In November 2020, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran a feature article on a one-mile section of the city’s North Grand Boulevard that is the deadliest in terms of murders. This stretch includes the eastern edge of Fairground Park, a historic landscape on which adjacent neighborhoods rely for recreation, congregation, sports, and fishing. Accompanying the article online was a short video showing how an outdoor roller rink in the park’s northeast corner has become a “beacon of hope” in the sometimes violent area.¹ The video shows the lively, joyous world of the rink, which attracts mostly Black skaters. The skaters enjoy embodied freedom—a right to the city that is as much individual as collective. This right, in this park, represents a recent and rare historic victory, as Fairground Park offers a longer record of White suppression of Black rights to public space.

Just six years prior, for instance, then Chief of Police Sam Dotson elected to place barricades at the park’s vehicular entrances to block the flow of young Black motorists on a beautiful Sunday in May.² Dotson wanted to prevent access for “cruising,” where young people drive around to see and be seen by their peers, in the center of the park. The activity was causing disruptive congestion and inspiring altercations, according to the police chief. Then Alderman Antonio French (D-21), whose ward included the park, cried foul, reminding the police that his parents had participated in cruising in the park when they were younger. Residents of the area around the park, which demographically is almost all Black, also pushed back on Dotson’s decision.³ French publicly wondered whether such an extreme control over free movement in a public park would occur in other neighborhoods, insinuating that Dotson’s decision might be racialized.⁴ Dotson did himself little favor when he withdrew the barricade plan for future weekends, stating that “[b]locking it meant the good people couldn’t get into the park, either.”⁵

The rules of public space in St. Louis have remained inconsistent, often informal, but also usually enforced by the police power of the local state.

The barricade episode displays a recurrent affront to Black citizenship in St. Louis specifically and the United States generally: criminalization of embodied presence through the targeting of recreational use of public spaces ostensibly free and open to all. While St. Louis’s history of systemic apartheid of real estate has been well-documented, the legacy of denial of equal rights to public spaces is far less known, perhaps because St. Louis was not a strict Jim Crow city. The rules of public space in St. Louis have remained inconsistent, often informal, but also usually enforced by the police power of the local state.

The rights of Black St. Louisans to the city’s parks technically have never been denied by law, but the exercise of those rights has rendered many Black people criminal through police targeting and arrest, or through informal measures such as removal of certain recreational features (the basketball hoops removed from Lafayette Square in 1996) or supposedly colorblind by racially-motivated restrictions on use (such as the city’s picnic licenses for O’Fallon Park, enacted in 1922 after White complaints over Black picnics). As Robin D.G. Kelley writes: “Those targeted by the state are not rights-bearing individuals but criminals poised to violate the law who thus require vigilant watch—not unlike prisoners.”⁶ That watch today can take forms as diverse as Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson’s decision to kill Michael Brown for jaywalking, or the countless “Karen” and “Ken” White vigilante enforcers and harassers who show up at pool parties, ice cream shops, and parking lots to dilute the citizenship of non-White Americans.

Figure 1: White families enjoying recreation at Fairground Park. Source: St. Louis Public Library Collection.

At Fairground Park, however, the most spectacular instance of organized denial of the rights of free use for Black St. Louisans remains the riot caused by White people when the city opened the park’s swimming pool to Black swimmers in 1949. This episode grounds the later barricades as a sort of musical coda, extending the violence inflicted when the park anchored a historically White settlement in transition into the period when the settlement was almost exclusively Black. In the interregnum, Black St. Louisans won the battle for equal possession of real estate—and made the neighborhoods around the park into vibrant, safe places to live. But it turns out that the rights of using Fairground Park were unresolved as recently as six years ago.

At Fairground Park, however, the most spectacular instance of organized denial of the rights of free use for Black St. Louisans remains the riot caused by White people when the city opened the park’s swimming pool to Black swimmers in 1949.

Fairground Park itself was the product of expansive, state-sanctioned, racialized gentrification of North St. Louis through the platting of street-car suburbs. The Agriculture and Mechanical Fair had used the eastern end of the park from 1856 through 1902, and at its cessation the Jockey Club and horse race track remained a popular attraction. The Zoological Garden occupied a site at the southeast corner of the park as another vestige of the fair. The almost bucolic site jarred with developers’ steady suburbanization of the O’Fallon neighborhood, with plats to the west and north beginning as early as 1859 and home building increasing after 1890. Suburban developers, including City Council ent John Gundlach, who resided just north of the park in one of his own developments, pressed the city to acquire the land for development as a public park.

The development of public parks after the mid-nineteenth century was central to making cities healthier, prettier and more profitable—as well as an opportunity to expand the policing of Black people through the expansion of regulated public spaces. Figures like Gundlach envisioned democracy as a White project, and the promises of public landscapes as equally restricted endeavors. The North St. Louis Business Men’s Association made the case for the amenity: “Here were 131 acres of wooded parkland in the most accessible location in St. Louis. Aside from a few tennis courts and baseball fields in O’Fallon, Carondelet and Forest Parks, the City had no playground, i.e. of outstanding character. … No similar tract of park for playground purposes of approximate size and availability was to be had.”⁷

Figure 2: Aerial view of Fairground Park as it appeared sometime between 1930 and 1939. Source: Missouri History Museum Collections.

In 1909, the city dedicated the site as Fairground Park, after acquiring the land in the previous year. Landscape architect George Kessler designed formal interventions including the construction of an ornamental lake, building of recreational fields, and the planting of trees in a romantic landscape manner. In 1913, a massive public swimming pool (perhaps the largest in the nation) opened in the park—the first in a northern state to be formally restricted to Whites.⁸ While parks were never formally segregated in St. Louis, park amenities began to be segregated in the early 1900s as the Black population began increasing.

The pool’s segregation fit the agenda of Gundlach—one of the founders of the American Planning Association and a political liberal from the emergent upper middle class—to build a protected enclave where Black and poor people would be excluded. Exclusion of poor White people was affected simply through the high rent prices of dwellings, but exclusion of Black people—which included a burgeoning middle class—required soft police power. The developers took aim at an area just west of Fairground Park, where a Black community rose up in the space behind the race track stables—benighted land “on the wrong side” that now was desirable and high-value with a new park improvement. As developers replatted the area, they used covenants to ensure that at least new occupants would not be Black.

The 1910 platting of Fairground Place, advertised as a middle-class subdivision, restricted nonresidential uses, mandated houses of at least two stories costing at least $3,000 to build and stipulated that “the property hereby conveyed shall never be sold conveyed, leased or rented to or occupied by negroes.”⁹ Houses across the street had Black residents, creating an instant conflict over the street.10 Similar tools were used in Lucille’s Fairground Addition, where 1912 restrictions included a $4,000 minimum cost, 40-foot building line, minimum height of one and a half stories, and proscribed “Negro” owners or residents. By this instrument, the lots were subject to forfeiture if the conditions were not observed.

At the time the 1916 segregation ordinance was passed, the Post-Dispatch published a map showing the districts in St. Louis that met the 75 percent threshold.11 Four of the districts were pulled out and shown in detailed insets: Mill Creek Valley, The Ville, Arlington Grove, and the smallest area, four full and four partial blocks, immediately west of Fairground Park. The settlement impeded the realtors’ vision of White middle-class settlement in O’Fallon, anchored by O’Fallon and Fairground parks. Ironically, the suspension of the zoning ordinance, after the United States Supreme Court ruled in 1917 through Buchanan v. Warley that Louisville’s segregation ordinance—prohibiting the sale of certain real estate to African-Americans violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution—made this area more vulnerable.

Exclusion of poor White people was affected simply through the high rent prices of dwellings, but exclusion of Black people—which included a burgeoning middle class—required soft police power.

After 1917, realtors and developers implemented restrictive covenants in the Fairground Park area that dispossessed Black St. Louisans from further settlement, while the ordinance gave long-term settlement state sanction. Despite the mechanism of property law to enforce apartheid, the open access to public parks began posing a racial threat to the White order in the area soon after the Supreme Court ruling. When Black St. Louisans began taking weekend streetcar rides to picnic in O’Fallon Park, just north of Fairground Park, Gundlach and other political leaders succeeded by 1922 in forcing Mayor Henry Kiel to order “picnic licenses” just for that park, allowing White officials to curtail Black access and perpetuate a pre-text for more policing of their mobility.12

Few reported conflicts over space occurred around the O’Fallon neighborhood until after World War II. The systems of covenants and the Real Estate Exchange boundary maintained the geography as sanctioned White territory, and the conflicts over use of the parks never resumed. Civil rights activism in St. Louis through the Depression and World War II focused on labor equity and electoral clout instead of urban spatial freedom. A citywide population drop in 1930 suggested that spatial conflict might not be as dire as before, but stasis would not be achieved. Between 1940 and 1950, 38,000 Black residents moved into the city of St. Louis.13 In 1930, a City Plan Commission survey had located 80 percent of the city’s Black population within the Real Estate Exchange boundary.14 However, this land proved inadequate for new residents, and already was overcrowded in many parts of the Mill CreekValley and DeSoto-Carr, conditions condemned as blight by the city’s 1947 Comprehensive Plan.

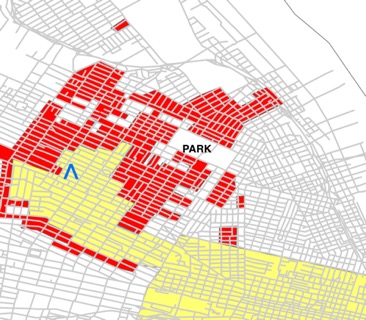

Figure 4: By 1941, Fairground Park was surrounded by restrictive covenants and close to the Metropolitan Real Estate Exchange unrestricted area. Source: Colin Gordon map annotated by the author to note the park location.

In 1941, the Real Estate Exchange expanded the boundary to reach west of Grand Avenue to encompass a larger part of The Ville area. This new boundary lay within five blocks of Fairground Park, suggesting that the White middle-class enclave around the park might be in the path of potential racial integration. Although the Exchange simply was ceding this land, not trying to make the Great Migration influx easier for the city to absorb, its members were not averse to the profitability of selling houses to Black buyers. In many ways, the Exchange boundary constituted a market price control, and its expansion instantly depreciated real estate so that purchasers—often realtors themselves—could buy low and then sell high to Black buyers constrained by the boundary. Restrictive covenant com-pacts surrounded the new boundary close to Fairground Park as White homeowners resisted integration.15 Again, the conflict over real property was just part of the territorial battle looming for White racists—public space was also at stake. The expanse of Black population in north city meant that Fairground Park was now the closest large public park with major athletic facilities to many Black St. Louisans.

The old Black enclave west of Fairground Park had persisted through 1930, although restrictive covenants now governed the entire area south of Kossuth Avenue and north of Natural Bridge Avenue by 1945. Census and deed records show that five houses on the 4200 block of Sacramento Avenue were occupied and owned by Black families in 1930. In 1938, Dunbar School kindergarten teacher Grace M. Gordon purchased a lot on the south side of San Francisco Avenue for the purpose of building a church for Black families. The O’Fallon Park Protective Association held a protest meeting at Bowman Methodist Church that attracted a large crowd of White dissidents intent on preventing the sale.16

When Black St. Louisans began taking weekend streetcar rides to picnic in O’Fallon Park, just north of Fairground Park, Gundlach and other political leaders succeeded by 1922 in forcing Mayor Henry Kiel to order “picnic licenses” just for that park, allowing White officials to curtail Black access and perpetuate a pretext for more policing of their mobility.

On the 4100 block of Harris Avenue, Black families lived in five houses built by White speculators in 1908. However, these families were gone by the end of World War II, suggesting that covenants effectively policed properties as they were vacated or sold, and that White residents remained invested in the old project of erasing Black population there. After the Buchanan decision, developers often blanketed areas like this one with covenants and homeowners associations to protect property values. However, as Colin Gordon notes, the piecing together of juridical exclusion tools almost exclusively occurred in extant or developing White areas as a defensive strategy against Black “invasion.”17 The project in O’Fallon may have been the city’s first dispossession program, ahead of later exercises of mass condemnation on Black neighborhoods, gradualist as it was.

Although Fairground Park would have seemed to have achieved total segregation by 1949, in fact it became a landscape of anxiety. The advance of Black settlement and a general decline in housing values made the surrounding O’Fallon neighborhood less of a certainty and more of a possible turning point. In fact, the police reported White violence against Black families that had managed to purchase houses north of Fairground Park in weeks leading up to the pool opening.18 The O’Fallon Park Protective Association stated that the Shelley v. Kraemer decision was “a decided impetus to the trend of Negros moving into what, up to that time, had been White neighborhoods.”19 The Association remained so enflamed that it even was one of two neighborhood organizations to submit amicus curiae briefs in support of restrictive covenants in the 1953 Supreme Court case Barrows et al. v. Jackson, in which the Court affirmed the Shelley v. Kraemer decision.

White residents may well have been on edge as their bastion seemed poised to integrate. The pool at the park came first, although true to the pattern of city government, through neither law nor transparent action. Instead, Parks Commissioner Palmer Baumes inquired to Director of Public Welfare John J. O’Toole whether the city had any law supporting the administrative segregation of swimming facilities, and stated that the question arose each year. After initially asking Baumes to make the decision, O’Toole finally decided to allow integration.20 In fact, O’Toole, a loyalist to Mayor Joseph Darst and political insider, actually issued a denunciation of the understood extra-legal restrictions that maintained the White order. O’Toole told a reporter: “I can’t lawfully refuse them. I’m not going to be a party to an unlawful gentlemen’s agreement. I can’t oppose anyone lawfully using a swimming pool. They are taxpayers and citizens, too.”21 However, O’Toole and Baumes never directly communicated the decision to the Police Department or the Mayor.22 After suburban Webster Groves barred Black swimmers from the city pool on June 19, reporters asked City of St. Louis officials if they would follow suit. Pool staff received scant direction, rendering the decision less of a mandate.23

Figure 5: Black and white children at the Fairground Park pool on June 21, 1949. Source: State Historical Society of Missouri.

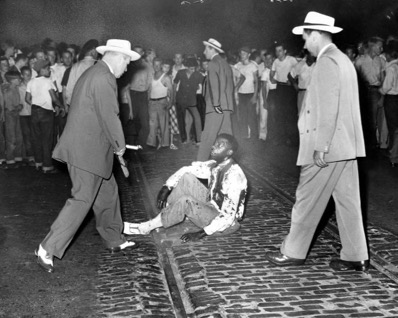

On June 21, early tensions escalated after 200 White children and teenagers surrounded and began attacking 30 Black children who had entered the pool. The ensuing events led to the congregation of some 5,000 people in the park, including Cardinals fans who walked over from Sportsman’s Park to join the mob. The White mob not only attacked Black swimmers and visitors to the park, but ventured into surrounding areas to attack Black pedestrians and at least one streetcar rider.24 Even the press called the groups of White boys who roved around the park chasing Black teenagers and children “gangs.”25 Over 400 police officers, with 51 vehicles, attempted to break up a riot that lasted all night and spilled out of the park landscape. Incidents of White-perpetrated violence against Black people ranged across north and central city according to news reports. The Police Department later proudly noted that officers refrained from using tear gas on the violent mob, an irony that has deepened with every tear gas canister used by the same department on peaceful civil rights demonstrations in recent years.

Figure 6: Bloody and beaten, a man sits in Kossuth Avenue interrogated by police detectives during the riot. Source: St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In the end, five Black people and one White person were seriously injured, although police arrested three White people and four Black people. Meanwhile, at no other city pool, including the other outdoor facility at Marquette Park in a nearly all-White area in south St. Louis, did any violence occur. However, none of the other pools was situated in an area where an all-White regime of public access and property ownership stood poised to fall. Natural Bridge Road, the park’s southern boundary adjacent to the pool, was no longer a bulwark against Black migration.26 Mayor Darst immediately closed both Fairground and Marquette Pools on June 22, 1949, opining that while the Parks Commissioner had correctly read that segregation was not established in law, he had breached a “community policy” that allowed harmony through segregation.27 Darst proposed a new pool in the Black Mill Creek Valley as a possible solution, willfully ignoring the actual geography of Black settlement and endorsing continuing to abridge the rights of use of public facilities. The annual report of the Parks Department for 1949 does not even mention the incident, perhaps indicating the mayor’s drive to conceal the incident and its effect from official record.

The project in O’Fallon may have been the city’s first dispossession program, ahead of later exercises of mass condemnation on Black neighborhoods, gradualist as it was.

Darst did soon establish a fifteen-member Council on Human Relations to investigate how to improve racial relations in the city. When the Council convened in July, it elected White insurance executive Henry F. Chadeyne as chairman and Black high school educator C.E. Broussard as vice chairman, and quickly hired George Schermer, the Director of the Mayor’s Interracial Committee in Detroit, to investigate the pool riot and make a report on its causes, effects, and remedies. Interest in reconciliation after the pool riot could be negatively measured in the rising for-sale listings of dwellings around Fairground Park in the summer and fall of 1949. White families fled, and Black families moved in—creating an uneasy integration that would prove temporary.

Meanwhile, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People held an event in which Daniel Byrd of its New Orleans office called for re-opening the pools as integrated places, stating that the “eyes of the nation” were now on Mayor Darst.28 White moderates represented by the local League of Women Voters chapter called the White instigators of the pool riot “hoodlums,” asked the mayor to reopen the pool, but also suggested that staggering segregated and non-segregated swimming hours might soften the sting of integration.29 Three conservative Missouri state senators used the event to justify blocking a bill integrating the state university system.

The contradictions manifest in St. Louis by the occurrence of the pool riot in 1949 were dryly noted by Schermer in his eventual report, The Fairgrounds Park Incident ( July 1949). Schermer’s analysis of the causes of the riot was not explicitly spatial, but made inferential statements that conflated the Jim Crow geography of St. Louis and its juridical structures. Noting that most Black St. Louisans “live in a narrow, congested area running from the river westward to Kingshighway,” Schermer summarized that the walls of St. Louis were both visible and invisible.30 While Missouri’s Constitution mandated segregated schools, it also allowed for change.

Roman Catholic schools were integrated. Motion picture theaters, restaurants, hotels, and churches were segregated. Factories, stores, hotels, restaurants, and other places employed White and Black employees, but deployed an “invisible wall” between job classifications that placed Black workers in inferior positions.31 Yet some of St. Louis was integrated: public libraries, public buildings, streetcars and busses, city-owned cafeterias, and some stores. Public housing and public schools, however, remained segregated. Public parks had dropped earlier restrictions, except at pools and athletic facilities. Unlike southern cities, and even some northern cities, St. Louis’s Jim Crow policing of urban space was not totalized, and allowed some actors (the housing authority, the parks department) to implement their own policies. The resulting landscape of civil rights posed contradictions useful to White power, even if it avoided more obvious extremes.32

The Police Department later proudly noted that officers refrained from using tear gas on the violent Black mob, an irony that has deepened with every tear gas canister used by the same department on peaceful civil rights demonstrations in recent years.

While Schermer’s attempts to make sense of the riot concluded that St. Louis was “psychologically unprepared” for the challenge of full civil rights, and had more in common with the South than the North in that regard, he did note some circumstances that cast the riot in a specific set of juridical conundrums. Noting that White residents realized that the city’s previous policy of barring Black residents from the pool was actually in violation of law, and not its fulfillment, the report also chastised the city for its execution of integration.33 According to Schermer, Baumes had been parks commissioner for eight years, and had presided over active discouragement of integrating recreational facilities. The sudden decision to integrate contradicted the parks department’s own practices, involved no planning, and lacked any public notice until the day before the pools opened.

To some extent, spatial conflicts reified economic conflicts in postwar St. Louis. After World War II, St. Louis saw continued in-migration of rural Americans both Black and White. White residents from the Ozarks, derogatively called “hoosiers,” arrived for factory jobs and put themselves in competition with existing blue-collar Whites.34 The Great Migration, meanwhile, became a more dire threat to the employment of White St. Louisans as well. The spoils of the employment office were dwindling, so much that by the late 1940s St. Louis stood as perhaps the third-poor-est city in the nation, with 15.3 percent of residents living in poverty.35

Yet industrial employment in aircraft manufacturing, chemicals, and other industries grew, portending recovery from the doldrums of the Depression.36 The stress on the emergent growth employment sectors stoked racial resentment among the White working and middle classes. St. Louis around the time of the Fairground Park pool riot saw increased hostility from White St. Louis toward new Black residents, with geography playing a secondary factory to wealth attainment. The animosity fit a national pattern of divided working-class race relations described by Manning Marable as “the logical culmination and popular expression of cultural/social patterns of race relations that increasingly pits the petty bourgeoisie, working-class, and permanently unemployed of different ethnic groups against each other over increasingly scarce resources.”37

Schermer fundamentally attributed the tensions at Fairground Pool to the city’s own careless decisions to suspend and enforce civil rights, which inflamed racist White attitudes and gave Black St. Louisans no reason to feel adequately protected by or included in government. The city government seemed to take little from his report, while perhaps the only public testimony of a changed conscience came from a 13-year-old White boy named Lynn who had taken part in the violence before participating in an integrated extracurricular program. Lynn admitted that he thought that Black people were “poor” and “mean,” and thus thought his participation was justified, but now understood that racism was wrong.38 City political leaders were recalcitrant by comparison. Darst eventually re-opened the pools as desegregated in 1950, but only after a federal court ruling, and again with little public engagement or endorsement of full equal rights.39 In 1954 the city government curiously boasted that it had integrated its recreational centers and pools starting in 1949, and that one-third of all users of facilities were now Black.40 This court-mandated progress was short-lived, and White attendance at Fairground Park pool declined to the point where the city closed the pool due to low attendance. (A smaller replacement opened on the site in 1964, and remains.)41 A few years later, when public housing desegregrated under court order in 1955, the same pattern occurred.

Figure 7: Director Charles Guggenheim inserted this dramatic re-enactment of the white violence against black swimmers, emphasizing the policing gaze and the participation of youth. Source: Still capture from film, Library of Congress.

Across Natural Bridge Road from the Fairground Park pool site is the mass of Beaumont High School (built 1925), also a key site in the integration of this part of north St. Louis. In 1954, the St. Louis Board of Education integrated the district to comply with the Brown v. Board of Education decision, after a previous campaign led in part by Teamsters Local 688 had failed. Beaumont High School opened to all students in September 1954, and in its first week of classes experienced a knife fight instigated by White students against Black classmates.42 The incident was rendered spectacular and overtly connected to the pool riot by director Charles Guggenheim, whose film A City Decides (1956) dramatized the events while suggesting hopefully that integration was a goal likely fulfilled and not deferred. Beaumont High School had no further incidents, and even became the school for three of the Little Rock Nine students after their families moved to St. Louis. Notably, both the integration of the Fairground Pool in 1950 and Beaumont High School in 1954 came through dictates of the federal government after failed local remedies for the city’s Jim Crow system.

St. Louis’s civil laws across the historic episodes that made Fairground Park’s setting the subject of Jim Crow practices embodied contradictions constituted through exceptions. Both the mayor’s allowance of the parks commissioner’s de facto integrate the Fairground Park pool and the city’s de jure enforcement of restrictions came without any legal instruments through ordinance—both were administrative decisions whose paper trails did not even include the annual reports of city agencies. Earlier, the suspension of picnic rights in the same area likewise came through the discretion of the city government, not through democratic deliberation or law. The earliest real estate development pattern relied upon the creation of a zoning law that eventually was rejected as unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court. The park landscape—like that of much of St. Louis throughout the twentieth century—was subjected to a series of state actions that were extra-legal unilateral actions of administrative power.

Beyond local lines, the Fairground Park incident mirrored national as well as local anxieties about the integration of recreational space in northern cities. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, fights against segregated pools in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh revealed the tendentious enforcement of Pennsylvania’s public accommodation law of 1939, which was effectively nullified by local police and White bullies.43 After St. Louis resumed integration, in 1952 Kansas City denied Black swimmers access to the Swope Park swimming pool, claiming its separate Black pool was adequate provision.44

Natural Bridge Road, the park’s southern boundary adjacent to the pool, was no longer a bulwark against Black migration, but more of a defensive line about to fall.

With the U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, a possible final rejection of local governments’ segregation of public spaces arrived. Federal lawsuits were still necessary to open access to southern swimming pools (and public housing in St. Louis) in the years after Brown v. Board of Education. By then, St. Louis’s Fairground Park pool was effectively segregating again, and the informal practices—what Mayor Joseph Darst had tried to pass off as innocent “community policies”—impeding Black St. Louisans’ access to public spaces did not end, even in locations White residents had abandoned.

Figure 8: The lake at Fairground Park. Source: Author photograph, 2017.

Today, the traumatic histories of Fairground Park lie concealed beneath an active landscape of public recreation frequented by Black St. Louisans. There are no monuments or markers to teach the story of the pool riot, although the outline of the old pool still reveals itself in aerial photographs. The 2014 conflicts over cruising, as well as the contemporary attention to adjacent concentrations of murders, serve as reminders that the attention and police powers of the state remain focused on Fairground Park. Can the state guarantee the safety and security of citizenship through uninhibited, free public use, or will they repeat past criminalization? Philosopher Giorgio Agamben posits that the presupposed “state of exception,” or the ability of a sovereign or state to selectively suspend civil rights and render subjects “bare,” is fundamentally a territorial rule that creates “bare spaces” simultaneous to “bare lives.”45

Fairground Park has been witness to the ways in which the state can make bare lives and bare spaces, not through hard laws but through soft powers, practices and exclusions buried in the hidden transcripts and code words of powerful White actors. Hopefully, the vitality of the roller rink demonstrates that Black St. Louisans have seized their rights to this landscape, boldly and fully, and cut loose the long reach of the lingering White territorial claim.