Special thanks to editorial board member Greil Marcus and executive committee member Chakravarthi Narasimhan.

By

Chris Estey

Until I could find an apartment, I rode the No. 6 bus up and down Highway 99 most of the night, from downtown to Aurora Village, listening to muffled, skewed robotic drum beats of fellow travelers from behind the earphones of turned-up Walkmans, looking out into the dark. No, scratch that, looking at myself in the reflection of myself on bus windows in the dark.

By

Sarah Dougher

The complicated relationship between girls and music, and the mobility that it both affords and denies them, is only legible through conversations with girls. As it turns out, the music of Katy Perry makes that relationship most legible.

By

Gerald Early

The Common Reader on popular music

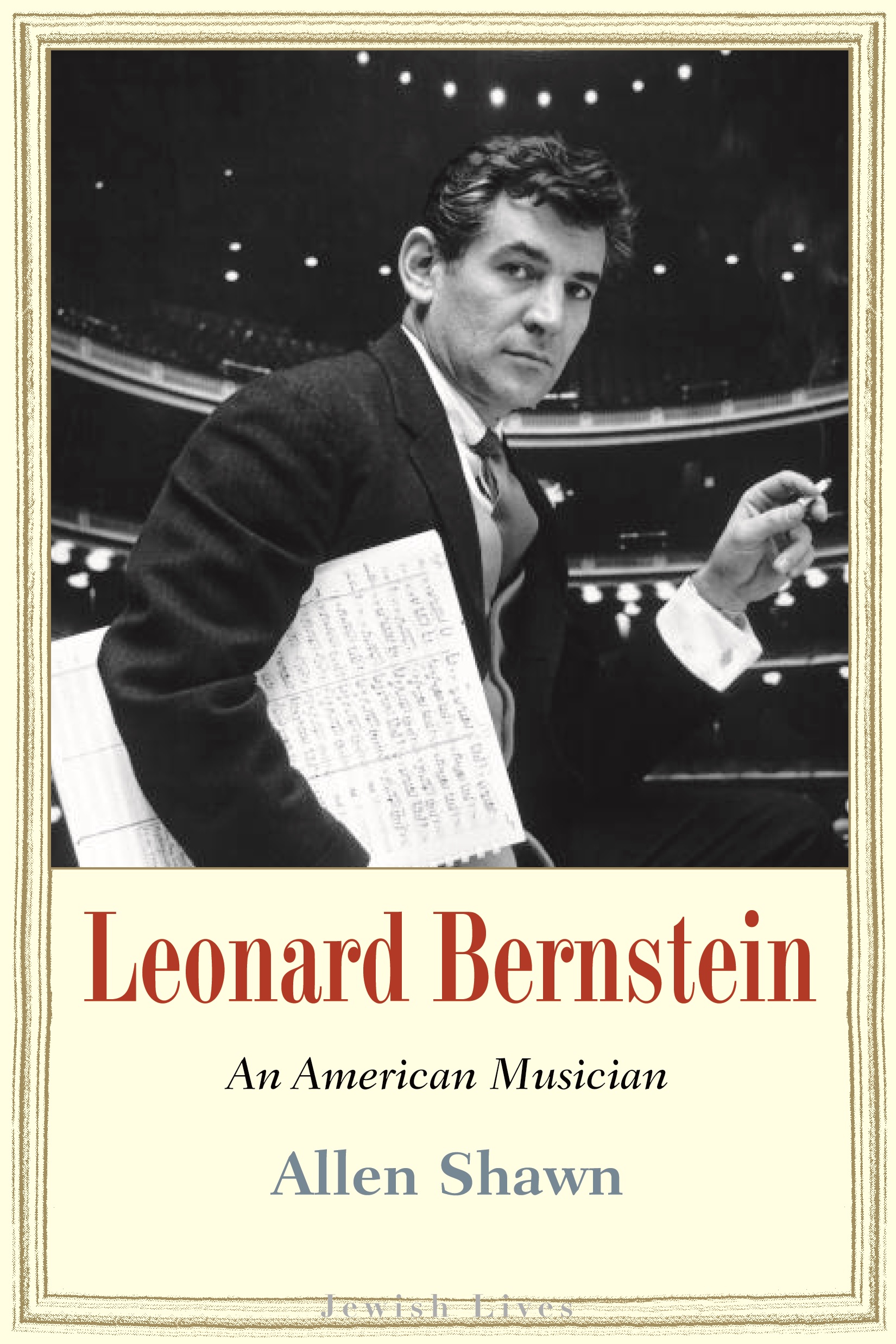

By

Franklin Bruno

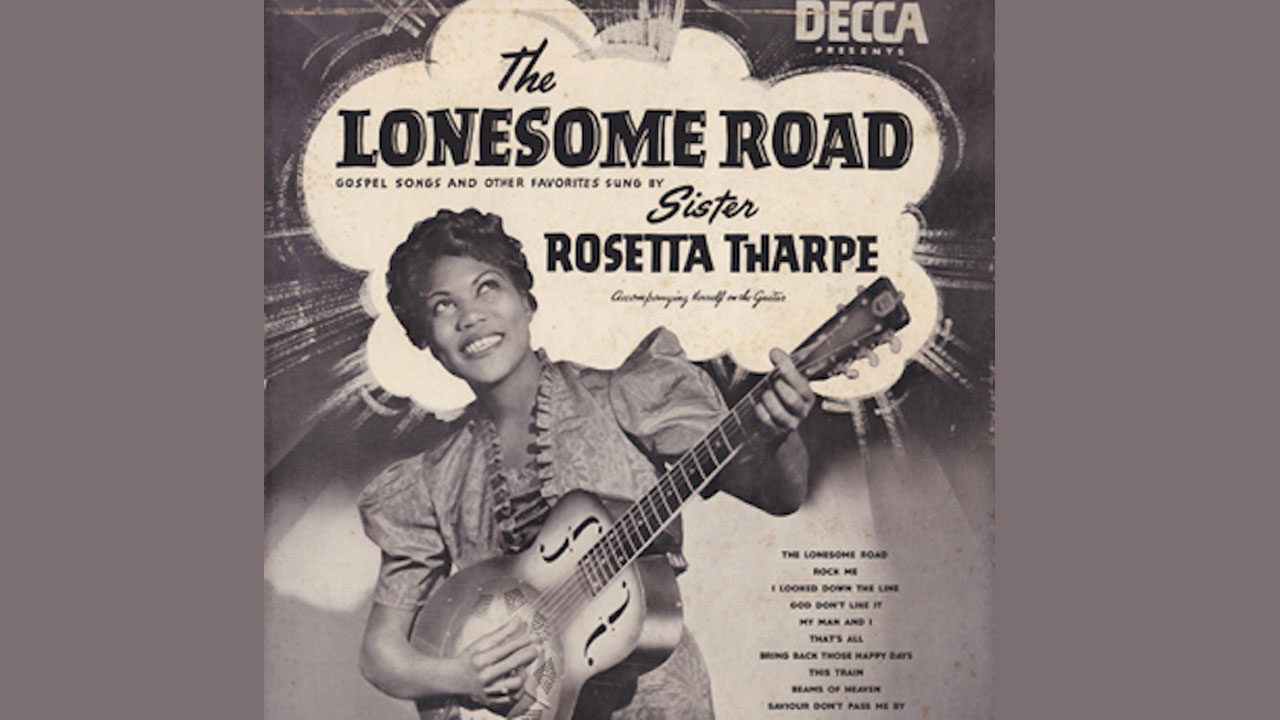

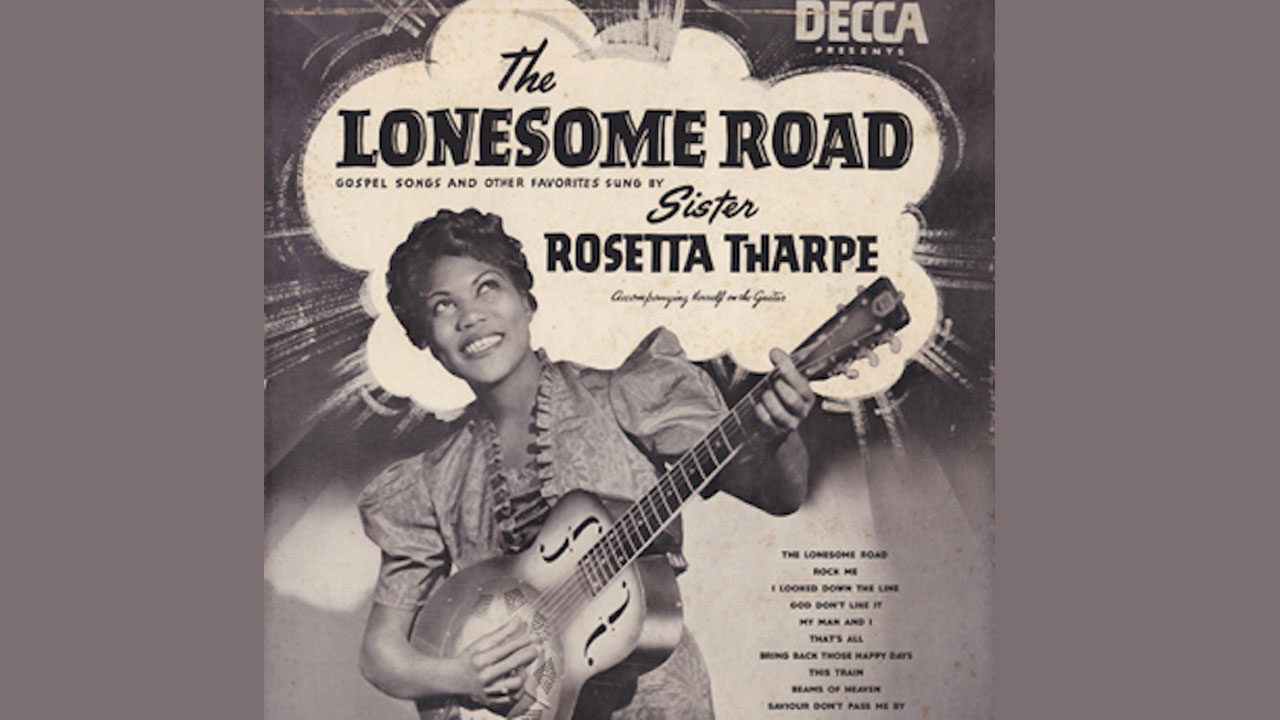

There may be songs whose histories are uncorrupted or wholly unrecoverable. “(The) Lonesome Road” is not among them. The road that everybody, including “E.V. Body,” in this story tredges on is crowded with two-way traffic: some stretches are dusty, others are paved with Tin Pan Alley gold or earnest populist intentions, and it is constantly being dug up and laid anew.

By

Dan Booth

On Twitter the entire point is that somebody is watching you. Success is measured in followers. No wonder Sly Stone never seems at home there, and never alights there too long.

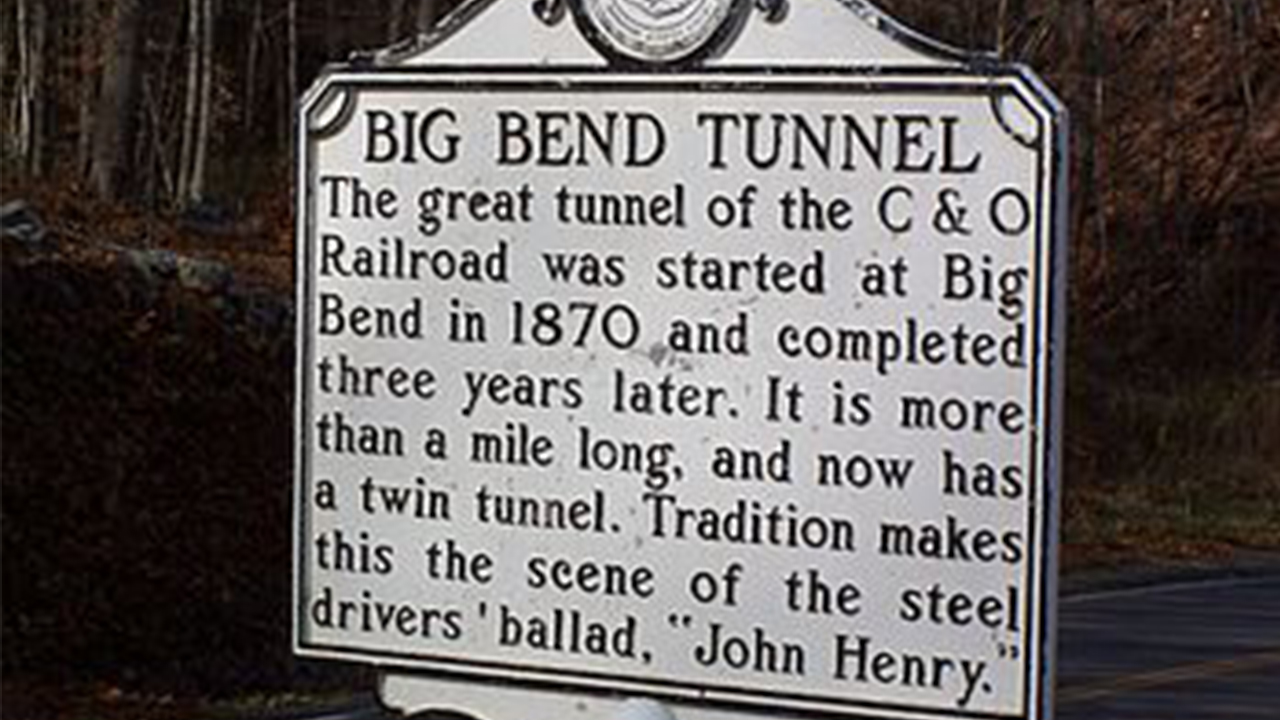

By

Jeff Rosen

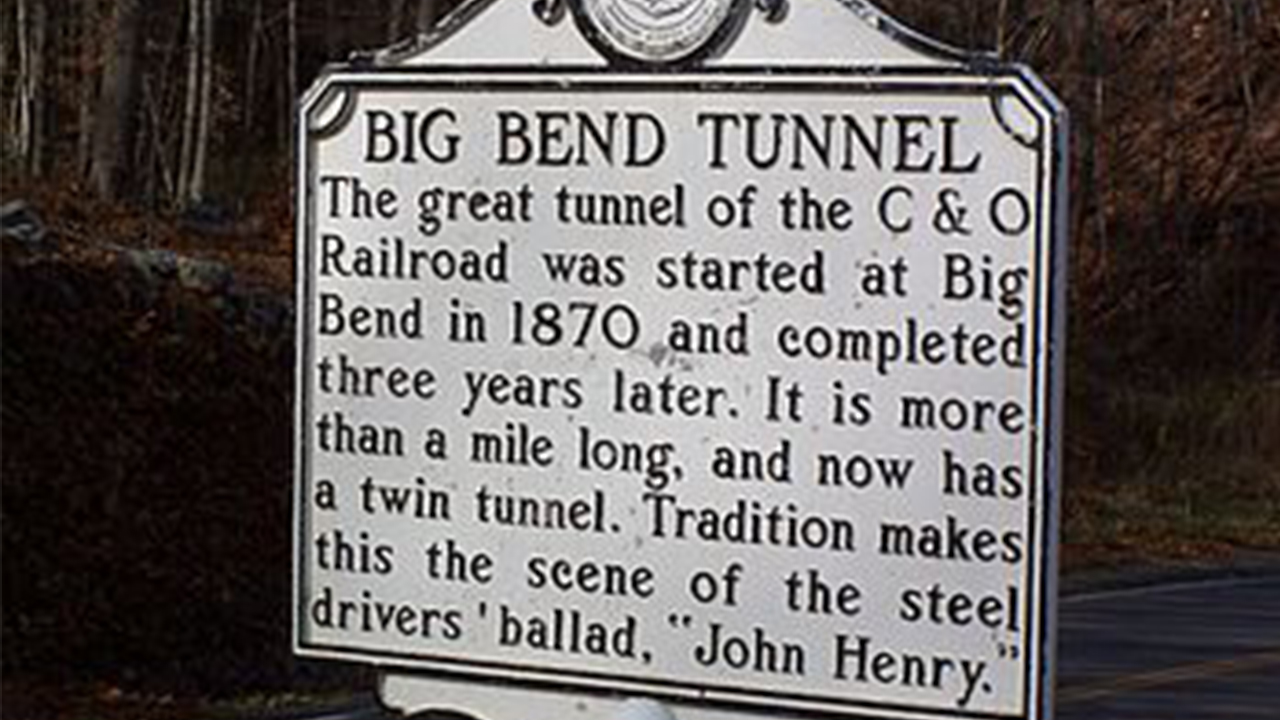

John Henry is fighting an age old battle. All of us are. Something will always come along and render us useless.

By

Gerald Early

Despite a mountain of insecurities and sheer craziness, Peggy Lee remained undaunted. Engaging, and at times challenging, she made remarkably sophisticated music well into the 1980s, refusing to be an oldies act. But perhaps her greatest claim to public attention was that the blonde, North Dakota-born singer sounded black.

By

Michele Boldrin & David K. Levine

The financial distress, or lack of distress, of musicians has nothing to do with the purpose of copyright. We, wild anti-copyright theorists, have now been joined by many sober practitioners in our analysis pointing out the real issues.

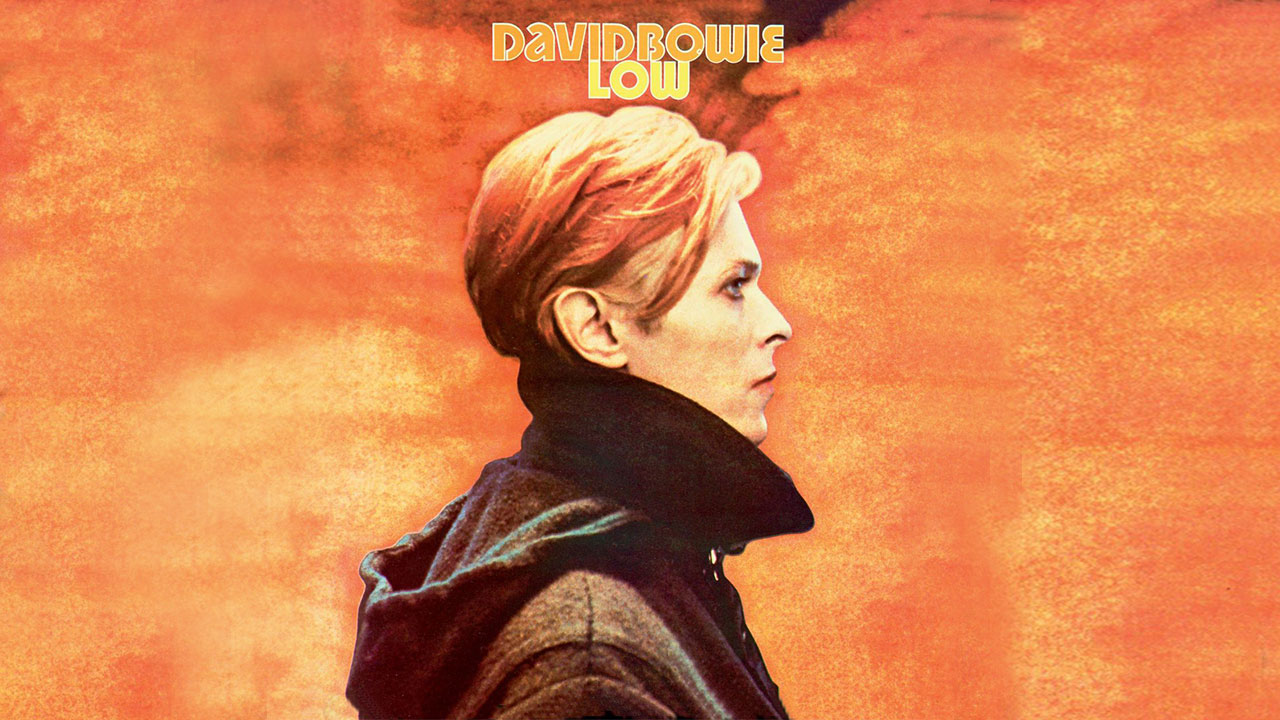

By

Ben Fulton

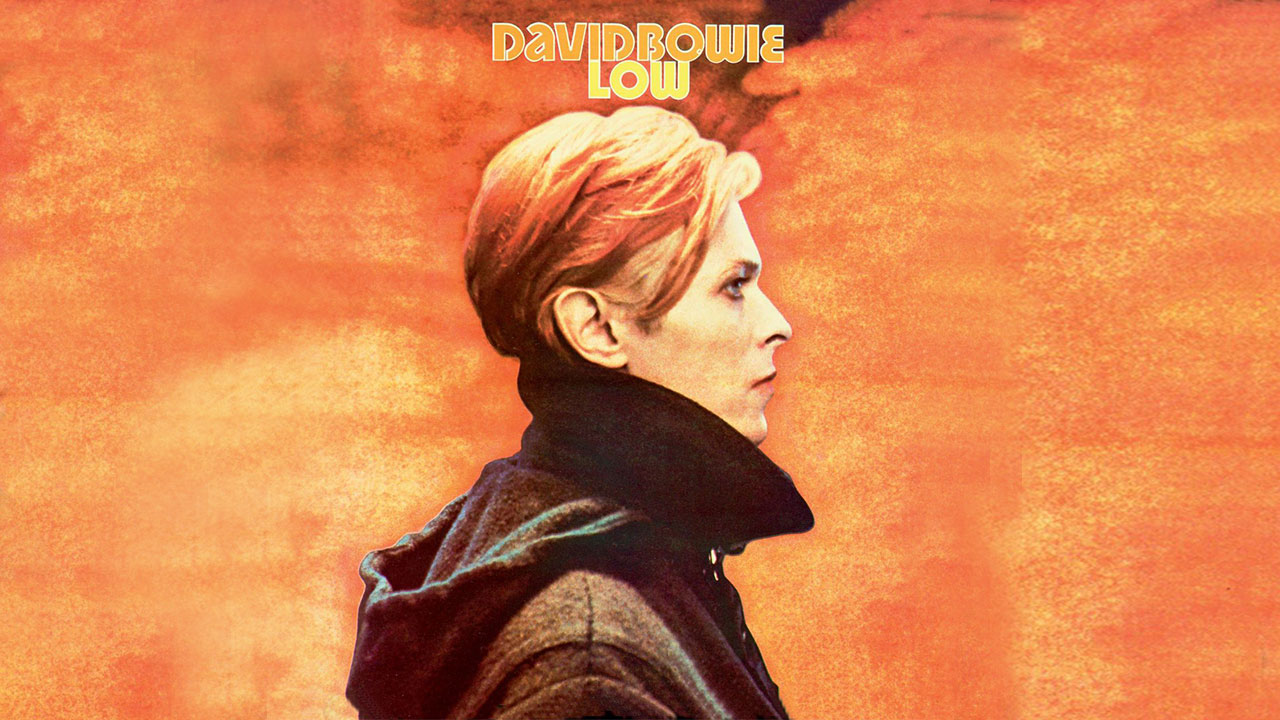

For a decade in which rock music was reaching its zenith as a profitable business, the 1970s, it is staggering to consider the sheer number of risks Bowie took, without any hint or appearance that he was risking anything at all.

By

Anthony Bolden

There was something about the music that evening, at a party in her honor, that immediately captured Bessie Smith’s attention. As she entered the party with a few of her girlfriends, Smith remarked in classic fashion, “The funk is flyin’.”