Reflective, shiny in light, smooth and almost slick to the touch: this is a mirror’s materiality. Fingerprints—oil traces from a finger’s touch—also mark mirrors that have been touched and held. This materiality prompts questions. How does a mirror’s sensorial purpose—to reflect—frame how senses are trained and oriented? How does a mirror reflect and organize, and represent how concepts of beauty are illuminated? When a mirror fails, when it cracks, how does that failure situate aesthetics?

A casket’s materiality also prompts questions. A box often constructed with wood, a casket functions to hold a dead body. How do the materials, function, and aesthetics of a casket give meaning to a body that has lived and died?

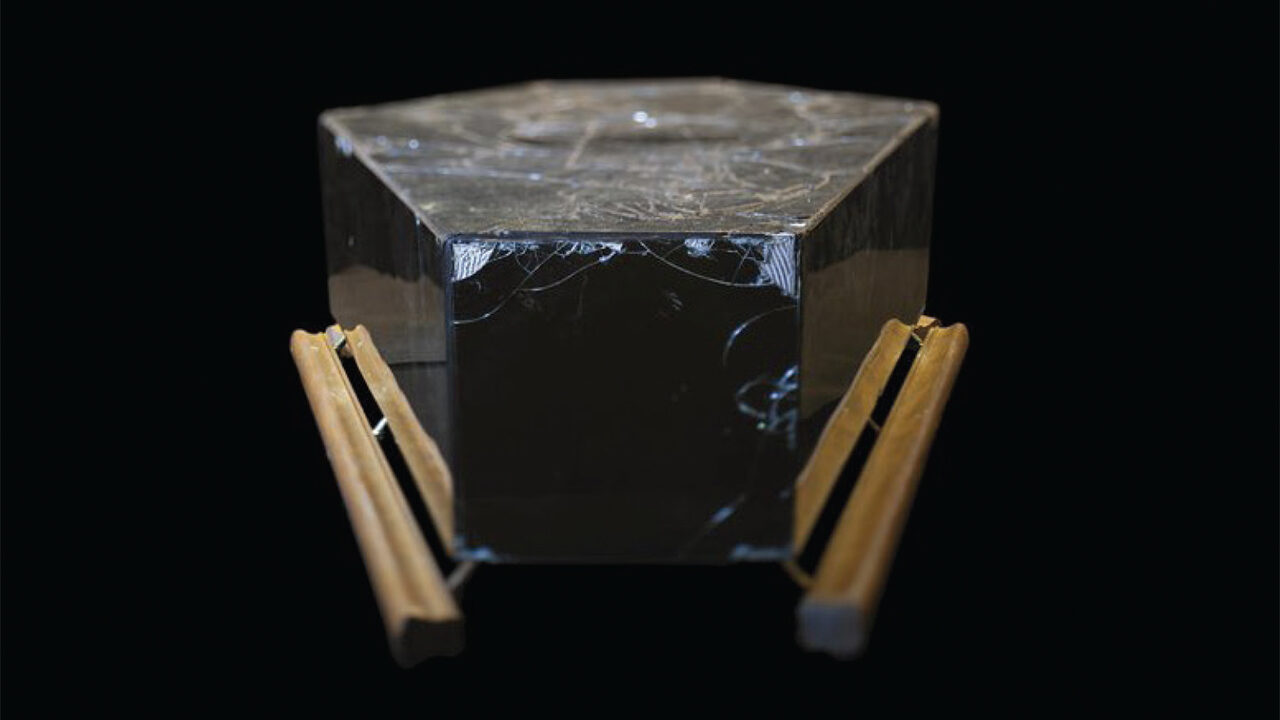

These questions animate Mirror Casket. A coffin covered with mirrors, the object was constructed in late summer 2014 by seven St. Louis-based artists, headed by De Andrea Nichols. The artists carried the casket during the Weekend of Resistance in Ferguson October, four days of protest organized in response to Michael Brown’s death. Their mile-length route extended from the site of Michael Brown’s death to the Ferguson Police Department. In months following, they and others walked the Mirror Casket in other protests across the United States. In 2015, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., collected this object; the institutional catalogue situates materiality: “Constructed from plywood, the top section and six side panels are covered with mirrored glass. The coffin handles are made from wood handrails which have been affixed to the base on four sides using metal handrail brackets. The composition of the top mirror panel has been intentionally cracked.”

Mirror Casket sits amongst a cohort of art created by Black artists in response to Michael Brown’s death. In 2014, Damon Davis generated All Hands On Deck, posters with images of multiracial sets of hands pasted on boarded-up businesses in Ferguson in November 2014 on the eve of the non-indictment of Darren Wilson; a website for All Hands On Deck included downloadable posters and directions for pasting so that anyone could print and paste the posters. Also in 2014, Damon Davis and Basil Kincaid created Hands Up, lawn sculptures traced from their arms and hands, and installed both on private lawns and public parks in St. Louis City and County. This essay documents these works. It asks: what can attention to aesthetic materials, sites, and discourses reveal about segregation in St. Louis in the 2010s?

Each work, I suggest, marks a material site of segregation in St. Louis, city and county. Defined, site means, “a place where a particular event or activity is occurring or has occurred.” Mirror Casket traveled from the site of Michael Brown’s death to the Ferguson Police Department; All Hands On Deck covered up boarded Ferguson businesses with the owners’ permission; Hands Up sculptures were installed in Black private lawns, marking private Black geographies, as well as in a public park in mostly White Kirkwood, Missouri, a St. Louis County municipality.

This work also reveals the sensorial dimensions of the region’s racial segregation. Among the reflections in Mirror Casket were faces of mostly White police officers who looked at the object as they faced protesters. Unlike the region’s racial segregation, the racially diverse images in All Hands On Deck were pasted next to one another. Hands Up framed the African-American body as necessarily compliant with law enforcement. The sculptures also marked juridical geographies of racial segregation: they were installed in a public park in mostly White Kirkwood, where St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch lived and oversaw the proceedings that led to the non-indictment of Darren Wilson who shot Michael Brown in mostly Black Ferguson.

Mirror Casket cared for, even if symbolically, a dead Black body. This care contrasted to how the police treated Michael Brown’s body, which lay in the street for four hours after his death.

In revealing the sensorial dimensions of segregation, this art also did other work. Mirror Casket cared for, even if symbolically, a dead Black body. This care contrasted to how the police treated Michael Brown’s body, which lay in the street for four hours after his death. All Hands On Deck aligned hands of different races and adorned businesses with the owner’s permission, marking businesses sympathetic to Michael Brown’s life and to protesters demanding justice at a time when media reports positioned the protests as destructive. Hands Up included some hands in the shape of fists, positioning African-American interiority as quietly resistant to how Blacks are often compelled as necessarily complicit by law enforcement. Each work, then, produced ways of sensing logics of segregation, and incited a different way of sensing that imagined and rehearsed more racially equitable and just geographies. Defined, sight means “a thing that one sees or that can be seen.” This art produced by Black artists in response to Michael Brown’s death, then, sited and sighted segregation.

Mirror Casket

In Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old Black youth, was shot and killed by Darren Wilson, a 28-year-old White Ferguson police officer. After his death, Michael Brown’s body lay in the street for four hours—police did not let his mother attend to him. Following Brown’s death, Nichols begun having nightmares. She told me:

Whenever I would sleep on those nights following [Michael Brown’s death] I would always have these nightmares. Some of the nightmares were about my brothers … any of them could be another Mike Brown. My youngest brother … [i]t pains my heart that there are people in this world that want to make him a Mike Brown, you know?

Each night while sleeping, her nightmares continued, and continued to transform.

Those nightmares also turn into this manifestation … of men just walking, carrying in this casket that was made completely out of mirrors, and it was always pitch-black in my dreams.

Nichols could not shake the image of the coffin made out of mirrors. So one day, she decided to sketch it. Nichols herself grew up in rural Mississippi; she moved to St. Louis in 2006 to pursue a B.A. in communication design from Washington University in St. Louis, and later a Master’s of Social Work. After graduating, she worked at the Contemporary Art Museum as the community engagement manager. She also founded Civic Creatives, a business where she collaborated with photographer Attilio D’Agostino to produce Faces of the Movement, an online photography catalogue that according to their website “share[d] the stories and faces of individuals who invest their time, livelihoods, and lives in the national Movement spurned across the United States since August 9, 2014.” Storytelling, civic engagement, and social impact, then, roots Nichols’s work and art.

After seeing the image, Nichols emailed artists in St. Louis and asked for their help in realizing her sketch. Among them: Marcus Curtis, a carpenter and “the only White guy on our team”; Sophie Lipman, from the Pulitzer Art Museum in St. Louis; Damon Davis, assistant builder; Elizabeth Vega, founder of Artivism in St. Louis; Derek Laney, organizer and artist; and Mallory Nezam, a performance artist. Many had protested in Ferguson in August on the nights following Michael Brown’s murder. The media forecasted the situation as “wild,” but Nichols found a collaborative environment with “drummers drumming and people singing and chanting.”

By now it was October 2014, and Nichols and her team realized the Mirror Casket. The object, covered with mirrors, had dimensions similar to many caskets, some seven feet by three feet by two feet. But mirrors and movement made the casket more than an object. “Working with some performing artists,” Nichols told me, “we organized this whole notion of taking it and moving it and performing with it.” They walked with the mirror casket during the Weekend of Resistance in Ferguson October, four days of protest, “from the site of Michael Brown’s death to the police department.” Facing the police, Derek Laney asked officers to look at the object, to look at themselves. Thus the casket became, as the artist statement also described, a “performance, and call to action for justice in the aftermath of the murder of Michael Brown.”

Defined, sight means “a thing that one sees or that can be seen.” This art produced by Black artists in response to Michael Brown’s death, then, sited and sighted segregation.

Mirror Casket, then, in its walk from the site of Brown’s death to the police department, sited segregation in Ferguson. It connected Brown’s death at the hands of law enforcement to carceral geographies in Ferguson. Damon Davis, an artist on the project, told me:

These cops don’t even go to fucking trial. They don’t even go to trial. Not that they don’t get convicted, they don’t even go to fucking trial.

Mirror Casket also held this tumult; it anticipated U.S. Department of Justice findings eighteen months after Michael Brown’s death that, as a Washington Post article detailed, “[T]he city’s police and court system continue to violate Black residents’ civil rights” (Berman, et. al.). The article continued describing how the report:

allege[d] that Ferguson’s police department and municipal courts engage in an unconstitutional ‘patterns and practices’ of using force without legal justification and ‘engaging in racially discriminatory law enforcement conduct.’

Federal officials say the civil rights violations stem from the city’s failure to properly train and supervise its law enforcement officers, echoing the findings of the 2014 Justice Department investigation into Ferguson’s police force. (Berman, et. al.)

In its walk, in its demand that police officers look at the object, Mirror Casket sited this.

In Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practices, art historian Krista Thompson analyzes Black aesthetic practices that trade in reflection and light. She writes:

What I describe as a visual economy of light is in part a product of everyday aspirational practices of Black urban communities, who make do and more with what they have, creating prestige through the resources at hand. But these very processes can have a critical valence because they have the potential to disrupt notions of value by privileging not things but their visual effects … a new, ever-changing and unpredictable community of viewers is created who reconstitute and reenvision value.

Mirror Casket, as read through Thompson, reconstituted a value of Black life and Black death. The casket’s materiality—covered with reflective mirrors, hollow, and big enough to contain a body—not only signified the dead body, it also oriented the senses to reflect upon treating the dead body with respect and care. The casket was heavy—those holding it had to do so with strength; fingerprints left on the mirror traced not associated tropes of Black criminality, but rather marks by those who carried the casket and symbolically cared for Black people, Black life, and Black death. By contrast, once killed, Michael Brown’s dead, uncovered body lay for four hours before being moved.

Reflect means to “throw back without absorbing,” to show an image of, to embody or represent. Faces of those holding the casket, faces of protesters, faces of police officers, faces of community members, faces of those present at the event were all reflected in the mirrored coffin as Nichols’s team walked it through the crowd. The mirrors, like mirrors do when they are touched and moved, eventually cracked and refracted, or changed direction in reflection. In the months following Ferguson October, following the non-indictment of officer Darren Wilson, the Mirror Casket was carried in rallies nationwide, throwing back and changing the direction of the reflections of protestors, police, and observers.

But there was a quietness with Mirror Casket, too. Mallory Nezam, another artist, told me:

We did have candles. We had a procession. We walked a mile. We let people express however. … This was just more of a collective march. It was nighttime so it was pitch-black. We were going down a lot of residential streets. … I’ve never done a march that was in such a residential area. In a way it kind of was quieter than it typically is.

With quietness: reflection. Krista Thompson also writes “shine may be understood as part of a Black popular cultural and scholarly approach that is attentive to diasporic peoples’ intrinsic place within, estrangement from, or relationship to modern capitalism and Western societies’ definition of citizenship.” Nichols and her team created an object and a performance that forced the temporary community of spectators to site and sight segregation, that is, to reflect upon how the treatment of Black people in the United States often reveals an estrangement from ideals of modernity, and how Black bodies alive and dead should be treated differently—with more respect and care—than they often are. Mirror Casket incited a thinking and reflection about Michael Brown’s life and death that was not given to him as his dead body lay on the street. Holding the casket, the artists rehearsed a practice of how Black people should be held and treated with care, dead and alive.

All Hands On Deck and Hands Up

On Thursday, November 20, 2014—a month after walking with Mirror Casket through Ferguson October—a cohort of St. Louis-based artists pasted posters onto plywood boarding businesses in Ferguson. The image of each poster: a set of hands from children and adults of various races. All Hands On Deck was an art project begun by Damon Davis, a St. Louis-based artist (who worked on Mirror Casket), after he encountered Michael Skolnik, Global Grind editor-in-chief at a rally in Ferguson. The two brain-stormed a project to engage feelings of racial inequality and unrest shaping the movement emerging from Michael Brown’s murder. Davis wrote:

The hands you see are images I have captured of people who have shaped and upheld this movement. The peoples movement. It is our right—to be seen, to be heard … to be validated. It is our collective responsibility. The All Hands On Deck project is an ode to that diverse collective dedicated to protecting our human rights, no matter race, age or gender. All Hands On Deck is our charge—a call of action to stand with those who stand for us all.

Covering part of the plywood, the posters appeared as an iterative array, each positioned next to one another, making horizontal rows on businesses such as Ferguson Market & Liquor, Prime Time Beauty & Barber, and Crystal Nails. Zak Cheney Rice, writing for Mic, described All Hands On Deck as “the most powerful street art in America.” Days later, on Monday, November 24, 2014, a grand jury returned the verdict that Darren Wilson would not be indicted.

Nichols and her team created an object and a performance that forced the temporary community of spectators to site and sight segregation, that is, to reflect upon how the treatment of Black people in the United States often reveals an estrangement from ideals of modernity, and how Black bodies alive and dead should be treated differently—with more respect and care—than they often are.

Born in East St. Louis, Illinois, and based in the city of St. Louis, Missouri, Damon Davis has made art for most of his life, and professionally since the twenty-first century. His artist statement includes:

My practice is part therapy, part social commentary. I work across a spectrum of creative mediums to tell stories. … I have found in my recent years, I have been making art to empower the disenfranchised and powerless, and to combat the system oppression that plagues our world today. M[y] work is rooted in the Black American experience, because that is my experience. … I am having a conversation with myself when I work and when that conversation is made public, my hope is that people can see themselves in my struggle and it helps them grow, along with myself.

His work includes the Negrophilia series,“a personal meditative and therapeutic tool…to deal with the constant stress of what was happening in my hometown of St. Louis after the murder of Michael Brown and subsequent uprising.” It also includes music, and film, such as Whose Streets?, a 2017 documentary film about the 2014 uprising in Ferguson, co-directed with Sabaah Folayan.

To make All Hands On Deck, Davis took pictures of protestors during the cold of November. He narrated to me:

I went around, I took the pictures [of ] all those people that were active people in the movement; Black…White…straight… gay… young…old. Everything, but that’s the community that was standing up for what was going on.

The pictures of the hands, then, were not just a referent-neutral racially diverse set; they signified the diverse people involved in the Ferguson movement. Davis also produced this art as “a gesture to let the community know that we stand with you.” He continued:

The morale was down, it was cold. We had been out there for months. People was getting tired, man. And that still was the point. That’s why [the police] kept pushing back, so that people would quit protesting. They thought they was going to go in a house when it got cold. It’s all warfare. It was all fucking warfare. That was supposed to be a boost, supposed to be a morale boost, and it worked as far as I know.

The project, then, also sought to boost morale for protestors who had demonstrated for months.

All Hands On Deck sited segregation in Ferguson. In 1970, Ferguson, the North St. Louis County municipality, had a population of 28,759 that was 99 percent White and 1 percent Black. In 2010, Ferguson had a population of 21,203 that was 29.3 percent White and 67.4 percent Black. Although majority Black by 2010, Ferguson city officials were, at the time of Brown’s death, mostly White.

Revenue-raising schemes in Ferguson demonstrated this racial difference. In a March 4, 2015, New York Times article, “A City Where Policing, Discrimination and Raising Revenue Went Hand in Hand,” Campbell Robertson reports how White Ferguson officials extracted revenue by fining Black residents for benign quotidian acts framed as infractions. The article begins:

A 32-year-old black man was sitting in his car, cooling off after playing basketball in a public park in the city of Ferguson, Mo. Then a police officer pulled up.

The officer approached him and demanded his identification. He then accused the man of being a pedophile, since there were children in the park, and ordered him out of his car. When the man objected, the officer arrested him and charged him with eight violations of Ferguson’s municipal code, including a charge for not wearing a seatbelt, even though he was in a parked car.

This encounter in summer 2012 in some ways appeared to be exactly how the criminal justice system in Ferguson had been designed to work, according to an investigation of the Ferguson Police Department released on Wednesday by the United States Justice Department. As described in the report, Ferguson, which is a majority Black city but where nearly all city officials are White, acts less like a municipality and more like a self-perpetuating business enterprise, extracting money from poor Blacks that it uses as revenue to sustain the city’s budget.

The article continues, describing how White officials in Ferguson fined Black residents for benign actions such “as ‘peace disturbance,’ ‘failure to comply’ and ‘manner of walking.’ For all three violations, more than nine out of 10 of those cited were Black.” Black residents were fined for benign quotidian actions including walking and sitting while Black.

In her 2011 article in Social and Cultural Geography, “On plantations, prisons, and a Black sense of place,” Katherine McKittrick suggests that the Black condition in the United States is one of urbicide, “the deliberate death of the city and willful place annihilation.” Urbicide, she suggests, then, “can stand in as a viable explanation for the ongoing destruction of a Black sense of place in the Americas.” Urbicide frames these fines in Ferguson, Missouri, that raise revenue from Black quotidian actions. McKittrick details “the material consequences of urbicide in the Americas,” which include “burned up, bombed out, flooded, crumbling buildings, and infrastructural decomposition.” (952) Although depersonalized, urbicide, as McKittrick writes, is also a “very human [and] racialized, activity,” that includes the persistent fines against Black people for being while Black. Thus, sensorial and embodied and geographically-situated dimensions to urbicide, to the deliberate destruction of the city, exist. All Hands On Deck sited this urbicide, this material segregation; it covered businesses prior to protests, protests that demonstrated against how racist policy produced in McKittrick’s words “[t]he deliberate destruction of the city.”

Many naturalize Ferguson as racially segregated, but the municipality is actually a space always in process, a space produced by policies and actions. In How Racism Takes Place, sociologist George Lipsitz writes, “These spaces make racial segregation seem desirable, natural, necessary, and inevitable. Even more important, these sites serve to produce and sustain racial meanings; they enact a public pedagogy about who belongs where and about what makes certain spaces desirable.” (15) But art can intervene in how sites “sustain” naturalized “racial meanings.” With multi-racial images of hands, with consent from business owners, All Hands On Deck denaturalized racial politics of space in Ferguson and produced new material practices that supported the often-demonized protesters.

For example, the website documenting All Hands On Deck includes instructions for those wishing to replicate the project’s art: “Download and print the hands (or make your own) and post them in your city,” text on top of the “Get Involved” page reads. There are four steps: “Print the posters,” “Mix the paste,” “Post,” and “Action.” Under “Mix the paste” is a recipe for wheatpaste that includes mixing one and a half parts water and one part flour “in a large pot, bring to boil. Don’t stop stirring.” Directions for “Post” are both practical and political: “Roll or brush on thick layer of paste…[a]pply the poster, smooth out evenly to get rid of bubbles,” and “Pick targets wisely: high visibility is good, think about who owns/maintains the space you’re pasting. Asking folks permission gets them involved in the project…talk to folks. Let them know what this is about.”

Urbicide frames these fines in Ferguson, Missouri, that raise revenue from Black quotidian actions. McKittrick details “the material consequences of urbicide in the Americas,” which include “burned up, bombed out, flooded, crumbling buildings, and infrastructural decomposition.”

Paste is something most everyone can make; pasting the posters on plywood is something most everyone can do. These instructions position Davis’s materials as accessible; readers can download a poster, and the materials for the paste include items found in many homes. The accessibility of the materials ties to Davis’s goal as an artist. He said: “This is a problem that is going to take everyone to fix. It is all hands on deck” (“Ferguson ‘Hands’ Together”). Partially covered with posters, the still visible plywood suggested the businesses—boarded up due to protests—supported the aesthetic action linking hands and community members in Ferguson. There is a loud public resistance to the posters of hands pasted onto plywood. The materiality—the accessibility of paper, the stickiness of paste, and the iterative racially diverse images of hands—also suggests a collaborative, integrated aesthetic that contrasts to the racial segregation produced by racist policies destructive of quotidian Blackness.

The posters were also pasted upon boarded-up businesses, with permission of the owners, suggesting geographies sympathetic with protestors often portrayed as destructive, and rehearsing a different relationship between Black residents in Ferguson and revenue: business geographies supportive of, rather than extracting revenue from, Blackness. McKittrick describes a Black sense of place as “materially and imaginatively situating historical and contemporary struggles against practices of domination and the difficult entanglements of racial encounter.” (949) All Hands On Deck sighted logics beyond segregation by revealing businesses supportive of racially-equitable geographies, and supportive of a Black sense of place in Ferguson.

Earlier in 2014, blades of grass stretched to ordinary heights of two and three and four inches tall. Amidst these blades stood not-so-ordinary objects: pairs of arms. Each pair was a “lawn sculpture” representing human arms and hands. Each rose some two feet tall; each appeared as a flattened two-dimensional representation in Black; each began in the grass seemingly where the elbow would start. Most sculptures ended two to three feet off the ground with fingertips of each hand outstretched. Others varied, with one hand with outstretched fingers and the other hand with fingers closed in a fist. This was Hands Up, sculptures by Damon Davis and Basil Kincaid.

The installation in Kirkwood suggested a sensorially geographic dimension to segregation: decisions that affect Black life are often made far from Black people.

Damon Davis had worked on Mirror Casket and All Hands On Deck; Kincaid is a fellow St. Louis-based artist whose “quest,” according to his artist statement, “is to understand the wild tapestry of my own personal identity and cultural identity within the African Diaspora, contextualized by the framework of my American experience.” The title Hands Up evokes what many witnesses to Michael Brown’s death recall were his last words, “Hands Up Don’t Shoot.” The sculptures were installed in 2014 on lawns of homes in St. Louis and in Walker Park in Kirkwood, near the home of St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch, who oversaw the proceedings that led to the non-indictment of Darren Wilson. There was a stillness, altered naturalness, and quiet resistance (citing scholar Kevin Quashie) to “Hands Up” sculptures. These were cut from wood after Damon Davis and Basil Kincaid traced their arms and hands.

The sculptures marked public geographies in dialogue with the prosecution of Darren Wilson, and juridical geographies of segregation. They were installed in private lawns, marking private Black geographies, as well as in a public park in Kirkwood, which is 96 percent White and 2 percent Black. Ferguson, in 2010, was about 67 percent Black and 29 percent White. The installation in Kirkwood suggested a sensorially geographic dimension to segregation: decisions that affect Black life are often made far from Black people.

Davis and Kincaid installed the sculptures in a variety of locations. The materiality of the Hands Up and the ease of moving the sculptures suggest the prevalence and ease of police violence against Black subjects. Hands Up also sighted segregation, that is, by producing ways of sensing logics of segregation, and inciting a different way of sensing that imagined and rehearsed more racially equitable and just geographies. The existence of fists among the open hands suggests the potential for pervasive resistance, positioning African-American interiority as quietly resistant to how Blacks are often compelled to be necessarily complicit by law enforcement. Hands Up sculptures were also staged on private lawns, and the arms were drawn from the artists’ own bodies, suggesting a quiet interiority (Quashie).

Re-sighting race in art regimes of twenty-first-century segregation

In this essay, I have documented art produced by Black artists that suggest a sensorial dimension to modern segregation and a rehearsal of more racially just practices. The emphasis on art by Black people is significant: ideas of Blackness have long been produced by non-Black people. In the nineteenth century, White New York City actor T.D. Rice “invented” Blackface performance, ostensibly based on a dance and song performed by a Black slave. More recently in St. Louis, White artists have produced ideas of Blackness.

In 2016, the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM) exhibited Direct Drive with works by American artist Kelley Walker, a White male artist. “AquaFresh plus Crest with Whitening (Trina)” included an oversized print of a King magazine cover with the image of the rapper Trina; Walker manipulated that image by smearing it with toothpaste and by mounting the image both on the wall and on the floor. Toothpaste evoked semen; the position on the floor allowed museum visitors to step upon an image of Trina’s, a Black woman’s, body. In “Black Star Press,” Walker blotted images from the civil rights movement with chocolate. “From a distance, it’s hard to discern if the smears are those of chocolate or excrement,” critical theorist Rhaisa Williams wrote of this work in her 2018 essay “Choregraphies of the Ongoing: Episodes of Black Life, Events of Black Lives.”

At an artist talk on September 17, 2016, at CAM, Kelley Walker was unable to articulate why he used those substances to smear and obliterate images of Black bodies; more broadly, he was unable to articulate his ideas on race, materiality, and art. In the week following, several things happened: artists including Davis called for a boycott of Direct Drive (Davis authored a public Facebook post: “If you are an artist and you are making work that is specifically racially and sexually charged, if you use Black people for props in your work, then at least be ready to explain yourself ”); a previously-scheduled talk at CAM, “Critical Conversations: Art and the Black Body,” was retooled to discuss the controversy with a panel featuring St. Louis Black artists and a standing-room crowd of over 300 hundred attendees; leadership at CAM decided to place walls around “AquaFresh” and “Black Star Press”; and Paula Cooper Gallery, the New York-based gallery representing Kelley Walker, released a statement defending Walker’s art. The statement did not focus on Walker’s materials (toothpaste, chocolate), but rather on how images of the Black body always already circulate, and how Walker’s job as an artist was to raise questions and not answer them.

Williams also writes of the CAM incident attentive to materiality:

So, for Kelley Walker to have the audacity to be offended that he, as a White artist, would have to explain his work that literally smears oral products that resemble bodily excretions on made images of Black bodies? No, that is not going to fly in a place like St. Louis. St. Louis has been imprinted by the scene and after-math—affective and visceral—of the murder of Michael Brown, Jr. (nationally known as “Mike Brown,” locally known as “Mike Mike”). Drive along Union Avenue, one of the city’s main streets, and you’ll see “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!” spray-painted on the sides of commercial buildings or on abandoned residential homes.

Through Williams, we might ask: what does it mean for White artists to not be accountable to the meanings they make of Black people, and the materials on which those meanings rest? “These people always think they could tell us more than we could tell ourselves,” Damon Davis told me about the Walker incident, “about lived experience.” He continued: “If you want to do a real analysis about race and culture in this country, why don’t you get a Black artist from St. Louis?”

In August 2016, the Center of Creative Arts (COCA), a St. Louis based arts center, exhibited Outside In: Paint for Peace. The exhibit featured panels painted with art, panels that once covered businesses boarded up in the wake of protests after the murder of Michael Brown. Curated by Jacquelyn Lewis-Harris, associate professor at the University of Missouri, St. Louis, Outside In was institutionally collaborative, simultaneously on view at other area centers including Gallery 210 at the University of Missouri, St. Louis; Missouri History Museum; Vaughn Cultural Center; Sheldon Art Galleries; and Ferguson Youth Initiative. There was a jubilant colorfulness to the boards-turned-murals collected in Outside In. But that colorfulness mostly often hid a direct confrontation with issues raised by Michael Brown’s death: systematic, racially motivated, police brutality, discrimination, and exploitation. Davis said of Outside In:

[T]hese liberal … people painting “Let’s all get along.” That … disgusts me, because it ain’t about us all getting … That’s like putting a kid and a molester in the room and telling them to work problems out. One … is the aggressor and the other one is not. It’s not about working things out. It’s always this, “Oh, kumbaya,” because you would implicate yourself. You hear me? You would implicate yourself because…you get the benefit off of it, right?… And they’re painting, literally painting band-aids on St. Louis…like that.

At the September 16, 2016 curator’s talk at COCA, which I attended, artists (mostly White, and a few Black) who produced the murals detailed their process; one, a White woman, suggested she painted to make Ferguson beautiful again; another, a White man highly involved with dis-tributing paint, said, “[M]y one rule for everyone involved: do not talk about politics.” Both suggested that the materials—bright paint—used to make the murals coincided with silencing of racial politics tied to Michael Brown’s death. Both Direct Drive and Outside In: Paint for Peace centralized materiality to silence discourses of race and racial segregation, and produced surplus-value of Blackness as something to be smeared, stepped on, and not talked about. Both were examples of ideas of Blackness mostly produced by non-Black people.

Mirror Casket re-framed order to hold and care for a dead Black body when Ferguson police officers would not; All Hands On Deck positioned businesses sympathetic to protestors when many Black residents in Ferguson were abused by civic revenue-raising schemes; Hands Up re-situated how White geographies influenced juridical decisions that affected Black life and death.

Hortense Spillers has detailed the Black woman’s body as “signify-ing property plus;” (65) Michael Rogin has detailed the filmic and visual “surplus symbolic value of Blacks, the power to make African Americans stand for something beside themselves.” (417) Both scholars suggest the Blackness exceeds itself; racial markers of difference that mark the Black body produce surplus value that distorts the humanity of Black subjects. By contrast, the art documented in this essay, Mirror Casket, All Hands On Deck, and Hands Up, revealed aesthetic manifestations of Blackness created by Black people, indicators into embodied racialized experiences in “post-Ferguson” St. Louis that disrupt existing discursive ideas about race, and in doing so both site and sight segregation, giving voice to the burdens and imaginations of Black people.

Conclusion: towards an aesthetics of listening

I want to close this essay connecting the art documented here with what Fred Moten writes about Emmett Till and the photograph of Till’s open-casket funeral. In 1955, Till, then a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago, was brutally murdered by a gang of White men in Mississippi while visiting relatives. Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to give her son an open-casket funeral so that onlookers could witness the brutality committed to his body. After Michael Brown’s death, many—including then U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder—compared Brown’s death to Till’s. In “From Emmett Till to Michael Brown, a story as old as America itself,” former Ohio Governor Ted Strickland and attorney Judith Browne Dianis wrote: “It’s all too familiar, from the blaming of the victim to the community outcry, and is yet another example of how this nation has long devalued the lives of its black citizens. Instead of trust and healing, the streets of Ferguson were full of tear gas and militarized police. In the place of justice, there is only anger, reminiscent of scenes we have seen before.”

In his 2003 essay, “Black Mo’nin’,” Fred Moten offers three ideas useful to this essay. First, he rightfully maintains that Till’s death was not natural. He writes:

Of course, Emmett Till’s death (which word wrongs him and her) was not natural, and the photograph shows this. It shows this and the death’s difficulty, the suffering of the mother, the threat of a high mortality rate, and the seemingly absolute closure of his future. (71-72)

Moten’s theorizations highlight how the murder of young Black people is not natural, as does the sensorial engagement with the materials of art in this essay: holding a casket with care, adorning businesses in Ferguson sympathetic to Brown’s life, siting how White geographies in segregated St. Louis County influence juridical decisions in a mostly Black city.

Second, Moten suggests that looking at the image of Till’s body incites an interlinked aesthetics and politics. He writes:

This is to say not only look at it but look at it in the context of an aesthetics, look at it as if it were to be looked at, as if it were to be thought, therefore, in terms of a kind of beauty, a kind of detachment, independence, autonomy, that holds open the question of what looking might mean in general, what the aesthetics of the photograph might mean for politics, and what those aesthetics might have meant for Mamie Till Bradley in the context of her demand that her son’s face be seen, be shown, that his death and her mourning be performed. (63)

Aesthetics, as philosopher Katharine Wolfe frames, are the “proper and harmonious organization of senses”; politics, as theorist Caroline Levine frames, are “a matter of imposing order on the world.” (x) Through these theorists, including Moten, we can think about how Black aesthetics re-orient the senses to re-situate how order is imposed on Black people. Mirror Casket re-framed order to hold and care for a dead Black body when Ferguson police officers would not; All Hands On Deck positioned businesses sympathetic to protestors when many Black residents in Ferguson were abused by civic revenue-raising schemes; Hands Up re-situated how White geographies influenced juridical decisions that affected Black life and death.

Third, Moten identifies the importance of what this entanglement of aesthetics and politics produce: listening. “We have to keep looking at this so we can listen to it,” he writes, asking that we continually and sensorially attend to aesthetic works to listen to them. (72)

In this essay, each work’s materiality disrupted the naturalization of segregated anti-Black space in St. Louis and produced embodied strategies of reclamation. Mirror Casket reclaimed both the aesthetics and act of mourning; All Hands On Deck reclaimed the space of boarded-up buildings as a means to support protesters; Hands Up, through its materials and locations, suggested strategies for reclaiming space by reinserting narratives into those spaces. If we keep looking at Mirror Casket and the reflections in it; if we keep looking at All Hands on Deck and the hands on the posters and businesses they adorn; if we keep looking at Hands Up and its geographies—if we keep looking at this art work and how it orients our senses—we might be able to listen to sites of segregation, to Black experience, and to rehearsals of more just geographies, and sights beyond those sites.