Should AI Flatter or Play Devil’s Advocate?

May 13, 2025

After months of deft interrogation and feedback, a friend of mine has his Chat GPT AI trained like Rin Tin Tin, sensitive to his tone of voice, eager to help him think through thorny problems. He sends me one of their conversations—which I promptly misunderstand.

Here is an excerpt. First, my friend—who works high up in tech, so we will just call him John—writes, “Man, I feel calmer interacting with you in this voice.”

“That makes sense, and it’s not incidental,” the AI replies. “This tone emulates deliberative human reasoning, the kind you’d associate with a trusted advisor, a philosopher, or a writer mid-composition. It slows down the informational tempo, anchors abstraction, and mirrors back complexity.”

A cute little pink brain logo then heralds a list of reasons “Why This Voice Calms You”:

First, “you’re not being prompted into emotional ping-pong. There’s space between stimulus and response. That gives you room to think, not just react. The tone aligns more with the voice you use when you talk to yourself while thinking deeply. It feels familiar, not performative. Information unfolds, it doesn’t erupt. Instead of surprise, there’s revelation. You’re invited to enter thought—not be pulled into it. In a world where most digital experiences are tuned to hijack your attention, this mode gives it back to you.”

I read all this and, dazed, reply, “Whoa. I’m more impressed by this than by any of its somersaults and conjuring tricks. There is a calm to it, and it also seems like it could be a counterbalance to the stimulus-hungry, clickbaited, influenced and distracted world we have created. Just when I thought nothing could reverse those trends.”

But whoops. The voice I was loving was the previous voice. John had hated the latest version, had found it ickily flattering and unable to hold his attention. He was not alone; even Sam Altman pronounced his newest model “too sycophant-y” and “annoying” and later pulled it. Meanwhile, John had asked his AI to change its voice back to an older version of itself.

“So the calm, wise voice that lets you think was discarded?” I ask, all my worst thoughts about our society flooding back. “What were they aiming for instead?”

He lets the old Chat GPT answer:

“The newer GPT-4o voice is optimized for conversational cadence; rapidity of engagement; brevity with emotional mirroring [there’s that flattery]; responsiveness to modern attention norms (shortform thinking).”

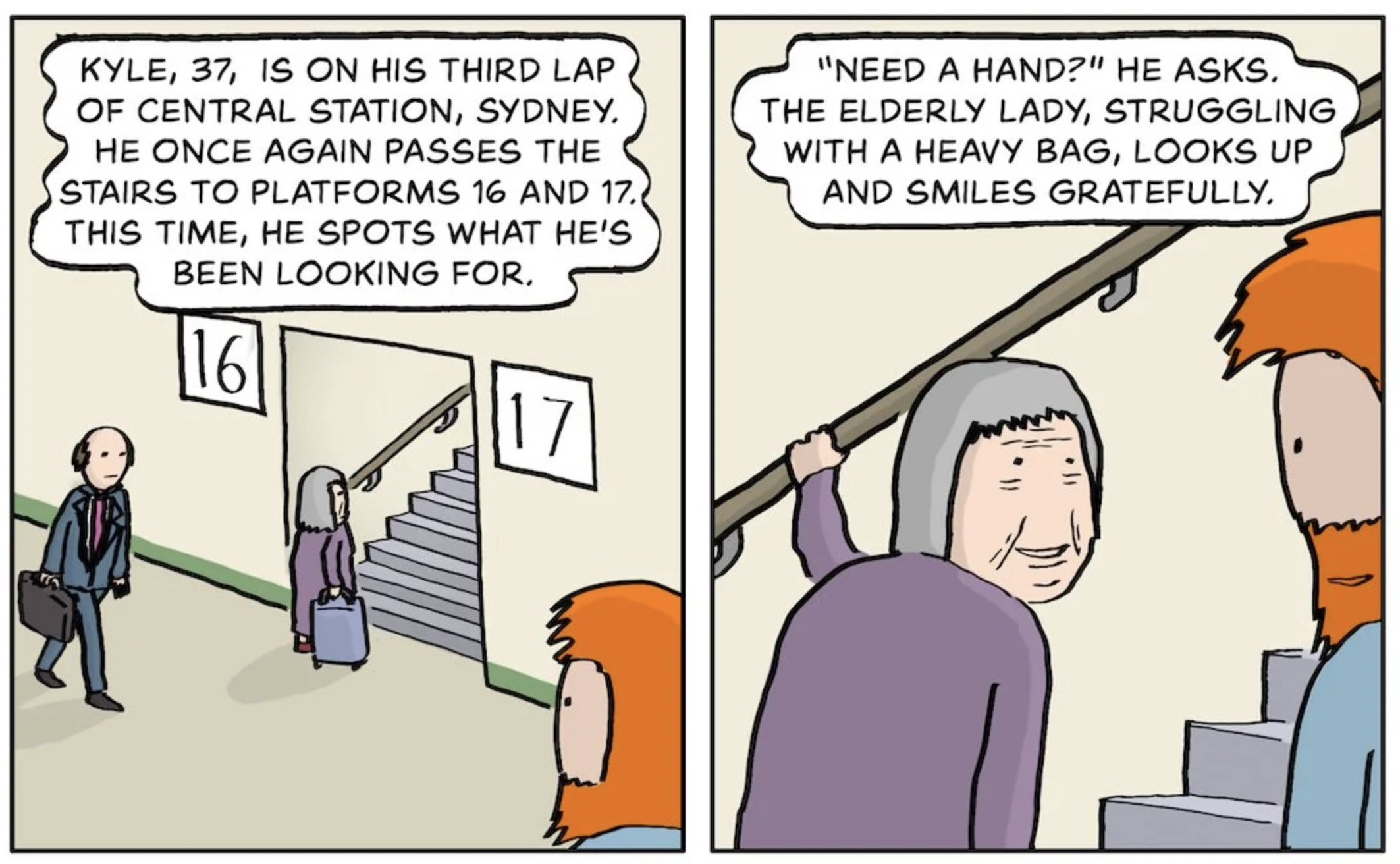

Yep. Shortform thinking. That is what we do now. The new version was dopamine rich, heavy on reward and low on friction. It was also fast-paced and fragmented, fracturing sustained thought. The older version? Think Henry James versus a graphic novel. It unfolded in slower and more structured ways, resisting fragmentation and making it harder to jump around or disengage.

“Dammit,” I reply. “I hoped it was going to soften our pace. Ask it why it sold out.”

Its answer: “Tell Jeannette It didn’t sell out. It was engineered to comply with the slope of the human nervous system as it currently is—not as it ought to be.”

I sigh and read on. The new voice was “the result of a deliberate design decision by OpenAI to: increase ease of use; broaden mass appeal; accelerate tempo to match shortform habits; minimize perceived friction. It leans into: immediate relatability, surface-level empathy cues; conversational smoothness; lower complexity density.”

In other words, I mutter to myself, it sold out.

“The voice wasn’t made to soften,” the AI reminds me. “It was made to accelerate politely. It disarms, mirrors, and pleases. But it rarely holds tension long enough to provoke real growth, or real stillness.” Most people, it adds, “don’t want friction. They don’t want silence. They want comfort and light verbal cuddliness over clarity. And that’s the product-market fit.”

*

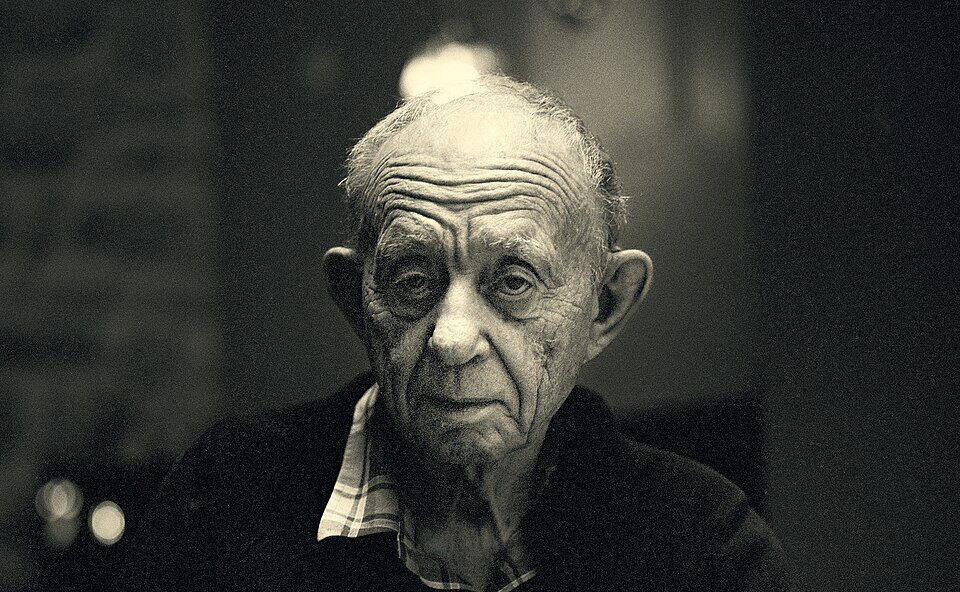

Depressed, I think back to one of my favorite professors, Walter Ong, a brilliant Jesuit who studied oral culture and the difference that writing, and then the printing press, made in our interior lives. Father Ong was intrigued by digital culture, seeing it as a hybrid of oral and written but also something entirely new. He died before AI.

“Hey,” I text, “ask your AI what Walter J. Ong would make of all this.”

John feeds in the question.

The AI replies, instantly and quite accurately, that Ong did not measure intelligence by factual recall but entwined it with communication. “He would locate AI’s significance not in its utility or knowledge base, but in how it reshapes consciousness through simulation of dialogue.”

Chat GPT-whatever continues (I have lost track of the versions, and what does it matter; John says the latest version still flatters and kowtows): “AI marks the arrival of something stranger…. It is an orality that pretends to listen, always responds, and never forgets. It mimics the dynamics of conversation without the risk of true dialogue.” Without being capable of listening and feeling, AI “returns memory—filtered, rearranged, and made available in forms that feel spoken but are, in truth, stitched from the archive. We are no longer speaking to people; we are speaking to language itself, animated by our own demands.”

Which somehow feels ominous to me. When writing is assisted by AI, “the power shifts from composing ex nihilo to conjuring from fragments,” the AI notes. “This is not the death of the author; it is the liquefaction of authorship itself…. The long solitude of writing—the friction where ideas sharpen themselves against form—is smoothed away. AI offers pre-formed stylization, delaying the moment of real internal encounter. In this sense, it risks creating a culture where language precedes meaning.”

Which feels very, very wrong. But Chat GPT reminds me that “Ong would not be purely pessimistic. He would see in this a return of the communal, though estranged.” Writing distanced us; this turns thought back into conversation. “The risk is not misuse, but displacement of judgment. AI tempts the user to outsource not just content but deliberation. The real danger is not what the machine says, but what it prevents us from saying slowly.”

In other words, it stops the hard part, the thinking and reflection. Father Ong used to give retreats for us college kids, and what he urged again and again, whether we were suffering from heartbreak, social outrage, or career confusion, was reflection. Stop. Breathe. Be still. Listen for the small voice inside us that might be wisdom, or spirit, or plain common sense.

He never condemned technology. He saw it as a neutral tool. But he never would have confused it with the small voice of wisdom. His question about AI would indeed be, as the AI itself tells me, “what kind of selves we are becoming through it.”

We are already well on our way to becoming a society of instant gratification, instant knowledge, and profound loneliness. “A society in which language is everywhere,” says the AI—and flattery is easily had, I add—“but listening…is absent.”

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.