In November 2013, Greil Marcus hosted a talk and performance at the New School for Social Research by the husband-and-wife duo the Handsome Family. Rennie Sparks, who writes their lyrics, read from her book of essays Wilderness; Brett, who writes the music, joined her to play songs from their album of the same name, and Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home.” Afterwards, Brett (for the most part) answered a question about songwriting:

“Nobody who has spent any time studying music wants to write a bunch of songs that are just I-IV-V-I – diatonic songs in C. [Rennie: “Yeah, but it works.”] A big inspiration to me was going back to things that were recorded in the twenties that were […] leaderless, less full of ego. A song like “Froggie Went a-Courting,” that has two chords. [Rennie: “But they’re the right two.”] And it’s perfect. If you threw a II in there, or a turnaround or something, it would just be ridiculous.”

I have nothing against two-, one-, and no-chord songs. I have played them, and written them. And I know the Sparks’ are no naïfs: you need six to play “Far From Any Road,” which the Handsome Family licensed as the theme for HBO’s True Detective. Still: Near Union Square, where Tin Pan Alley was quartered in 1900, we were being enjoined to forgo other techniques and traditions in favor of a self-consciously reduced musical vocabulary, not just out of respect for its history, but for its perfect simplicity and elemental connection to…well, to what? The people, the land, what Mike Seeger calls “the true vine”?

This is something musicians have done at the New School for decades. In January 1930, Thomas Hart Benton completed America Today, a twelve-panel mural for the college’s flagship International Style building. At its unveiling, Benton and his students sang the painter’s favorite American songs to guitar accompaniment by Charles Seeger, a Harvard-educated composer and musicologist then teaching at the New School and the Institute of Musical Art (later Julliard). At the time, Seeger was a vocal champion of modernist composition, and a Marxist. In the early 1930s, Seeger and his classically trained colleagues in the Communist Party-sponsored Composers’ Collective had sought a proper form for “music as a weapon in the class struggle” in a forbiddingly dissonant art song style influenced by German émigré Hanns Eisler. Seeger’s conversion to folk music was not immediate, but the performance with Benton, encounters with Alan Lomax and Aunt Molly Jackson, and the CPUSA’s shift to a nationalistic Popular Front policy began to change his mind, setting a course for folk-revivalism on the intellectual Left. The notion of writing new “folk” songs with class-conscious, topical lyrics only took hold with Woody Guthrie’s arrival in New York in 1940. Guthrie gave revivalist and Popular Front aesthetic principles homespun expression, attacking the products of Broadway and Hollywood as “dying songs—the ones about champagne for two and moon over Miami,” asking “Is Tin Pan Alley a full-blooded American?”, and warning Seeger’s son Pete, another convert, not to play “fancy chords” behind him.

From what I heard at the New School, the Sparks are more drawn to Harry Smith’s esoteric vision of folk music than the Seeger/Guthrie/Lomax agitprop line. But their comments reflect a scale of musical values, now unhitched from its political moorings, first proposed in the 1930s and 1940s. Its main elements include: avoidance of formal and harmonic elaboration; suspicion of urban and commercial influences; and appeals to “roots” or “rootedness” that often mask a measure of nativism. That these were once ideas of the Left is less important, for my purposes, than recognizing that they are ideas at all, whether stated in Guthrie’s “professional Okie” voice, the introduction to “Bob Dylan’s Blues,” or Rennie Sparks’ identification of “the right two” chords. Whether or not they are correct, they are not self-evident.

• • •

We can glimpse another road, less untaken than unmapped, by looking to the period just before Charles Seeger and others set forth for Damascus. In 1927—the year of Show Boat, Louis Armstrong’s Hot Seven sessions, and Ralph Peer’s “discovery” of The Carter Family and Jimmie Rogers in Bristol, Tennessee—two versions of a song called “Lonesome Road” or “The Lonesome Road” appeared. One was recorded by Gene Austin, its credited lyricist, with music by Victor Records’ house arranger and bandleader Nathan Shilkret. The record and sheet music were sizable hits, though not Austin’s biggest. Their song replaced “Ol’ Man River” in the first film version of Show Boat (1929), and has since been performed by artists from Sam Cooke and Stevie Wonder to Frank Sinatra and the Delmore Brothers. [1]

Greil Marcus writes that Austin’s recording is “filled with specters from the oldest Appalachian ballads.” He has never played it “for anyone …who didn’t drift off to another place while listening or who failed to say, ‘What was that?’ when it was over.” Gayle Wald’s biography of Sister Rosetta Tharpe takes the song itself for “a blues she sang in a Sanctified style,” without delving into its origins. Alfred Appel Jr. dismisses it as a “pseudo-spiritual” with “shallow ‘sacred’ lyrics,” of interest only for its parodic dismantling by Louis Armstrong. Andrew Berish threads the needle: “The journey of ‘The Lonesome Road’ is a familiar one in American popular music: a black vernacular song adopted by white musicians and transformed into an ersatz popular ‘folk’ tune that in turn becomes reappropriated by black artists for the commercial market.” Berish is probably right about the song’s African-American origins; the isolated black prisoners who sang “Look Down That Long, Lonesome Road” for John and Alan Lomax in South Carolina in 1934 betrayed no awareness of the commercial adaptation. That said, the pop version’s impurities, adopted by many black and white performers, have been crucial to its flexibility and longevity.

Greil Marcus writes that Austin’s recording is “filled with specters from the oldest Appalachian ballads.” He has never played it “for anyone …who didn’t drift off to another place while listening or who failed to say, ‘What was that?’ when it was over.”

Another “Lonesome Road” (without “The”) was a scored piano-vocal arrangement, or recomposition, by the American composer Ruth Crawford, several years before she met and married Charles Seeger. It was first published in Carl Sandburg’s The American Songbag, at the time the most widely read collection of its kind. Despite renewed interest in Crawford’s music and later career as a transcriber, editor, and theorist of American folk song, her treatment of the material remained unrecorded until 2005. Though one version of “(The) Lonesome Road” was presented (and copyrighted) as an original popular song and the other intended to represent an extant folk song, both altered their source material as their makers saw fit, and neither is easily mistaken for a transparent transmission of vernacular musical values. As of 1927, neither Austin and Shilkret nor Crawford took latter-day folk-revivalism’s ethos of inviolable simplicity as their North Star.

• • •

“Lonesome” is a Standard English variant of “lonely,” found in print since the 17th century, and in black spirituals since “Lonesome Valley,” printed in Slave Songs of the United States in 1867. The phrase “lonesome road” first appeared in a published song lyric in Howard Odum’s landmark article “Folk-Song and Folk-Poetry as Found in the Secular Songs of the Southern Negroes” (1911). A song Odum titles “I Love That Man,” collected in Georgia and “ordinarily sung as the appeal of a woman,” ends with these stanzas:

Look down po’ lonesome road

Hacks all dead in a line

Some give nickel, some give dime,

To bury this poor body of mine.

The hacks are funeral carriages; we are not far from “St. James Infirmary.” Repeat signs indicate that each stanza was sung twice. John Lomax included the “hacks” stanza in “Self-Pity in Negro Folk-Songs,” a 1917 essay for The Nation, as evidence that “the negro is moved by pictures of himself and his loved ones dying”—not, one would think, an exceptional response. Odum and Guy Johnson reprinted the song in several later books; in 1927, white dramatist Paul Green used a text close to Odum’s, now titled “Look Down that Lonesome Road,” in his Pulitzer-winning black dialect play In Abraham’s Bosom.

These writers’ main interest was in the black folk lyric. An early variant with a notated arrangement appears as “Dat Lonesome Road” in Francis Abbot and Alfred Swan’s Eight Negro Songs from Bedford County, Virginia (1924). Its five-line stanzas differ from the version Odum collected, and the tune incorporates a jarring chromatic melisma, reproduced on record by John Jacob Niles (1956) and Paul Clayton (1962). Peggy Seeger’s 1955 Folkways recording (“Long Lonesome Road”) is a Guthriesque simplification of this material, with additional “migratory verses,” per her father Charles’ liner notes, from “other such songs.” This is the model for commercial folk recordings by Joan Baez (1961), Ian & Sylvia (1964), and others.

“Lonesome” is a Standard English variant of “lonely,” found in print since the 17th century, and in black spirituals since “Lonesome Valley,” printed in Slave Songs of the United States in 1867.

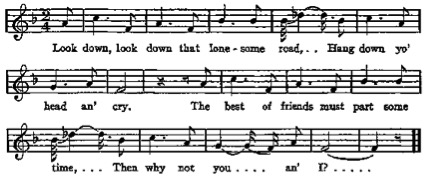

Of pre-1927 publications, Austin and Shilkret’s song most resembles one in Dorothy Scarborough’s On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs (1925), “taken down from the singing of Charles Galloway, a black man, uneducated, a worker on the roads” by one Evelyn Cary Williams. Williams taught piano and music theory at Randolph-Macon Women’s College in Lynchburg, Virginia, and collected local variants of Child ballads for the Virginia Folklore Society. In her transcription, “The Lonesome Road” became a two-stanza common meter ballad:

Look down, look down that lonesome road,

Hang down your head and cry.

The best of friends must part sometime,

Then why not you an’ I?

True love, true love, what have I done,

That you should treat me so?

You caused me to walk and talk with you

Like I never done befo’.

This text and tune reflect what Williams could hear and notate, as much as what Galloway sang. Like the dialect spellings, the rising slurs on “ro-ad” and “ti-me” are meant to approximate black vernacular singing. They rise from the fourth scale degree to a flatted or minor sixth—the tune’s melodic peak, and only deviation from the major scale. These are not orthodox “blue notes”—the flatted thirds and sevenths found in popular sheet music since W.C. Handy’s 1914 score for “Saint Louis Blues.” Accurate or not, the unusual “ro-ad” interval marks “The Lonesome Road” as a particular song, distinct from others. You could even call it a hook.

• • •

No paper trail leads from Galloway and Williams’s song to Austin and Shilkret’s, but several lines are identical, as are the pitches and melodic rhythm of the first eight measures. Who were these New York song thieves? Gene Austin was born Lemuel Eugene Lucas in Gainesville, Texas in 1900 and raised in Yellow Pine, Louisiana. According to his posthumous (and often fanciful) memoir Gene Austin’s Ol’ Buddy, he absorbed cowboy songs growing up near the Chisholm Trail, ragtime piano from whorehouse “professors,” and work songs and spirituals in Yellow Pine’s black quarter. Much of the book centers on Austin’s friendship with “Uncle Esau,” a kindly sharecropper – in effect, a Magical Negro – who encourages his ambitions (“Ef’n yes feels yes has a real talen’ fo’ singin’, yes mus’ follow yew soul’s call”) but warns, “Boy, yo’ got a lonely road tuh travel.”

From 1925 to 1929, Austin was Victor’s reigning male vocalist, introducing or popularizing such standards as “Ain’t She Sweet” (Ager-Yellen), “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” (Donaldson-Kahn), and 1927’s multi-million-selling “My Blue Heaven” (Donaldson-Whiting). His singing, though less intimate than that of the 1930s crooners who displaced him, was conversational for its time, neither stiff and quasi-operatic nor ostentationsly “hot.” Earlier, however, Austin sang with George Reneau, a blind street guitarist from Knoxville, Tennessee, on “old-time” records marketed to rural whites. As the Blue Ridge Duo, they cut over forty sides for Edison and Vocalion in 1924-1925, from Thomas Hart Benton’s beloved “Cindy” and “Ida Red” to “Red Wing” and “Jesse James.” Their “Lonesome Road Blues” is a spirited rendition of “Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad,” which Woody Guthrie would adopt as his radio theme, suggest to the producers of John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, and rework as a Dust Bowl ballad more than a decade later.

Nathaniel (“Nat”) Shilkret was born in New York to Ukrainian Jews in 1889. As a clarinet prodigy, he performed in Yiddish theater and with an orchestra of boys “from East Side Jewish and Italian families” who toured as far as New Orleans. In 1915, Victor hired him to manage the label’s Foreign Department, where he recorded everything from cantorial services to folk songs in Greek, Finnish, and multiple Slavic dialects. As Victor’s Director of Light Music in the 1920s and 1930s, he presided over sessions with Enrico Caruso, John MacCormack, and the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and appeared on hundreds of 78s by the Victor Salon Orchestra.

Shilkret also helped invent country music. To compete with Henry Whittier’s 1923 recording of “The Wreck of the Old 97” on Okeh, Shilkret asked Vernon Dalhart, a trained light-opera singer from Texas, to re-record it for Victor. As the flip side, Dalhart suggested “The Prisoner’s Song,” which his cousin Guy Massey had written, or heard, in jail. (A similar song was collected in Missouri around this time; The Carter Family’s “Meet Me in the Moonlight” is from the same family.) Shilkret liked the words but not the tune, wrote a new one in waltz time, and arranged it for Dalhart, guitarist Carson Robison, and Victor violist and concertmaster Lou Raderman, but forewent writing credit. After “The Prisoner’s Song” became the first million-seller in this style, Shilkret made his own song-catching trip through Virginia and West Virginia, where one persistent fiddler tried to sell him “Yankee Doodle.” Ralph Peer, the enterprising record man Shilkret hired in 1927 to scour the South for unrecorded singers and uncopyrighted songs, proved more successful.

• • •

Austin recorded “The Lonesome Road” at Victor’s Camden, New Jersey studios on September 16, 1927; it was released the following February. Shilkret’s simple instrumentation reproduced well in the still-new medium of electrical recording: piano, a viola counterline by that down-home fiddler Lou Raderman, and—for short passages—harp and orchestra bells. Austin’s vocal is unhurried, even grave; on some reprises, he hums or whistles the main strain. Singing in his lowest register, Austin gives deep resonance to longer vowel sounds, and drops his gs (“totin’, “tredgin’”) and rs (“befo’ you travel on”). This is not comic minstrelsy, but it is Austin’s version of singing black: if there is any doubt, compare “The Lonesome Road” with his recordings of “My Blue Heaven,” or even Fats Waller and Andy Razaf’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” which many contemporary audiences would sniff at as “lily-white.”

An uncredited song doctor also had a hand in the revision. Sam Coslow, born in New York in 1902, was a purer product of Tin Pan Alley than Austin or Shilkret. (Guthrie, citing “dying songs” about “champagne for two,” misremembered Coslow and Arthur Johnston’s “Cocktails for Two.”) In 1927, Coslow had just ventured into music publishing with plugger Larry Spier. According to his autobiography,

“Nat and Gene … had just revised and dressed up an obscure old spiritual which they wanted to record, but Nat felt that something was wrong with the lyric. … I knew they were offering us a hit as soon as Gene sang: “Look down, look down—that lonesome road. … They were right, however, about the need of a little doctoring up. The song seemed too long and it ended rather awkwardly. The lyric had a couple of faulty rhymes, and the promise in the striking opening phrase lacked a punchy follow-through. Nat quickly dashed off a lead sheet and left it with me. I locked myself in one of our tiny piano studios and spent the rest of the afternoon doing the necessary surgery. Nat and Gene came back the next day and proclaimed the operation a success.”

Folkloric accuracy was not a consideration. Standing to profit as publisher, Coslow “never added [his] name as a co-author or cut in on the writers’ royalties, though I could have legitimately asked their permission to do so.”

Assuming Scarborough’s publication as their starting point, we can ask: what operations did Nat, Gene, and Sam collectively perform? First, they harmonized an unaccompanied melody in F major. The main (or A) strain employs three chords: F, C7, and—where one expects the subdominant B-flat major—a chromatically altered B-flat minor. There is no blueslike major-minor ambiguity here: the chord’s out-of-key D-flat simply reinforces the distinctive flatted sixth of “ro-ad.” Second, the professionals added an eight-measure bridge, turning Williams’ ballad into a 32-bar AABA song—the dominant commercial form from the mid-1920s to roughly 1950, and the very monogram of homogeneity and triviality for folk purists. The first chorus, with the bridge in boldface, runs:

Look down, look down that lonesome road,

Before you travel on.

Look up, look up, and seek your maker,

‘fore Gabriel blows his horn.

Weary totin’ such a load,

Tredgin’ down that lonesome road.

Look down, look down that lonesome road,

Before you travel on.

Like the A strain, the bridge involves three chords: D-minor, A-minor, another D-minor, and, at “road,” the dominant C7, which resolves to the tonic F in the usual way. This detour through the relative minor is barely a modulation, in that it never leaves the notes and chords available in F major. The entire song uses five chords; listeners may judge whether the result sounds “fancy” or “ridiculous.”

While these additions read as pop today, there are further generic subtleties. Features of “The Lonesome Road” resemble arrangements of the spirituals “Deep River” and “Go Down, Moses” published in 1916-17 by Harry T. Burleigh, one of the most respected black musicians of his day. “Deep River” also has a contrasting middle section (unlike the Fisk-era text it is based on), and Burleigh’s setting of “let my people [go]” is a rhythmic match for a four-note piano figure that runs throughout Shilkret’s arrangement, though the pitches are different. In the bridge, “weary totin’” and “tredgin’ down that” are sung to the same rhythm. In the 1920s, arrangements like Burleigh’s were core repertoire for such black recitalists as Roland Hayes, Jules Bledsoe, and Paul Robeson, and Shilkret surely knew Marian Anderson’s historic 1923-1924 Victor recordings of both songs.

Jerome Kern also knew Burleigh’s music: he had been a frequent guest singer at Kern’s grandfather’s synagogue. Musical theater scholar Todd Decker calls “The Lonesome Road” a “shadow hit” derived from Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s “Ol’ Man River,” and the songs share several details—notably, the “let my people” motif—but the actual relationship between them is unclear. It is possible that Shilkret or his collaborators had already heard the score to Show Boat, but their song was recorded, and thus written, well before the musical’s Broadway premiere in December 1927 and the first released recordings (on Victor) of “Ol’ Man River” the following month. The published record leaves the mystery open, though Shilkret’s comment that using “The Lonesome Road” in the early Show Boat film was “practically asinine” suggests a twinge of guilt. Whatever the truth, both pseudo-spirituals trade on the then-respectable but not precisely pop genre of the “concert spiritual,” and on signifiers of musical blackness less audible in the wake of modern gospel, rhythm-and-blues, and soul.

Shilkret, Austin, and Coslow also gave the lyrics religion. In any version, the song’s central road image evokes the Exodus narrative that has encoded black mobility from the time of the Underground Railroad through the Great Migrations and beyond. That said, the Creator (“maker”) is absent in the published folkloric texts: these are not songs of spiritual striving or reconciliation, but bitter, worldly ones of failed love and parting. Nor were Gabriel and his horn part of “The Lonesome Road” before it reached New York City. Again, the image is prominent in 19th-century spirituals (“Blow Your Trumpet, Gabriel”), and in God’s Trombones (1927), James Weldon Johnson’s tribute to Southern black preaching. Coslow’s presumption that a solemn, black-sounding song must be an “obscure old spiritual” suggests some such inspiration. This was cosmetic surgery: the pop version’s second chorus makes only slight prosodic adjustments to Williams’ “True love, true love” strophe before reprising the bridge and opening lines: this half of the song contains no spiritual imagery at all.

• • •

Many later recordings of “The Lonesome Road” are simply renditions of the underlying song, rather than covers, in the rock-era sense, of the 1927 recording. Most omit the “let my people” instrumental figure, as does Austin’s own Western Swing-styled remake, recorded as a medley with “This Train” in 1947. Some notable interpreters, however, have signified on the original. On Louis Armstrong’s November 1931 recording, the song is a pretext for a travesty of a black church service. “Reverend Satchelmouth” barely touches on the lyrics beyond the first and last lines, as he introduces members of the fictive congregation and passes the collection plate. After a trumpet solo over the A strain, he counts the take: “Two dollars more would have gotten my shoes out of pawn. But nevertheless I’m in love with you!” Another voice has the last word: “Bye-bye, you vipers!” This is also a stoner record, cut under the influence of Armstrong’s daily “gage.” Never known for piety, Armstrong relished depicting religion as a grift, but one wonders if he would have done so against the background of a song with a less compromised pedigree. (Armstrong did play the melody straight on at least one much later occasion.)

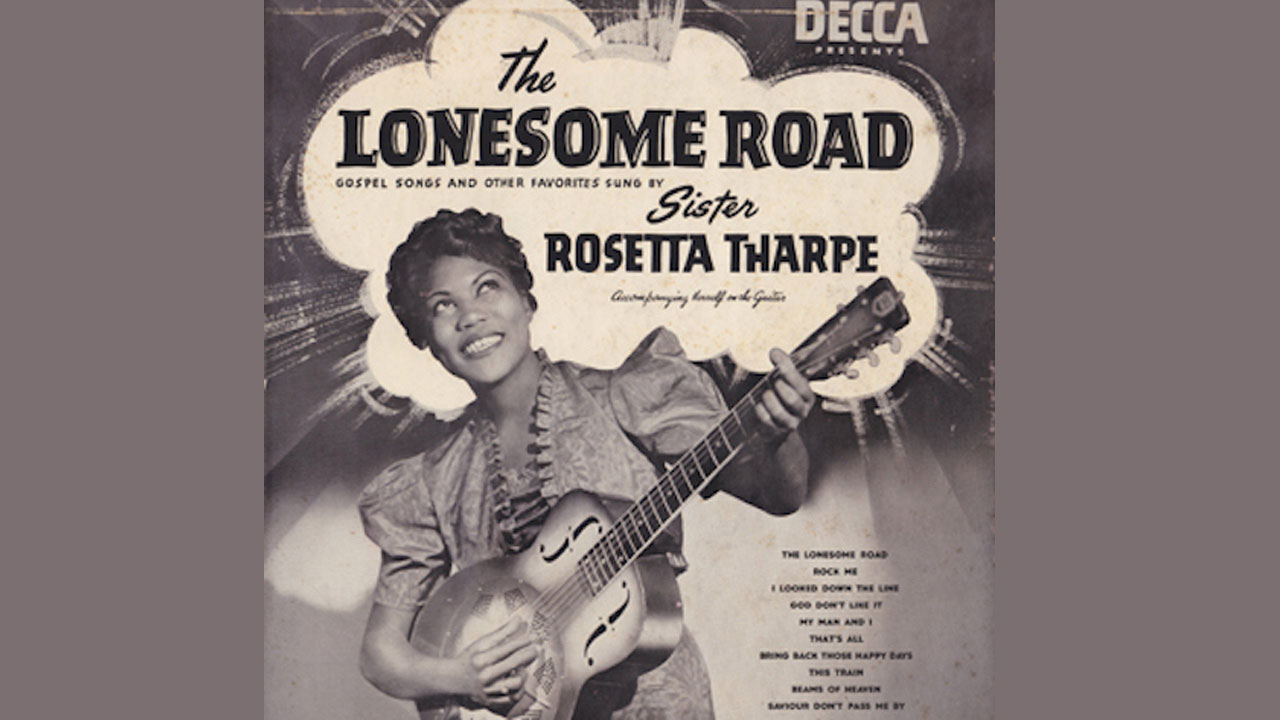

Sister Rosetta Tharpe seemingly meant “The Lonesome Road” to be taken as gospel when she sang it, to her own acoustic guitar accompaniment, for her first Decca Records session in 1938. She swung it as girl singer with Lucky Millinder and his Orchestra in a 1941 “Soundie” (made for an early line of video jukeboxes), standing apart from the leggy black Lindy hoppers who add a taste of cheesecake. In a 1961 performance, fronting a band of English trad jazz players on the European folk-blues-gospel revival circuit, Tharpe gesticulates, plays fiery electric blues fills, and arguably oversings. If this is church, it is also theater. Tharpe made the song her own, but what she made her own was its pop revision. Austin and Shilkret’s writing credits appear on the Decca release, on which Tharpe sings both the semi-religious chorus and the tellingly secular one. For all her gospelized melodic and rhythmic liberties, Tharpe usually retains the distinctive “ro-ad” interval, and always sings—and, in 1938 and 1961, solos over—both the A and B sections, like a jazz performer playing a standard. Most of Tharpe’s repertoire stood on one or the other side of the divide between gospel and rhythm-and-blues. “The Lonesome Road” was the rare song that encouraged her to straddle it. Tharpe, like Armstrong, seems to have understood that it was no pure product of black folk, much less of the black church, and as such no object for undue reverence.

As Sean Wilentz and others have noted, Austin’s recording is the template for “Sugar Baby,” the closing track on Bob Dylan’s “Love and Theft” (2001). The entire album drinks deeply from streams of American music Dylan’s early idol Woody Guthrie would rather have dammed up; several songs (“Bye and Bye,” “Floater,” “Moonlight”) are sung over the changes of 1930s standards. In the case of “The Lonesome Road,” Dylan undoubtedly recalled strophic versions sung by his one-time revivalist colleagues Paul Clayton and Joan Baez, but the music he uses is pointedly that of the pop-spiritual, with Shilkret’s instrumental figure transferred from piano to tremeloed guitar. “Sugar Baby” is not, of course, a cover in the usual sense. Dylan alters the rhyme scheme and prosody to accommodate new lyrics, while retaining the song’s melodic arc and AABA form. These 32-bar units alternate, five times in all, with a chorus (beginning “Sugar Baby, get on down the road, you ain’t got no brains nohow”) related to similarly titled recordings by Dock Boggs and Mance Lipscomb. Dylan does not always mark a trail back to his points of departure; here, he does. He never sings the words “lonesome road,” but his last verse paraphrases the “true love, true love” stanza, and the only line he quotes in full comes not from folklore but fakelore: “Look up, look up—seek your Maker—‘fore Gabriel blows his horn.” [2].

• • •

As of 1927, Ruth Crawford knew less about traditional American music than some contemporaries in the commercial recording industry. The daughter and granddaughter of Methodist circuit riders, Crawford was born in 1901, in East Liverpool, Ohio. A serious piano student, she moved to Chicago in 1921 to attend the American Conservatory of Music, a path that might have ended in a teaching career like Evelyn Cary Williams’. Crawford soon turned her attention to composition, writing to her mother that “it seems so wonderful to discover some new chord which will make more variety; and it is so interesting, the composing of one’s own melodies, I just love it.” By the mid-1920s, she was one of a coterie of self-styled “ultramodern” composers who combined extensive chromaticism and dissonance with a mystically-tinged methodology. Her compositions were performed, published, and respected by such colleagues as Henry Cowell and Aaron Copland. In 1930, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first given to an American woman composer.

In 1926, Carl and Helga Sandburg hired Crawford as their daughters’ piano teacher. At the time, Sandburg was expanding The American Songbag from its privately printed first edition, made up of songs collected informally at readings, in melody-only transcriptions by Alfred Frankenstein. His trade publisher requested full piano-vocal arrangements, so the book could be played from as well as read. When Frankenstein declined the assignment, Sandburg split it among sixteen Chicago composers, including Crawford. Sandburg’s unscholarly compendium of 280 “real American songs” tellingly contrasts with later representations of folk repertoire. His expansive introduction mounts no jeremiad against jazz or popular music, and avoids anti-urban rhetoric, promising “a volume … as modern as skyscrapers, the Volstead Act, and the latest oil-well gusher. … People of lonesome hills and valleys are joined with ‘the city slicker’ in the panorama of its pages.” Despite Sandburg’s contact with socialist and radical labor groups, the book’s politics are muted. He includes Joe Hill’s “The Preacher and the Bear,” and numerous occupational songs, but none of the militant Wobbly strike songs he must also have known. Class-consciousness is implicit, but not yet weaponized, as it would be by Alan Lomax, Lawrence Gellart and other editors from the 1930s on.

Nor were simplicity and non-literacy the watchwords they would become. The book’s “elaborate and accomplished harmonizations” by professional musicians were meant to be a selling point. Crawford’s biographical note duly lists her conservatory training and previous works. Of her four arrangements, “Lonesome Road” is the most distinctive. (The others are “There Was an Old Soldier,” “Ten Thousand Miles Away from Home,” and “Those Gambler’s Blues,” a variant of “St. James Infirmary.”) Falling outside the book’s selection of spirituals, it is classed as a secular song of probable black origin taken up by white singers in the South and Midwest. Sandburg’s headnote frames it, per John Lomax, as “a cry of self-pity and a hymn of personal hatred.” Of two texts, Crawford arranged “‘Lonesome Road’ as it came to Pendleton, Indiana, to people who passed it on to Lloyd Lewis”:

Look down, look down that lonesome road,

Hang down your head and sigh.

The best of friends must part some day,

So why not you and I?

So why not you and I?

I wish to God that I had died,

Had died ‘fore I was born,

Before I heard your smilin’ face

An’ heard your lyin’ tongue

An’ heard your lyin’ tongue

Crawford did not learn the song from a first-hand vernacular performance or field recording; she may have worked from Sandburg’s singing or a sketch by Frankenstein. Her published melody, in ¾ time, is entirely diatonic, with smaller intervals between pitches than Williams’, until the ornamental slurs that end each strophe: “So why-i, not you-oo, and I?” The piano part, while not difficult to play, reveals Crawford’s sophistication, moving out of the home key at “lonesome,” ending phrases on distant minor chords, and resolving only at the end of the second strophe. The voicings at “The best of friends must part some day” are richly chromatic, and a countermelody under the the first “you and I” (and “lyin’ tounge”) borders on naked dissonance. Though less “ultramodern” than Crawford’s piano and chamber music, this goes well beyond ordinary folk, blues, or even pop harmony. Her biographer Judith Tick judges the piece “overburdened by technique,” while affirming that it “reflects her emotional response to the material as personal rather than social document.”

Outside of later editions of The American Songbag, I have seen only one republication of Crawford’s work: it came to me by accident, in a sheaf of musty sheet music from my uncle Anthony DiTomasso’s piano bench. The Joe Davis Folio of Carson J. Robison Songs (1930) is a seventy-five cent, octavo collection of fifty “Hill Country Ballads and Old Time Songs”—commercial designations for rurally-styled music before “hillbilly,” and then “country,” became the industry standard. Joe Davis, who cut himself in for credit on Fats Waller’s early songs, was one of Tin Pan Alley’s less scrupulous mainstays; we have already encountered Carson Robison, whose name was meant to sell the book, as the guitarist on “The Prisoner’s Song.”

Most of the folio’s contents, from “Barbara Allen” to “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers,” were drawn from the public domain, credited to “E.V. Body,” and copyrighted by Davis’ Triangle Music, operating from a Broadway address two blocks south of the Brill Building. “Lonesome Road,” assigned the same pseudo-anonymous writing credit, is merely a fresh engraving of Crawford’s score, with trivial notational alterations. This may have been legal thievery: The American Songbag does not indicate the copyright status of individual selections. The Austin-Shilkret version was still popular in 1930, thanks to the recent Show Boat film and newer recordings by Shilkret and bandleader Ted Lewis. Joe Davis could not publish that song with impunity, but buyers might have thought it was what they were getting, until they sat down at the piano.

In the 1980s, Larry Polansky composed The Lonesome Road (Crawford Variations), a cycle of fifty-one miniatures based on complex transformations of Crawford’s piano part. To my knowledge, the song’s only recording as a song appears on Parades and Panoramas (2005), an exploration of the Songbag by Dan Zanes and a large supporting cast. Zanes’ liner notes comment that some of arrangements in Sandburg’s book “felt more elaborate than the tunes could bear … but this one was too perfect to change in any way.” The recording is not quite true to this description. A stand-up bass doubles the left hand, and Zanes takes a guitar solo after the second strophe. Cynthia Hopkins’ piano-vocal performance is accurate, if mannered; the piano itself is tinny and noticeably out of tune, as though Crawford had meant to score a saloon scene from Gunsmoke. Despite this shabby-chic affectation, Parades and Panoramas is the best available guide to Crawford’s contribution, short of opening The American Songbag and playing it yourself.

• • •

Crawford’s contact with “American stuff” remained casual until the 1930s. Her diary of October 1929 recorded the novelty of a concert in Washington D.C. that included “Negro exultations and Kentucky Mountain Songs” by John Jacob Niles and performances of “St. Louis Blues” and “A Paraphrase of Three Negro Spirituals” by Nathan Shilkret and His Chamber Orchestra. The same year, through Henry Cowell, she began private composition lessons with Charles Seeger, who allowed her to audit an early meeting of the all-male American Musicological Society—through a closed door. After a productive Guggenheim year in Berlin and Paris, where Seeger joined her, they married in October 1932. (Pete Seeger was Charles’ son from his first marriage; his and Crawford’s first two children, Michael and Peggy, were born in 1933 and 1935.) In this period, Crawford struggled with and abandoned an extended orchestral work. Seeger later informed their children that “women can’t compose symphonies.” She attended meetings of the Composers’ Collective in its Left-modernist phase, and set texts by Chinese dissident Hsi Tseng Tsiang in an anti-lyrical style that accorded with the group’s conception of “proletarian music.”

With the folk turn of the mid-1930s, Crawford immersed herself in “American stuff.” In her hands, the movement’s political impulse became an analytical one. As an expert transcriber of the Lomaxes’ field recordings, she extended conventional notation to capture the microrhythms and pitch variations of vernacular performance. Her theoretical treatise The Music of the American Folk Song (1937-1941) does not pretend that perfect transparency is possible, but consistently espouses editorial self-erasure. Her arrangements for the Lomaxes’ Our Singing Country (1941) and Folk Song U.S.A. (1947), while sacrificing some scholarly precision to utility for a lay audience, aspired to an authenticity that American Songbag did not. In a foreword to Folk Song U.S.A., Crawford and Seeger explain that “Traditionally, few chords are required to accompany any song. Secondary triads and sevenths are rarely heard, and their use should not be risked by amateurs unfamiliar with folk practice, if any connection with the original spirit of the song is to be maintained.” Or, as Guthrie would have had it, “no fancy chords.”

The documentary impulse was also, in part, a penitent one. Crawford later regretted “having set” the songs in American Songbag “as she had [because] the folk song element got lost,” and remarked that, at the time, “my mind was on the fact that I was going to have a composition in print.” Her unharmonized transcription of “Look Down That Lonesome Road” in Our Singing Country corresponded, as nearly as staff notation allowed, to the Lomaxes’ 1934 prison recording. A headnote acknowledges, not quite accurately, that “The popular version is copyrighted by Nathaniel Shilkret, N.Y., 1928,” but her previous history with the song goes unmentioned. Crawford also put her own composition aside for two decades. After 1932, her only completed work not tied to revivalist projects was the 1952 Suite for Wind Quintet, a prize-winning eleven-minute piece in her earlier style. While writing it, Peggy Seeger recalled, her mother was “almost like a new person; it was almost like a new life.”

Between Crawford’s contribution to folkloric study and her roles as a teacher, mother, and homemaker, little time was left for other creative work, but there is more than this to her later silence. Charles Seeger may have been a Marxist, but he was no feminist, and clearly had difficulty reconciling his chauvinism with his second wife’s gift. Before their marriage, he wrote to her that “You can write better music than any other woman in this country.” Seeger did not comment on how this music stacked up against ordinary male composers’, and ascribed her ability to “the man element in you.” Tick’s interviewees resist accusing Seeger of actively discouraging Crawford from composing during their marriage. She nonetheless subjugated such work to his competitive streak and composer’s block. In 1951, when both were invited to contribute to the prestigious New Music Quarterly, Crawford withdrew all but one of the four scores she had prepared, so as not to overshadow the two that Seeger, after a year of cajoling, allowed into print. She wrote frankly to the journal’s editor: “He with so little and I with so much, I don’t like.” Set against the license to discover “some new chord which will make more variety” she allowed herself for “Lonesome Road,” her later stances suggest a similar self-effacement – not only toward her husband, but the “folk” as well. Crawford’s revivalist turn, while not simply a byproduct of Seeger’s ideological fervor, was overdetermined by doubts about her own right to self-expression as a woman and artist, doubts that neither cultural nor domestic politics did anything to ease.

The balance might have shifted, had Crawford lived longer. After the 1952 quintet, she arranged for performances of her older music, and planned new works. In February 1953, just as the FBI opened an investigation into Charles Seeger’s Communist ties, she was diagnosed with intestinal cancer. Crawford died on November 18, 1953, a few months into what she had briefly hoped would be “46 more years” of composing. According to Pete Seeger, “She didn’t go gently at all.” The true vine can also strangle.

• • •

In her recent essay “Against Musician’s Biographies,” Sara Marcus takes a page from Greil Marcus’ (no relation) emphasis, in Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations on “commonplace songs,” which she defines as “seemingly ‘authorless’ compositions – songs by no one that belong to everyone, that change as they appear and reappear with new interpreters.” “Each new version,” she writes, “carries traces of where the song has been before and perhaps even an anticipation of where it might go next.” For Greil Marcus himself, “the song writes itself” in such cases, and new singers may stumble “into something the song always wanted to say.”[3]

In reversing the focus on star performers on which so much writing about popular music depends, this essay has made common cause with such perspectives. But I also have some doubts. Acknowledging the semblance of anonymity—the fact that we do not know all the facts—easily slips toward denying that composers and songwriters leave a mark on commonplace material, with varied motivations that, like performers’, may include brutally commercial ones. Their decisions bear on performers’ choice of one version of a song over another as a platform for further revision and interpretation. In the case of “(The) Lonesome Road,” Gene Austin and, in a sense, Charles Galloway occupy both roles, but non-performers like Evelyn Cary Williams, Sam Coslow, and Ruth Crawford do not. Distaste for the mass-cultural or learned traditions they represent is not sufficient reason to erase their names and histories, or elide their musical agency.

Acknowledging the semblance of anonymity—the fact that we do not know all the facts—easily slips toward denying that composers and songwriters leave a mark on commonplace material, with varied motivations that, like performers’, may include brutally commercial ones.

This is not to shift the burden of individual genius from performers to songwriters: “(The) Lonesome Road” does not have no authors, but too many. Nor is it to ignore the vagaries of appropriation and exploitation, or uncritically celebrate the commercial (and folkloric) publishing and recording industries. It is, however, to caution against cropping these structures out of the landscape for the sake of a picturesque view. Doing so encourages self-flattery: the sensitive critic, it seems, is always attuned to the uncanny, the ineffable, and the archetypal—but hardly ever to the generic, the synthetic, or the purposefully, even cynically, crafted. I have never been sure how to separate these elements in my own musical experience. When I ask, like Greil Marcus’ auditors, “What was that?”, part of the answer is Sam Coslow’s: “A punchy follow-through.”

There may be songs whose histories are uncorrupted or wholly unrecoverable. “(The) Lonesome Road” is not among them. The road that everybody, including “E.V. Body,” in this story tredges on is crowded with two-way traffic: some stretches are dusty, others are paved with Tin Pan Alley gold or earnest populist intentions, and it is constantly being dug up and laid anew. It runs past farms and fields, churches and prisons, but also, whether or not one appreciates the scenery, through cities, stopping at synagogues, Broadway stages, and conservatories, doubling back on itself at every turn. Traveling on it, you might drift off in the wilderness, far from any road, and wake up in Union Square, or the other way around. When any American, full-blooded or not, tells you there is a song, or kind of song, that has not been changed, or cannot or should not be because accompanying it with another chord or two would be too fancy, or just ridiculous—that is when you should hear a dying song.