On July 4, 1874, the Eads Bridge (then called the St. Louis Bridge) opened to the sound of gunfire. At daybreak, the Simpson Battery fired thirteen guns for the original colonies; at 9 am, they fired one hundred, fifty from each side of the Mississippi River. The sides alternated shots, symbolizing a new era of cooperation between Missouri and Illinois. All day, citizens of the two states crossed from one to the other, supported by steel salvaged from Civil War gunships. A banner at the parade announced, “A link of steel unites the East and West.” A giant portrait showed two men, representing Missouri and Illinois, shaking hands. For all the commotion, the Eads Bridge also inaugurated moments of stillness. People stopped up there and looked, from a perspective entirely new. For the past century and a half, the bridge has been a favorite vantage point from which to view East St. Louis and St. Louis, Illinois and Missouri, East and West. Perhaps this is why the Eads Bridge has its own archive of interracial—and racializing—encounters. It has always been a site where people not only pass and cross, but also define and maintain borders.

Three moments stand out. The first, the bridge’s opening in 1874, asserted St. Louis’s place at the center of American empire after the Civil War. Then, thirty years after the opening celebration, the Eads Bridge acted as a technology of race and vision during the East St. Louis Pogrom of 1917. On July 2 and 3, 1917, White East St. Louisans planned and executed a pogrom against their Black neighbors. Thousands of refugees crossed the Eads Bridge and the newer Municipal Free Bridge to relative safety in St. Louis. The National Guard closed the Eads Bridge to traffic (late at night, after the damage had been done) to prevent more St. Louisans from crossing to join the rioting Whites. As African-American residents of East St. Louis fled the mobs, they passed White St. Louisans who gathered on the bridge to watch their city burn.

People stopped up there and looked, from a perspective entirely new. For the past century and a half, the bridge has been a favorite vantage point from which to view East St. Louis and St. Louis, Illinois and Missouri, East and West.

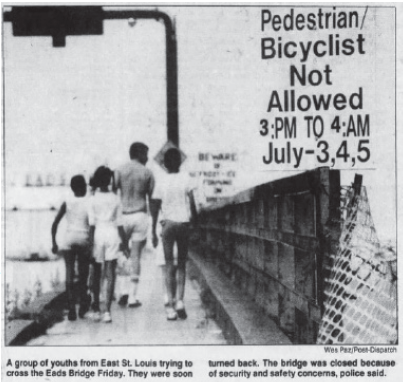

Finally, seventy years later to the day, the Eads Bridge emerged again as a site of racial violence and anxiety when police closed the bridge to pedestrian traffic. It was the weekend of St. Louis’s Fourth of July Veiled Prophet Fair, and authorities closed the bridge’s walkway as a security precaution. (The previous year, the press and police blamed teenagers from East St. Louis for crime at the fair.) The bridge became an experimental zone, where racist geographic imaginations (which in the 1980s equated East St. Louis with Blackness and crime) clashed with liberal fantasies of multiculturalism. On the Eads Bridge, we see the apparatus of hegemony at work, trying to fit all the bridge represents into the nation’s founding myths.

1874

What did Benjamin Gratz Brown see from the heights of the Eads Bridge on July 4, 1874, as he told the story of its construction to the crowds? The ex-governor and senator from Missouri saw Missouri, Illinois, the Mississippi River, and hundreds of thousands of spectators. He saw his younger self’s fantasy of a murderous manifest destiny fulfilled: the east and the west, meeting beneath his feet at St. Louis.

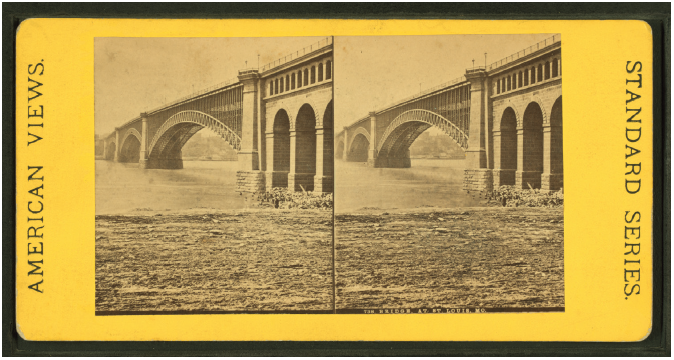

A stereograph shows the just-completed project. (New York Public Library)

The opening of the Eads Bridge in 1874 is a story of American imperialism, the shifting relationship of race and citizenship, and the consolidation of wealth and power through finance capital and civic works. From the words of the original financiers and engineers, it is clear that the Eads Bridge was always meant to assure the prosperity of the region (and, therefore, of the bridge’s investors) by connecting the spokes of American empire. (This narrative shines through two recent works on St. Louis history, Henry Berger’s St. Louis and Empire and Walter Johnson’s The Broken Heart of America.) What would the crowning of St. Louis as “the Queen of the West” mean in the era of Reconstruction and, as Du Bois called it, the “counter-revolution of property?”

Four years earlier, a St. Louis businessman had written to a potential German investor and prophesied that the bridge would “facilitate direct commerce with states west of the Mississippi, even across the Pacific Ocean.” Sure enough, as soon as the bridge opened, livestock was rushed into eastside meatpacking plants from the west. The Eads Bridge became a symbol of the region’s financial connections to not only the American southwest, but Central and South America as well. The St. Louis-based El Comercio del Valle, which ran from 1876 to 1890 and became the publication of the Mexican and Spanish American Commercial Exchange, featured an engraving of the bridge on its title page.

Despite (though also, in some ways, because of ) the commercial success the Eads Bridge facilitated, there had been many obstacles facing its construction. The cost was prohibitively high and the strength of the Mississippi at St. Louis made the engineering requirements of the bridge especially challenging to meet. What is more, interests from Chicago constantly worked the Illinois state legislature to prevent the bridge that might slow their city’s meteoric rise. The cooperation required to build the bridge says something about how a coalition of capitalists thought of civic projects in a time when the realm of the civil was hotly contested.

The fight to build the Eads Bridge cut across deep political rivalries, none more notable than that of Benjamin Gratz Brown and President Ulysses S. Grant. In 1872, Brown had run unsuccessfully for vice president on the Liberal Republican ticket opposing Grant and the entire project of Reconstruction. However, they shared an enthusiasm for the Eads Bridge. When Eads’s opponents tried to scrap the project just before its completion, President Grant stepped in to save it. In Brown’s speech at the opening celebration, he described introducing a bill authorizing the construction of a bridge at St. Louis in December of 1865, two weeks after the Committee on Reconstruction was established.

The bridge became an experimental zone, where racist geographic imaginations (which in the 1980s equated East St. Louis with Blackness and crime) clashed with liberal fantasies of multiculturalism.

The connection to Reconstruction is a reason to pause and return to the earlier question: what did Benjamin Gratz Brown see? More specifically, there is reason to wonder what Brown thought of the crowd that surrounded him that day on all sides, in two states. Brown spent much of his late-career campaigning against Reconstruction and restrictions on the rights of ex-Confederates in the name of reconciliation. In his earlier days as a Radical Republican, he advocated for the abolition of slavery because he thought it distracted from the nation’s ultimate goals of economic dominance and empire building. Just as the bridge connected geographies of empire, it also gathered a crowd that materialized Brown’s wish. Hundreds of thousands of people, not a decade after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, brought together by a new civil arena of empire and capital.

This view would have been an illusion. Before long, the bridge was owned by J.P. Morgan, and the railroads and ferry were controlled by Jay Gould. Three years after the opening of the Eads Bridge, an interracial uprising of laborers (many of whom must have marched in the Eads parade) brought East St Louis and St. Louis to a standstill in the Great Strike of 1877.

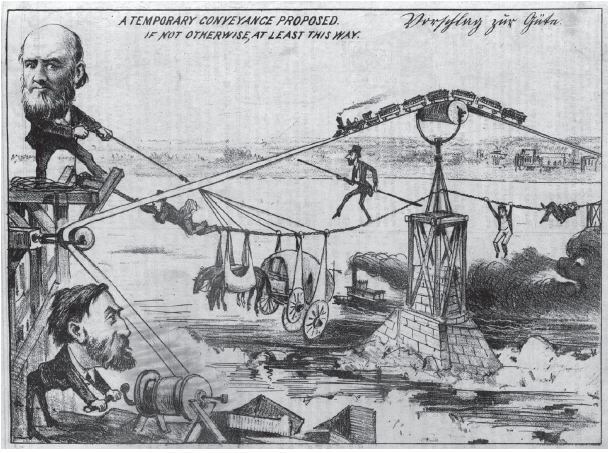

A political cartoon from 1872 poked fun at the project’s lengthening timeline. (Missouri Historical Society)

1917

During the 1917 pogrom of East St. Louis, the Eads Bridge was once again a key vantage point: both a technology used to redefine the region and the privileged site from which to watch it happen. The process of redefinition and the acts of seeing were not separate, but operated together within the logic of violence and spectacle.

In the decades following the bridge’s opening, the St. Louis region had been remade by the bridge, the railroads, and the economic concerns of those who owned them. The area around East St. Louis, in particular, experienced an explosion of industries, legible today as place names like National City, Granite City, and Alorton.

East St. Louis was a place of intense economic exploitation and political corruption, conditions that filtered through racial regimes to bring the city to the precipice of genocidal violence. In the first decades of the twentieth century, increasing numbers of African Americans settled in the area as part of the early days of the Great Migration. There, they met an intensely racialized structure of labor. Plants relied on Black migrants as a reserve labor force, available for unskilled work, particularly when White workers struck. Workplaces were segregated. Unions focused on organizing skilled labor, and many White workers argued for their promotion by asserting their difference from the new Black migrants. The year before the riots, 1916, saw accusations of a political conspiracy of Black “colonization” meant to threaten Woodrow Wilson’s reelection bid.

East St. Louis was a place of intense economic exploitation and political corruption, conditions that filtered through racial regimes to bring the city to the precipice of genocidal violence.

All this came to a head in the summer of 1917. According to historians Elliot Rudwick and Malcolm McLaughlin, each successive defeat of organized labor in East St. Louis ratcheted up the racism expressed by White workers. When an aluminum ore strike was crushed that summer, an unstated opinion of White labor became explicit strategy: for (White) labor to stand a chance, they thought, migration had to be stopped. The racism underlying this sentiment was shared by swaths of Whites in East St. Louis, in particular a kind of criminal class that was prominent in the riots.

On July 2, the climax of the summer’s violence, bridges across the Mississippi aided both mob violence and escapes from it. All day, White citizens crossed the river to participate in the riots. By seven in the evening, the National Guard stopped car traffic from St. Louis. Then, according to reports, “crowds crossed the Eads Bridge into East St. Louis by the thousands.” An hour or two later, the Eads Bridge and the newer Municipal Free Bridge were closed to all traffic from St. Louis, at which point, “curiosity seekers by the thousands were turned back at the St. Louis bridge approaches to the Illinois shore.”

This chromolithograph celebrating the National Democratic Convention features an image of the Eads Bridge. (Missouri Historical Society)

All day, Black East St. Louisans fled in the opposite direction, carrying whatever they could to St. Louis. Newspaper accounts explicitly contrast the movements of the two groups. While White mobs tried to push across the Eads Bridge, one reporter wrote that “hundreds of negro women, most of them carrying bundles that held their most precious belongings and leading small children, walked slowly across the bridge to shelter and safety with friends on the Missouri side.” Another described “Negro refugees by the hundreds, on the other hand, continued a steady stream over the municipal free bridge seeking a haven or refuge with friends in St. Louis.”

The mob’s goal was to make East St. Louis into a “sundown town,” a place so notorious for White supremacist violence that no Black people would dare move there. Moments of stillness on the Eads Bridge show the role that spectatorship played in this attempt at redefinition. Spectacular acts of violence required a wide audience to achieve their instructive ends. St. Louisans flocked to the Eads Bridge to watch East St. Louis burn. According to the Post-Dispatch, “From dusk Eads Bridge was thronged with St. Louisans crossing to see the fire and to witness the rioting… Many went no farther than the limit for returning without paying a second nickel, but hundreds of others pressed on toward the glow of the Broadway (Theatre) blaze.” Whether they stopped at the bridge or not, the East St. Louis pogrom was, for these St. Louisans, a paid attraction. The next day, officials in East St. Louis acknowledged the power of these images when they tried to prevent evidence of the pogrom from being documented. The Post-Dispatch reported, “Policemen this morning did their utmost to prevent the taking of photographs of the fire ruins or of the negroes’ bodies, still lying in the streets. ‘It’s the chief ’s order,’ they said. ‘East St. Louis doesn’t want that kind of advertising.’”

In 1917, the Eads Bridge and the Municipal Free Bridge catalyzed the East St. Louis pogrom. Both bridges allowed Black people to escape the pogrom and White people from St. Louis to join it. Focusing on these material sites reveals their role as technologies of definition, which, in the case of the Eads Bridge, is tied to its status as a vantage point. The clearest vision of the city’s potential future as a “sundown town” could be found on (or in view of ) the Eads Bridge: refugees were met by St. Louisans ogling, National Guard soldiers loitering, and rioters crossing. In the photograph on the front page of the July 3, 1917, Post-Dispatch, a “band of refugees [proceeds] westwards on Main street, toward the viaduct over Cahokia Creek, on the way to Eads Bridge,” which looms in the background.

1987

At 3 pm on July 3, 1987, police closed the Eads Bridge to pedestrian traffic. The next day in St. Louis was the Veiled Prophet Fair, founded in 1875 by the same elites who financed and profited from the Eads Bridge’s construction. The Veiled Prophet organization itself was a response to the labor unrest of 1875. The fair was meant to remind St. Louis of the munificence of its ruling class. In the 1980s, the VP Fair took place in downtown St. Louis, drawing millions of visitors each year. Guests included Dolly Par-ton, Barbara Bush, and Bob Hope. But if East St. Louisans wanted to enjoy the Independence Day festivities in 1987, they would have to find a ride.

The decision to close the bridge was the result of a moral panic that emerged from the previous year’s fair. In July of 1986, the Post-Dispatch reported on “the appearance of gangs of youth … [who] ran through crowds assaulting people and grabbing personal property, such as gold neck chains.” The mayor of East St. Louis, Carl E. Officer, told the Post-Dispatch “that since the fair, his officers had been recovering gold necklaces from East St. Louis gang members who lacked receipts for them.” In response to the reports of “chain snatching,” the Veiled Prophet embarked on a “regional plan” to police the next fair, involving the St. Louis Police Department, the Missouri legislature, the Missouri Highway Patrol, and the Illinois State Police. Part of the plan was to prevent people from crossing the Eads Bridge on foot.

After the dust had settled in 1986, there was only one specific case of chain-snatching that appeared in the local papers. An 18-year-old from East St. Louis with no prior convictions was sentenced to one year in prison for second-degree attempted robbery and third-degree assault. His defense attorney “[felt] the judge [was using] him as an example,” and the judge agreed. St. Louis Circuit Court Judge Thomas Mummert III told the Post-Dispatch, “I told him I hope the sentence sends a message to his friends…that we aren’t going to tolerate that kind of activity at our fair” (emphasis mine). Whose fair? The Veiled Prophet’s? St. Louis’s? The teenager from East St. Louis found himself on the wrong side of a line that was racial, economic, and geographic. Most literally, the dividing line was the Mississippi River.

That the panic surrounding chain-snatching was expressed through a fear of East St. Louis is not surprising. By the 1980s, St. Louis’s neighbor had become a metonym for Blackness and crime in the nation’s imaginary. (One popular reference point is National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983)—the Griswolds get their hubcaps stolen in East St. Louis.) All the factors that led to East St. Louis’s rise in the late nineteenth century made its fall even more dramatic. Deindustrialization hit the city hard. The factories that remained were far enough from the city to avoid taxes, but close enough to wreak environmental havoc. The population plummeted from over 80,000 in 1960 to 41,000 in 1990. White people fled. In 1990, the city was 98 percent African American. In their book on moral crisis and policing in 1970s Great Britain, Stuart Hall, et al., write that “in a class society, based on the needs of capital and the protection of private property, the poor and propertyless are always in some sense on ‘the wrong side of the law,’ whether they transgress it or not.” In 1987, East St. Louis was on the wrong side. The boundary line was zealously policed.

Yet, when it came time for the 1987 VP Fair and the police announced the Eads Bridge’s closure, there was near-unanimous condemnation from the public and the media. The East St. Louis chapter of the NAACP sued the St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners, the Illinois State Police, and the railroad association. Chief U.S. District Judge John F. Nangle ordered the bridge reopened to pedestrians. The police were caught entirely off guard, which is not surprising, considering the panic that put a teenager in prison only months earlier. Examining the content of these responses shows something other than a clear defeat of a racist policy, however. In letters to the editor, in staff editorials, and in the decision to open the bridge itself, we see an ideological affinity with the very plan protested.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

On the first day of the ban, a few hours before it took effect, the Post-Dispatch’s chief editor William Woo walked across the Eads Bridge. He reflected on his experience in the newspaper two days later, on the same day the bridge reopened. In Woo’s piece, the Eads Bridge is a vantage point. From its sidewalk, the vitality of St. Louis comes into view and becomes legible in contrast with East St. Louis’s desolation.

If St. Louis means vitality and East St. Louis desolation what happens on the Eads Bridge? Whether the answer is crime, racial transformations, or common courtesy, the question proved dangerous enough to close the Eads Bridge.

William Woo begins his narrative in East St. Louis, where he parks at an abandoned service station. The pumps are “smashed up”; the sidewalk is “cracked and buckled”; weeds grow through “broken beer bottles and fast-food packaging.” The only beauty on the east side exists despite its environment: “Some sunflowers and pink thistles manage to poke through.” As St. Louis comes into view, Woo subtly shifts his reader’s perspective from his own to a hypothetical East St. Louisan’s. “As you reach Missouri,” he writes, “the activity becomes even more impressive.” On the way back, “going home,” “desolation and emptiness” replace St. Louis’s vitality. Woo’s account constructs the same oppositional categories used by police to explain the bridge’s closing. In the reflection’s final image, a helicopter raises a giant flag above the east side, a “stunning sight” for those at the fairgrounds. For St. Louis to catch sight of (to define) its ideal self, represented by the flag, it must look to the east for comparison.

On the bridge, though, something else seems to happen. Small gestures, a word or two between strangers, call into question the totalizing implications of the symbols that dominate the pedestrian’s visions. “A black man, ahead of the curfew, passes. ‘How’s it going?’ he asks pleasantly. Farther on, two young whites have parked their bicycles to look at the river. ‘How’s it going?’ one says. On Eads Bridge, there is still courtesy among strangers.” This is a scene of multiculturalist tolerance of the other despite where they might be from or what they might look like. Yet, like the stories of chain snatching, it shows the hegemonic power of these places’ definitions. The scene illuminates in negative the dominant narratives Woo writes against. He includes this story of multicultural coexistence because the bridge’s closure assumes its impossibility, and thus makes it impossible. On the other hand, the scene also indexes the failure of the bridge’s symbolic meaning to account for its quotidian existence. If St. Louis means vitality and East St. Louis desolation what happens on the Eads Bridge? Whether the answer is crime, racial transformations, or common courtesy, the question proved dangerous enough to close the Eads Bridge.

A week later, the Post-Dispatch ran a series of “letters from the people” reflecting on the ’87 VP Fair. Six of the seven letters addressed the closing of the Eads Bridge. All of them criticized the closing. On one end of the spectrum, Christopher Tabron echoed Frederick Douglass: “Should black Americans celebrate the Fourth of July and the VP Fair? I find it ironic that they would.” On the other, A.J. Greenbank advocated “swift, certain and appropriate punishment for crime to remove offenders from law-abiding society” rather than collective punishment. All the other letters rebuked the closing on patriotic grounds that echo William Woo’s reflection. According to these letters, the closing of the Eads Bridge was antithetical to the nation’s foundational ideals. One writer went so far as to claim, “The framers of the Constitution would have almost certainly termed the Eads Bridge closure an ethically unwarranted and legally intolerable restriction of the commerce among the states.” These values are contrasted to those of other nations. Tim Pikarek asked, “St. Louis is not Johannesburg, now is it?”

The letters and William Woo’s reflection offer one surprising explanation for why the closure was condemned so soon after the panic surrounding crime at the fair: patriotism. Though the police’s plan followed popular conceptions of East St. Louis and a tough-on-crime ethos, the occasion of the closing—Independence Day—privileged national myths over local ones. The closing of the Eads Bridge offered the media, the public, and the judiciary an opportunity to reaffirm a hegemonic telling of the United States. In this narrative, which Jacquelyn Dowd Hall teaches us was a triumph of the New Right, the United States had long overcome its segregationist past.

The episode might have been embarrassing for the police, but it neither diminished their power nor generated a critique of their relationship to the state, media, or judiciary. None of the reflections in the press critiqued the forces of ruination at work in East St. Louis, nor did they suggest that St. Louis should have any responsibility for its mirror across the Mississippi. No one mentioned the 1917 pogrom. No one asked about the teenager who had been sent to prison.

• • •

These three stories are united by their setting, the Eads Bridge, and all seem shaped by it. In each moment, the cities on either side of the bridge asserted their relationship to each other and to the myths of the United States by calling on discourses of imperialism, patriotism, and White supremacy. In order to better see themselves—and close the difference between their mind’s eye and reality—people stepped up to the Eads Bridge and said what they thought they saw.

The closing of the Eads Bridge offered the media, the public, and the judiciary an opportunity to reaffirm a hegemonic telling of the United States. In this narrative, which Jacquelyn Dowd Hall teaches us was a triumph of the New Right, the United States had long overcome its segregationist past.

In 1917, White people in East St. Louis used the Eads Bridge and the Free Bridge in their attempt to turn East St. Louis into a sundown town, effectively driving their Black neighbors across the river. At the same time, the Eads Bridge offered White St. Louisans a place to pause and witness the pogrom. This act of witness turned the audience into performers themselves, observing the flames and repeating their message of White supremacy. Seventy years later, the police reactivated the Eads Bridge as a technology of definition, turning it into a physical manifestation of the line dividing Black from White, criminals from law-abiding citizens, poor from wealthy, “us” from “them”—a line that White East St. Louis tried to establish through extreme violence. The bridge’s reopening is thus best understood not as a challenge to racist policies but as an affirmation of national liberal myths of equality as a foundational value. At the Eads Bridge, between cities and among the crossing cars, the apparatuses of hegemony converge and show themselves.