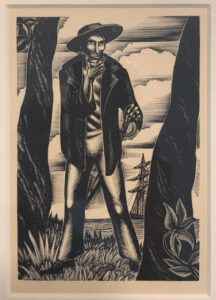

Lynd Ward, from ‘Madman’s Drum,’ 1930.

I have written before about preparing book manuscripts for publication. But not only does each time feel different; assembling my own collections feels different from finishing single-arc books, and editing others’ books feels different yet again.

A few weeks have passed since I finished writing, editing, and organizing the manuscript for my new essay collection, called The Age of Profit, and turned it in to the press for peer review. I wrote many drafts for every piece in the book and in some cases have probably given them a hundred readings. I did much more of that, individually and as a whole, before I turned the collection in, since it is important the pieces say something together that they cannot say individually.

Now I have a few weeks to read the manuscript again, one last time, as a semi-stranger, since time has passed since I last saw it. Soon it will be time to transmit the final, and then it will be out of my hands. As I read I will be judging, well, me in the past, and all my decisions in the prose: Are all his referents clear, his articles necessary? Is he precise without being brittle? What more or less should there be? Does he have music? Is he any good? Best case, I hope to find myself able to read as a reader, not as a writer-editor. But it is hard for the early writer to make something the later writer never wants to alter.

I also will be reading in hope of the manuscript providing some sense of what it was like to perceive and participate in the recent years of calamity. I often tell things slant; the risk is to seem irrelevant, when others were right there in the Oval Office or the Capitol Building and will make their own books. But my favorite writing is often from liminal zones, such as the quiet military graveyard in Hawaii that Didion walks instead of a battlefield in Vietnam.

I am starting to understand too that what I like to read most, in whatever mode or voice employed, contains death. I do not mean only (or even usually) the cessation of respiration, feeding, and growth in a living body. I mean the early perception of the dangers of change, worked out by process to discover its import to the writer.

This is what Bo Burnham means, I think, when he sings the line in his new special that I have used as a title for this post. He lists oddities, banalities, and violence of our time:

The surgeon generals’ pop-up shop, Robert Iger’s face

Discount Etsy agitprop, Bugles’ take on race

Female Colonel Sanders, easy answers, civil war

The whole world at your fingertips, the ocean at your door

The live-action Lion King, the Pepsi Halftime Show

Twenty-thousand years of this, seven more to go

Carpool Karaoke, Steve Aoki, Logan Paul

A gift shop at the gun range, a mass shooting at the mall

He ties the funny feeling to the idea that “we were overdue” (for extinction), “but it’ll be over soon.” Of course, “it” has been going on a long time, and meanwhile there is art as an outlet for that feeling.

What I hope to find, as I re-read my manuscript one (or 20) more times are readerly exclamations: Uh-oh; Oh dear; What was that? Mystery, complications, reversals, and images that stand just inside the tree line and listen hard to something that can never be understood without being destroyed at least a little.