A recent meme made by @aborteddreams

“Welcome to whatever this is,” comedian Bo Burnham says, a few minutes into his new Netflix special. “It’s not gonna be a normal special, because there’s no audience and there’s no crew. It’s just me and my camera, and you and your screen, the way that Our Lord intended.”

Burnham, who is only 30, has been everywhere in recent years and has dozens of credits and many awards as a writer, composer, performer, musician, producer, and director. I had forgotten, for example, until my younger son reminded me, that Burnham was on Parks and Recreation as the obnoxious, cynical Chipp McCapp, and I was surprised to learn that he directed Chris Rock’s Netflix special Tamborine.

Like other Burnham projects, the “whatever” of Inside is a collection of original-song performances, among spoken observations and acting. The difference is that this special was written, performed, shot, and edited by Burnham alone, in what is said to be his house (which I take to be a small studio attached to his house). His songs still take the dark turns his fans love, and his talk is in the tradition of standup that has become often unfunny.

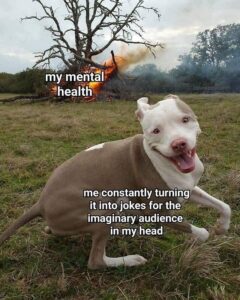

“I hope this special can maybe do for you what it’s done for me these last couple of months,” he says, “which is, uh, to distract me from wanting to put a bullet—into my head—with a gun.” Over the course of what purports to be a year, he portrays himself increasingly doubting his purpose and sinking into depression, anxiety, and derealization.

Inside might be said to be pandemic-cued (most of it seems to have been filmed in 2020) but quarantine is only one aspect of Burnham’s preoccupation with isolation—physical, emotional, social, and existential. (He is apparently in a relationship, and I assume he saw or even lived with his partner, despite the special implying he was always alone.)

As with other hugely-talented Internet acts, such as the Gregory Brothers or Nick Lutsko, Burnham’s music is always skilled, sometimes beautiful, but often in the category of novelty songs. Here these include “Imma FaceTime With My Mom Tonight”; “Sexting,” shot in the style of a Soderbergh film; a synth-pop paean to Jeff Bezos; a workout video in which he erotically performs wokeness and is crucified in light; and the “White Woman Instagram” song, which slams the fetishization of “tiny pumpkins, fuzzy comfy socks,” “incredibly derivative political street art,” self-hugs, and sexualized innocence.

But Burnham is no Weird Al, the Carrot Top of novelty videos by comparison. Burnham is often political and philosophical, and while his material is often parodic, it means to wound like satire. He turns this tendency on comedy itself, too, taking the worst thing you might think to say about his act and making it much worse. In a throwaway bit that lasts a second or two, during a longer questioning of what comedy is allowed to do, he draws an equation on his white board:

Comedy = Tragedy + time

Time = money

Tragedy = 9/11

Comedy = 9/11 + money?

Then he shoots down the meta too: “Self-awareness does not absolve anybody of anything.” Trapped in both his studio and his mind, endlessly turning in on his own thoughts, he is the Charlie Kaufman of standup.

Non-musical segments include a mock “thank-you-for-watching” video, ruined by creepiness as he waves a nasty little hunting knife and grins. In a mock “live-play” vid, he uses a game controller to make himself cry and walk in circles in the studio. As a “social brand-consultant” wanting to know which side of history your brand will be on, he demands, “Who are you, Bagel Bites?”

In one segment he appears as a sort of Fred Rogers. He smiles and says, “Hey, kids, today we’re gonna learn about the world.” A bouncy tune follows, on how “everything works together.”

But when Socko, a white tube-sock on his hand, stops by “to say hello,” it sings, “The simple narrative taught / in every history class / is demonstrably false / and pedagogically classist. / Don’t you know / the world is built with blood / and genocide / and exploitation….”

Burnham turns and smiles as if a child has said something precocious. “What can I do to help?” he asks into the camera.

“Read a book or something, I don’t know,” says Socko. “Just don’t burden me with the responsibility of educating you. It’s incredibly exhausting.” (Socko gets humiliated then deboned for its impertinence.)

The special becomes a musical about dehumanizing influences in our age, especially the alienation that results from the Internet and social media.

“I don’t know about you guys,” Burnham says, lying on the floor, under a blanket, surrounded by cables, power strips, and tools. “But, um, you know, I’ve been thinking recently that, that, you know, that maybe, um, allowing giant digital media corporations to exploit the neurochemical drama of our children for profit? You know, maybe that was, uh, a bad call. By us. Maybe, maybe the flattening of the entire subjective human experience into a…lifeless exchange of value that benefits nobody, except for, um, you know, a handful of bug-eyed salamanders in Silicon Valley…maybe that as a, as a way of life forever? Maybe that’s, um, not good.”

My favorite Burnham character sings “Welcome to the Internet.” Wearing slickster glasses, and with a star field revolving slowly behind him on the wall, he looks and speaks like the Senior VP of Development of hell. He is, by turns, cheerfully frank about the welter of junk to be found online—“anything and everything all of the time”—tender toward our children, and demonic in his high-pitched laughter at how we bought in to what “they” designed the Internet to do. Putting “the world in your hand” turns out to be a curse.

Late in the special, hair and beard long and unkempt, Burnham looks broken. He says he has learned that “the outside world, the non-digital world, is merely a theatrical space in which one stages and records content for the much-more real, much-more vital, digital space. One should only engage with the outside world as one engages with a coal mine: Suit up, gather what is needed, and return to the surface.”

Coming at the end of the special’s emotional arc, it is a startling-enough statement that I check myself to see if it accurately reflects anything of my life after more than a year of pandemic. It does not—much. My elder son, exactly the age of digital user that Burnham’s demonic Internet persona speaks to, stopped watching by the special’s intermission because, he said, it lacked relevance. He also told me his generation’s estrangement from each other was something I would never understand, that the world had changed.

Burnham ends with a song filled with earlier motifs, which seems to earn him release. His exit becomes yet another nightmare with a laugh track, and then just a flickering projection on the inside wall of his isolation chamber.