the “St. Louis of tomorrow.”17 Like the long-time habitants of the Kerry Patch, the displaced residents of Mill Creek Valley and Desoto-Carr had no political recourse and few affordable housing options. Those who qualified for public housing moved into Pruitt-Igoe, while others bought or rented in St. Louis Place, JeffVanderLou, the Ville, and other aging North St. Louis neighborhoods. Many found themselves in a state of perennial housing insecurity, bedeviled not only by redlining and racist landlording but also, once they managed to buy homes, by intentional disinvestment in, and maligning of, their neighborhoods.

These legacies of unruly materiality and contestation continued, as the city pursued multiple campaigns of renewal-related clearance that only further destabilized St. Louis Place and its environs.

The cumulative effects of all the “slum surgeries” (the medical trope favored by mid-twentieth-century advocates of “radical amputation” of “creeping blight” in working-class neighborhoods) and periods of “benign neglect” can readily be seen today. Aerial photographs of St. Louis Place and its environs taken around this time showed the rapidly disappearing street grid and small smattering of residential and commercial structures, now enclosed by grassy lots like the one at St. Leo’s and even cornfields. Between 1970 and 1988, the neighborhood lost 1,200 additional housing units and saw its population drop from 12,000 to just 2,500. The trend continued, and intensified, such that by 2016, only fifty residents remained (part of the reason the site seemed eminently viable for redevelopment).18 Some of these came from families that had been displaced by renewal two, three, even four times since the 1950s, and some whose parents or grandparents had been first-generation Black homeowners when they bought into the neighborhood. These few were steadfast in their commitment to the area, despite deterioration on all sides; many of them asserted the heritage significance of St. Louis Place as they fought against the NGA project, as when lifelong resident Charlsetta Taylor, who submitted a petition with 90,000 signatures in opposition to eminent domain, asserted: “Our homes are our heritage. They represent the lives of our fathers and grandfathers, [and their] struggle to become part of this nation, to own land…” Sheila Rendon likewise viewed her home on Mullanphy, which her parents purchased in 1963 when the neighborhood was still well-populated and St. Leo’s and Pruitt-Igoe both stood, as “part of their American dream,” celebrating the “house pride,” which she and others have so loudly asserted in the face of McKee’s buyout.19

III. “THIS HOME IS NOT FOR SALE”

For decades, these St. Louis Place residents maintained their homes while fighting for basic services, like trash pickup and streetlight repair and working to hold McKee accountable to his promises. But as more properties owned by the developer, or held by the Land Reutilization Authority (LRA), collapsed, many due to brick thievery and arson or neglect, the city evaded their inquiries, and the LRA refused to consider their offers to purchase abandoned properties in the neighborhood. St. Louis’s longest-serving major, Francis Slay, eventually joined McKee in his assessment that total rebuilding—or what Rep. Clay called a “project of scale”—was the only viable option for the area. Community activists in turn called out McKee and the city as agents of neglect, and even conspirators in a decades-long plot to transfer land to “real estate investors and speculators” of the kind Andrew Herscher has documented in Detroit.20 They also continued to resist dismissive characterizations of their neighborhood as urban wasteland. In Exodus (2016), a documentary made by filmmaker Jun Bae in collaboration with homeowners facing the looming threat of eminent domain, one longtime resident describes the common view of St. Louis Place in this way:

People say it’s not a neighborhood because there’s not a house on every block. But it is a neighborhood, because there are people here. They’re my neighbors. And they been here, waitin’…holdin’ onto the land. And that’s the American dream, right? To own your home…To you it may seem like we live in the ghetto, [a] desolate wasteland, but we live in a neighborhood…21

Yet the “desolate wasteland” view—first expressed by detractors of the Patch, and later codified in Harland Bartholomew’s influential “blight” studies and served up to the media by developers and even local aldermen—nonetheless dominates public discourse. Indeed, McKee’s plan has been predicated upon it, as has been the NGA’s project; both partake of the self-justifying logic of “demolition urbanism,” which conflates abandonment and vacancy with deterioration and depopulation and overlooks chronic housing issues exacerbated by the city, not to mention the legacy of racist housing policies.22

But for residents facing up to these forces, the corner of Mullanphy and 23rd was neither abandoned nor deteriorating. It was, as Chapman and the Rendons often noted, a sacred space23—one whose violation, if no more grotesque than the kind repeatedly endured by Black residents in North St. Louis, had special portent given its status as a place of religious gathering. Indeed, St. Leo’s continued to anchor communal rituals of worship, with its own liturgical calendar; the church’s original stone altar and candle-stand, which sat on the western edge of the lot alongside a homemade creche hung with white or purple bunting and a hammered-metal crucifix (Fig. 4) salvaged from another historic North St. Louis church, were the locus of all manner of prayer actions, not all of them aimed at the public. Residents brought candles, incense and other tokens, and planted flowers at the base of the altar, whose inscription, at once mournful and accusatory, reads “BEHOLD THE TABERNACLE OF GOD AND MAN.” These were small-scale acts of devotion and community self-care that gave expression perhaps to anticipatory grief, but also to grim determination: “THIS HOUSE [of worship] IS NOT FOR SALE.”

… the “desolate wasteland” view—first expressed by detractors of the Patch, and later codified in Harland Bartholomew’s influential “blight” studies and served up to the media by developers and even local aldermen—dominates public discourse.

Such acts should also be seen as forms of resistance to the logic of eminent domain—and to the legacies of abuse and abandonment across African-American St. Louis. On this, one of thousands of parcels held by McKee, residents asserted a specific right not just to the property, but also to other elements of the vernacular landscape that, while they were legally someone else’s property, nonetheless represented communal heritage. If, like Jesus and his followers, they had become aliens in their own land, they had also followed his command to beat swords into ploughshares; to cultivate the ground no one else wanted, and pursue “congregation” in the midst of segregation, “fashioning ferocious attachments to place as a means of producing useful mechanisms of solidarity.”24 The focus of this ferocious attachment was St. Leo’s, as Gustavo Rendon noted in 2017: “We’ve been taking care of this property for a long time…mowing, picking up trash, maintaining things [McKee] doesn’t.”25

Figure 4: An Exodus film still showing St. Leo’s in 2017, with a homemade creche of purple bunting and a hammered-metal crucifix.

These attachments extended beyond St. Leo’s and backyards, encompassing vacant lots some residents turned to urban gardens and small-scale farms. A few involved formal lease agreements with McKee or the city, but many involved extra-legal use. Sheila Rendon notes that, after repeated futile attempts to purchase property from the LRA, she and Gustavo planted a garden on land adjacent to their house and cared for it determinedly. Such actions represent a modified commons principle of the kind practiced in colonial St. Louis26 and the Kerry Patch, or what today is often called “squatters rights,” whereby those who tend and care for a piece of land, who depend upon it for their well-being, assert an alternative ownership claim rooted in care-giving and productive use. St. Louis Place residents had not only asserted such claims over decades, but creatively expressed their rights to do so through occupation of St. Leo’s, perhaps inspired by statement 8 of Rerum Novarum:

God has granted the earth to mankind in general, not in the sense that all without distinction can deal with it as they like, but rather that…the limits of private possession have been left to be fixed by man’s own industry…the earth…ceases not thereby to minister to the needs of all, inasmuch as there is not one who does not sustain life from what the land produces.…27

The “limits of private possession” had been dramatically manifest in the material and political history of St. Louis Place and environs, places so ravaged by urban renewal, strategic neglect and absenteeism that even the most modestly scaled acts of “industry”—mowing and planting flowers, cleaning up trash, tending parks, keeping homes in good repair—could properly be understood as stewardship.

IV. “St. Louis Wins!”

The NGA’s long-expected decision finally became public about a month after Chapman and the Rendons started their prayer action.28 The agency released an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) of the North St. Louis site on April 1, 2016, and its formal Record of Decision (ROD) to build the headquarters there a few months later, after a period of “public comment” that did little to slow the process of securing the remaining properties, the Rendons’ house among them. The EIS confirmed what officials had been saying for years: that the large polygon of “predominantly vacant land” on the Northside was beyond salvage and ready for “reclamation.”29 The rationale for such reclamation was laid out in the ROD. Like colonial settlers and nineteenth-century industrialists, the NGA saw many advantages in the site, including a stable bedrock core, proximity to city government and educational institutions (especially the city’s “Tech Corridor”), ease of access to highways, and proximate cultural amenities. The site had one other major advantage: priority status under federal law. In 2015, Obama designated North St. Louis (along with neighboring Normandy, Jennings, Wellston, and Ferguson) as a Promise Zone, which encourages cross-agency collaboration on economic development in high-poverty areas.30

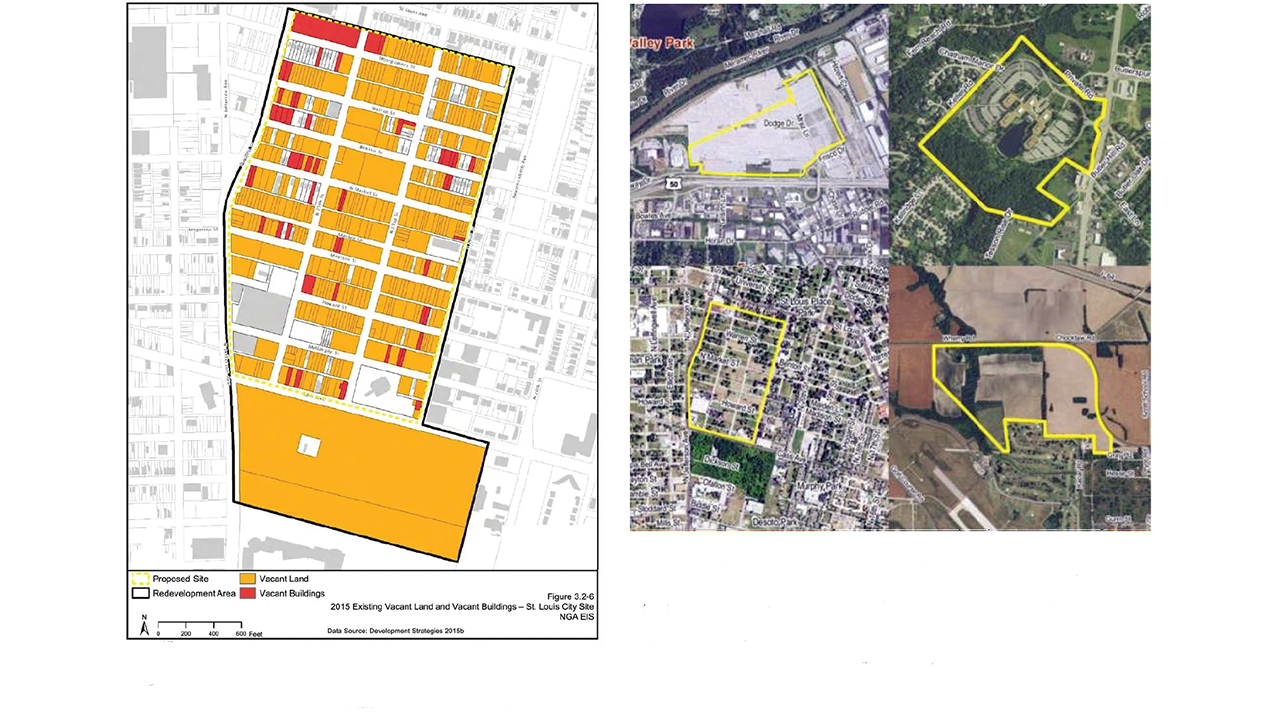

The images embedded in the ROD, and later, in the archaeological study mandated by federal law, much like the aerial photos commonly included in media coverage of Northside Regeneration, seemed to confirm the “blighted” status of the land, and the need for the radical intervention—no longer a “radical amputation,” but instead, a complete “visual transformation” of the area—that the agency and its backers promised.31 For city officials and business leaders, the promise of visual and economic transformation in this “long-suffering community” was a central preoccupation—a matter of political and even psychic urgency with almost existential significance for some. Officials longed for redevelopment of any kind, even the farfetched proposal by McKee, because they saw it as the means by which ghosts of the past—in particular, the urban planning and social policy failures that had ravaged the African-American community—could finally be exorcised. At times, it seemed all of these ghosts resided in a large green rectangle at the south end of the NGA redevelopment zone: the thirty-four-acre urban forest where the towers of Pruitt-Igoe once stood. Here, alongside decades of litter and abandoned furniture, were a handful of artifacts from the city’s most humiliating experiment with public housing, as well as rubble from other building projects that have harmed communities of color. Like the Kerry Patch, the Pruitt-Igoe site had become a literal and figurative dumping ground whose shameful associations had not diminished with time, and whose rectification was keenly desired.

Figure 5, left: “Existing Vacant Land and Vacant Buildings” (NGA’s Environmental Impact Statement, 2015). Figure 6, right: Aerial maps of the NGA’s four finalist sites: former Chrysler plant in Fenton (top left), Tesson Ferry Road (top right), North St. Louis site (bottom left), and St. Clair County site on farmland adjacent to Scott Air Force Base (bottom right) (NGA’s Environmental Impact Statement , 2015).32

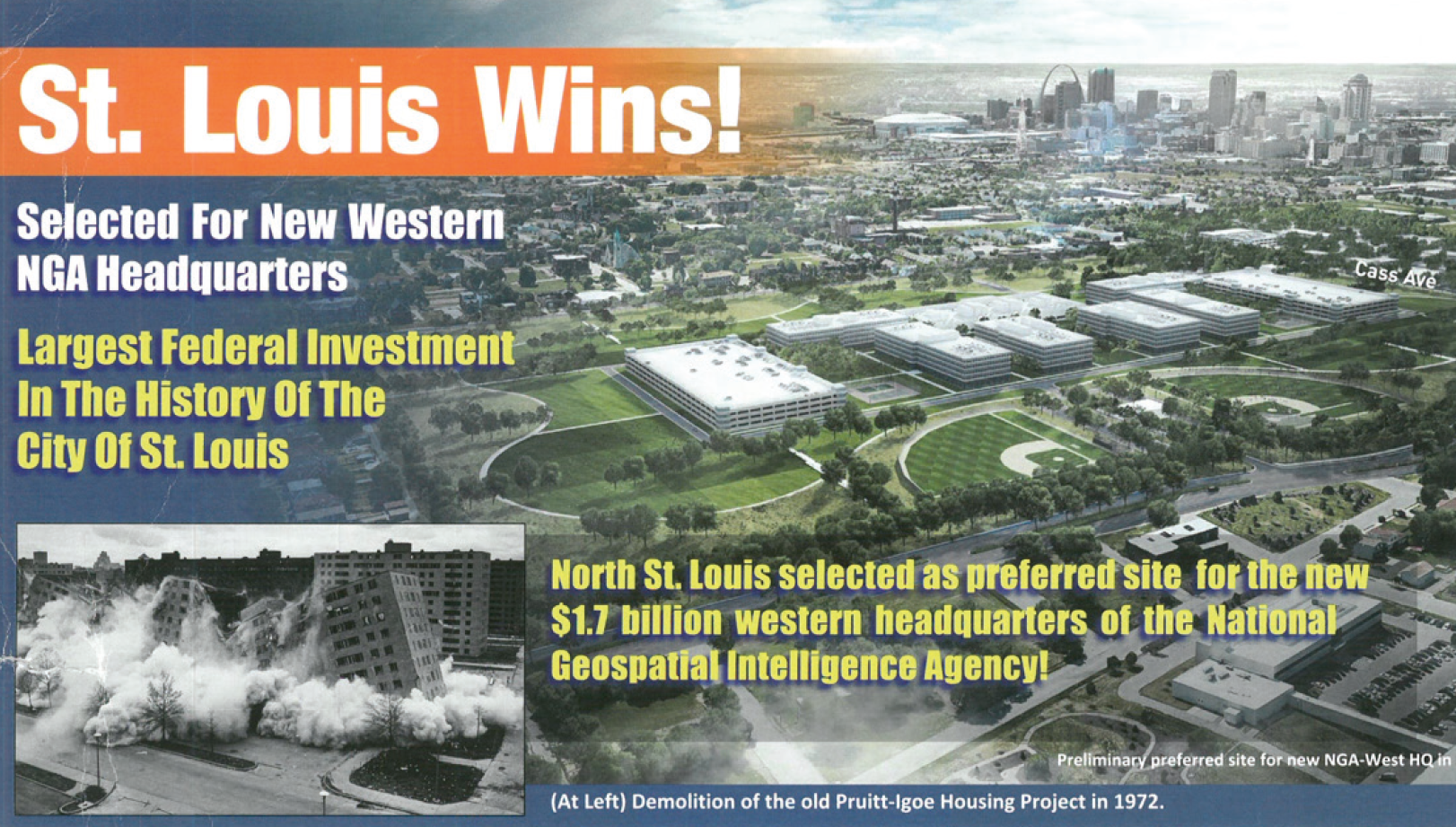

Public officials were so fixated on the unredeemed site, in fact, that the broader area under consideration by the NGA came to be referred to simply as “Pruitt-Igoe,”33 a rhetorical slippage that continued even after it was understood that the latter would likely be excluded from project. If the conflation was for some a function of spatial confusion or wishful thinking, for others it was a self-conscious compensatory strategy—good planning making up for bad; selective and humane “rehabilitation” rather than abusive “renewal” or total demolition; the righting of past wrongs—that had first been advanced by officials back in 2014, as when then-Mayor Slay’s chief-of-staff contended that choosing St. Louis for the $1.75 billion NGA facility would be a “very elegant” way for the federal government to “[undo] injustice created many decades ago.”34

Perhaps the most unabashed expression of this logic came from then Rep. Clay, who has repeatedly claimed that the “rejuvenation” of North St. Louis will make up for the harms of the “federal disaster” known as Pruitt-Igoe.35 In June 2016, he sent a mailer (Fig. 7) to constituents celebrating the NGA’s decision to build in St. Louis, the front of which was dominated by a full-color architect’s rendering of the headquarters with a sweeping view of downtown and the Arch, and framed by a bold headline: “St. Louis Wins!” If readers failed to understand just what kind of vindication this represented, a thumbnail version of the infamous Pruitt-Igoe implosion photograph made things clear.36 A month later, the Post-Dispatch ran an article about the sale of Pruitt-Igoe to McKee that juxtaposed the same implosion photo with present-day images and a map of the conjoined NGA/NorthSide sites.37 For his part, McKee had already embraced this compensatory logic, and within weeks of the NGA’s announcement, had reframed NorthSide Regeneration as a “large-scale and holistic” mixed-used redevelopment plan and “home of the next NGA West Campus.”

Officials longed for redevelopment of any kind, even the farfetched proposed by McKee, because they saw it as the means by which ghosts of the past—in particular, the urban planning and social policy failures that had ravaged the African-American community—could finally be exorcised.

This compensatory logic could not, however, clear away what geographer Tim Edensor calls the “surplus materiality” of the area’s history—not only the physical traces of the past, but its “overlooked people, places and processes,” which had again been thrust into view.38 In the case of the Pruitt-Igoe site acquired by McKee, surplus materiality was comprised of literal rubble that eventually would be cleared, but also psychological and symbolic excesses that could not quite be contained by all the “St. Louis Wins!” talk.39 To obsessively conjure up the imploding, excessive Pruitt-Igoe in discussions of the new NGA headquarters was not only to associate the latter with planning failures past, but to disclose unsettling resemblances between then and now, between the spectacle of demolition and the work of so-called regeneration, and between one set of radical interventionary measures and another. It was also to call to public mind the long sub-merged material history of the area—one which would be physically laid bare in the months to come, as archaeologists documented the contents of local privies dating to the 1850s (uncovering porcelain teapots and spittoons, ink bottles, clothespins, a child’s teething ring and rattle, and countless other artifacts), and again when bulldozers tore into the homes of St. Louis Place residents, and obliterated Mullanphy and 23rd as well as other beloved landmarks, including a modest cinderblock church known as Grace Baptist, which had served Pruitt-Igoe residents, and continued to minister to the needy on the Northside ever since.

Figure 7: The front of the June 2016 mailer sent to residents in then-Rep. Clay’s district (MO-1st). (Author’s collection)

On April 1, 2016, the day that St. Louis’s “big win” finally became official, residents’ hunger strike came to a painful conclusion, and residents gathered at the St. Leo’s site to pray. This moment of collective grief—which reporters were on hand to document—must also have been an act of defiance, rooted in decades of political congregation and resistance at the site. Here again, as through countless acts of caretaking and incarnational presence, residents countered ongoing defamation and abuse, and showed that St. Louis Place was the inverse of an urban wasteland—that it was in fact a celebrated piece of emancipation heritage, where not just “traces of memory and guilt,” but also of “resilience, faith, optimism, and invention” were powerfully manifest.

The prayer gatherings would continue at St. Leo’s—even once the NGA erected a fence to keep them out—and most of the displaced residents would relocate to nearby houses in what remained of St. Louis Place or other Northside neighborhoods. The Rendons would “rebuild what they had lost,” and “make [the neighborhood] beautiful again,” rehabbing a derelict house (one of the same vintage as their old home) less than a half-mile away, just outside the NGA footprint.40