America seems in desperate need of heroes. It may be impossible to be a hero in our current era. There is too much news, too much information. Heroes need mystery. They do not need 24-hour news channels, muckraking websites or ironic television talk show hosts. Could Winston Churchill be considered heroic today? Overweight, elitist, cigar smoking, pompous and mannered, but his acts of single-mindedness and unshakeable conviction led him to a heroic stand against one of the great military juggernauts in history.

So where are our great men and women? Where are our heroes? Let us look at the relatively recent tragedy of September 11. There was a feeble attempt to make a hero out of Rudy Guiliani, but the public did not buy it. They knew the real heroes of September 11 remained nameless and faceless. The firefighters, policemen, security guards, who raced back into the burning building. The passengers on the airplane who overcame the terrorists in the face of certain death. But these heroes remain completely unknown, faceless … unsung.

Maybe unsung is the only way a hero can be in these days. But there was a time when grandiose acts, heroic or horrible, filtered so indelibly into the public consciousness that they became the stuff of legends, folktales and folksongs. With every technological gain, there is something lost. Folksongs, real folksongs, songs that are handed down from generation to generation, honed by imperfect memories, polished by the oral tradition, perfected by common consensus, no longer exist. Once you can hear a song on record or on radio, it becomes fixed in your mind. There is no longer the need to try to remember it. The folk songs that were remembered before the beginning of recording history have a spectacular uniqueness. There are no bad folk songs. Why remember a rotten song? Even worse, why sing that bad song to your friend, to your children, to your grandparents?

The folk songs that show up in American oral tradition have a thematic range unparalleled in today’s popular music. Kings and queens, heroes and villains, word play, humor, longing and sexual innuendo are handled delicately and elegantly. All these songs are about something. Sadly, most of the folk songs we remember were pounded into our heads in the preschool years. To me, they became the equivalent of the “Star Spangled Banner” or the Pledge of Allegiance—words that were repeated so often, memorized by rote, that they were drained of all their meaning. Much in the same way that so many of my generation hear Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings and immediately think of cartoon music, because we grew up pasted in front of our television sets watching endless re-runs of cartoons made in the ’30s using a jazz score as the background.

The folk songs that were remembered before the beginning of recording history have a spectacular uniqueness. There are no bad folk songs. Why remember a rotten song?

I was bundled off to elementary school in 1959, in a world that, upon reflection, seems startlingly hallucinogenic, almost a fever dream. Even the smells were different. PS 226, the gigantic edifice erected to instruct the minds that would help us to defeat the communists of the Cold War, was still heated by coal. In the winter, one byproduct of the immense furnace that would heat the school was an egg yolk smell that would mingle with the musty clothing and scent of chalk and erasers. There were elements of my education that mystified me then and mystify me still. Why would we all line up by height to travel from room to room? Why would our attendance be kept in a bizarre system called the Delaney card—tiny slips of paper marked in boxes where your name would be checked off? A world of bathroom passes, hall passes, up staircases, down staircases, desks that so obviously predated the ballpoint pen era that they held copper plated inkwells.

The teachers in my school were the usual cast of earnest hardworking characters who could be found throughout Brooklyn, instructing fidgety kids in the intricacies of long division, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and on rare cases wheeling out a gigantic television so we could stare in awe at some catastrophic occurrence: the death of President Kennedy, the first unmanned launch of a space vehicle.

One teacher stood out. His name was Sid Glassman. Not only was Sid one of the few male teachers in the school, but he was also the guidance counselor, a man who performed a service so mysterious that in my six years in grade school, I never met a single child who visited him in a professional capacity. But everyone knew Mr. Glassman for a different reason. He was the school’s resident folksinger. A couple of times a year, Sid would lug his guitar and a huge pile of mimeographed lyrics into the Assembly. Soon he would be belting out popular folk songs like “Dona, Dona” or “Kumbaya.” And of course, exhorting us to sing along. That is probably where I first heard “John Henry” and the song and the lyrics became just another one of those things you repeat in grade school until they are left empty and dead.

It took a technological revolution to remind me of how great the song really is. In the early 1980s, I bought my first VCR. Absurdly expensive, gleaming in silver chrome, perpetually flashing “12,” as my attempts to program the clock were always frustrated, it nonetheless became a research tool of considerable magnitude. For those of us who love music, it opened the door into the past, giving us a tiny glimpse of those legendary performers who had plied their magic way before I could see them live. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Miles Davis videos would be copied and sent from collector to collector, the visual image soon so degraded that in many cases the performers were just smudgy blurs.

But what a remarkable thing! It was as if a window in time had opened and we could slip through. It did not make a difference that the characters shimmered or the image wavered. In fact, it probably helped. After all, if you slip through time, do you really expect that everything should seem normal? No, things should seem black and white and shimmery and odd and glowing. And that is how I got to see Woody Guthrie. On a traded piece of videotape, shot by a single film camera, in what appears to be a barn. Guthrie stands to the left of the frame with the harmonica and guitar duo Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry circled around him, all singing “John Henry.” This song for them is still completely full of meaning. Woody, his eyes closed, his head thrown back. Sonny Terry, his hands cupped over the harmonica. Brownie McGee leaning in towards Woody to sing the chorus in unison, “Whomp that steel on down.”

This tiny piece of videotape brought me back to the moment when that song still mattered and it made it matter to me. And it conjured John Henry to life and made me reconsider the song’s meaning.

Here is how I picture John Henry: tall, black, arms bulging with muscles. His job is a brutal one. Take a 9-pound hammer and smash a piece of steel boring it deep into rock. Building a tunnel one blow at a time. Ten, twenty, thirty of his fellow steel drivers, all hammering away inside the belly of a mountain. John Henry leads them, slinging a hammer in his hand, sparks flying as the hammer hits the spike that chisels yet another sliver of rock away. As the hammer passes through the air, you can hear it whistle through the wind. As it hits the spike you can hear the metallic clash echoing through the belly of the brutally hot tunnel in the West Virginia morning.

The bossman comes around. He tells John Henry that a man hammering steel takes too long. The railroad company has come up with a new way to build a tunnel. They have got a steam drill and that drill is going to work better and faster and harder than John Henry can. John Henry stares his captain in the eye and tells him he may just be a man and a man ain’t nothing but a man, but there is no machine made, no steam drill, that is going to be able to dig faster and harder and deeper than John Henry can.

Work stops, men gather around John Henry. The captain wants to make an example of him. He is willing to stop work on the tunnel for one day to prove that point. And maybe the captain is not immune to the prevailing race hatreds of the South. Maybe he would like to take down this hero, this big black man, this upstart who the men love because he is strong and deep and soulful and honest. He lets John Henry go head to head, one on one against the steam drill.

… looking for John Henry, finding out who he “really” was, misses the point. The point is that John Henry is a hero, not because he was willing to lay his life down by throwing his body on the hand grenade of the industrial revolution, but because he refuses to let the meaning be drained from his life.

All day long, deep in the bowels of the tunnel, John Henry pours his heart, his anger, his very soul into beating the steam drill. The men gather round, sorry to miss a day’s pay, but glad just the same. Glad because they know that John Henry can show the captain, can show the railroad company, can show everybody that a man can be more than just a man. They know that the bosses, the system, the railroad would love to rob them of their dignity. And to retain dignity against those incredible odds is a remarkable kind of heroism. They are there to watch their John Henry, the man who speaks for all of them, the man who in declaring he is nothing but a man speaks for all men. All day and all night, John Henry faces off against the steam drill and he wins, but the effort is too much for him and in beating that steam drill, he dies.

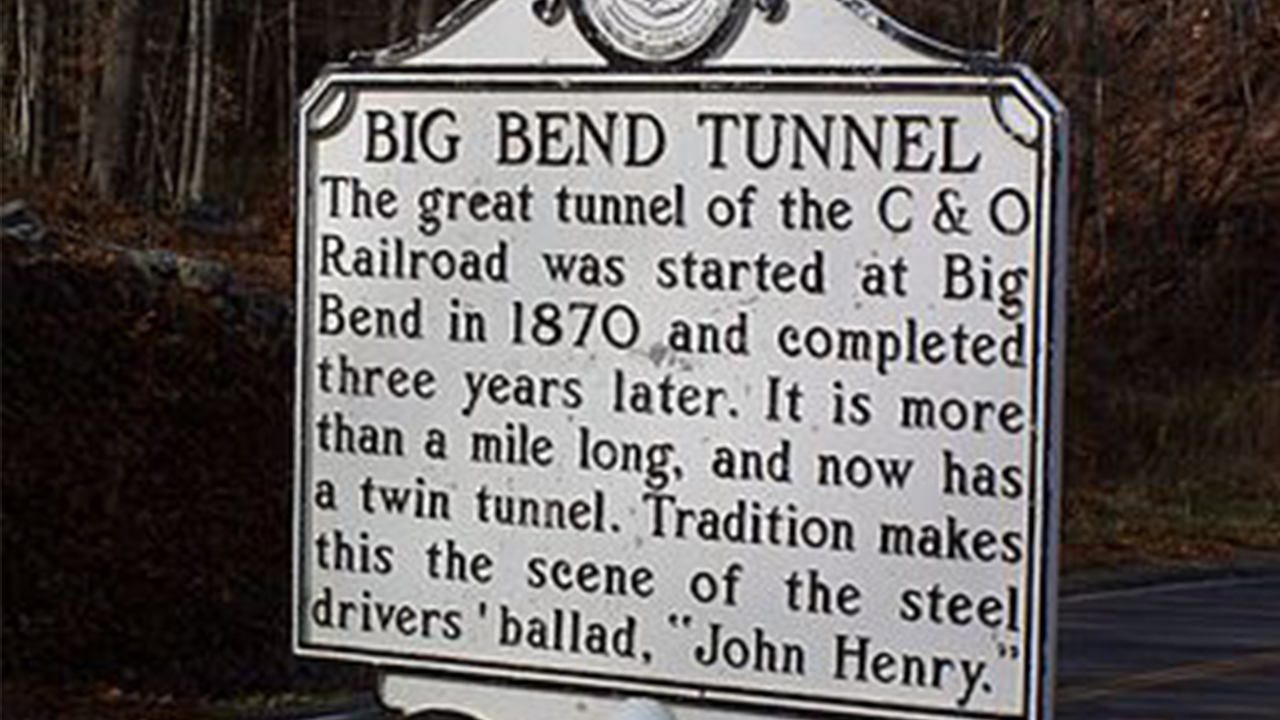

There are thousands of versions of the John Henry ballad. The story and song exist in both black and white American folklore. John Henry has reached such mythic proportions that two recent books were written about him, trying to discover his roots. But looking for John Henry, finding out who he “really” was, misses the point. The point is that John Henry is a hero, not because he was willing to lay his life down by throwing his body on the hand grenade of the industrial revolution, but because he refuses to let the meaning be drained from his life. His life is his work. He is the best at what he does. He would rather die than have what he does be rendered meaningless. And he will fight the bosses and the companies that would rob his life of its meaning, and steal his dignity in the name of progress.

When I was younger I used to think of John Henry in sociological terms; that the ballad was the last cry of the individual being consumed by the industrial revolution. But now I think of the song in much more personal terms. John Henry is fighting an age old battle. All of us are. Something will always come along and render us useless. Old age, redundancy, and time, the biggest bossman of them all, will eventually take the hammer from our hands. Our lives are John Henry’s life. Some smaller but none bigger. When John Henry says he is nothing but a man he acknowledges how small we are, how scared we are, how tiny we are against the mountain, the sky, the job, the work. How the odds are stacked against us. Yet at the same time he refuses to be just a man. His tomorrows do not creep in petty pace, they explode with anger, and skill, with rage and denial. He is our hero. Fighting that battle we all fight. But with pride and skill and defiance and most important of all, dignity.