Elvis Presley–bloated, over the hill, adolescent entertainer, suddenly drawing people into Las Vegas–had nothing to do with excellence, just myth.

—Marlon Brando

I’ve reason to believe

We all will be received

In Graceland.

—Paul Simon, “Graceland,” 1986

Boredom and fatigue are great historical forces.

—Jacques Barzun

1. You Don’t Know What Love Is

Between 1956 and 1969, Elvis Presley made thirty-one forgettable Hollywood movies. Some were better than others, but it cannot be said that any were truly good. I enjoyed Loving You, King Creole, and Jailhouse Rock on television as a kid, enjoyed Presley as the snarling, snarky southern punk, the New South quasi-confederate with an attitude, the young, arrogant rocker with a chip on his shoulder.

(I never saw Presley’s films in the theater, even though I grew up when they were all first-run feature releases, because the theater in my neighborhood that played them was the Italia, which was strictly meant for the neighborhood Italian kids. We black kids would dare each other about buying a ticket and going in there. No one took the dare; at least no one was willing to risk unpleasantness for a Presley film. As I remember, no one was willing to risk it for a James Bond film either and we all loved Bond back in the day; and this was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with nary a Jim Crow sign, not Philadelphia, Mississippi. The black theater, the Royal, almost never showed Presley movies, because he had few black fans. As Richard Zoglin observed about Presley’s Vegas audiences in the 1970s, “Then, as always, Elvis’s fan base was overwhelmingly white.” (216))

My sisters and I liked Follow That Dream, with the great character actor Arthur O’Connell, and Kid Galahad, with Gig Young and Lola Albright doing the roles that Edward G. Robinson and Bette Davis played in the 1937 version. Even his significant “race” film, Flaming Star, where he played a mixed-blood white/Native American in a western that co-starred the great Mexican actress Dolores Del Rio, and his significant “sectional” film, Love Me Tender, where he played the young brother of a Confederate family, were all right, decent, competent. Good entertainment, as my mother was wont to say about any movie that did not utterly waste her time.

It was the stream of films like Kissin’ Cousins, Clambake, Roustabout, Viva Las Vegas (Ann-Margret’s performance is the only reason to attempt to watch this movie), Girls! Girls! Girls!, Speedway, Girl Happy, Tickle Me, Blue Hawaii, and Fun in Acapulco that I found unwatchable. I have tried repeatedly but been unable to endure any of these to the end. I recently tried to watch The Trouble with Girls, a terribly misnamed film and one that actually had potential with Presley playing the manager of a Chautauqua, but found my attention wandering after a half hour. After forty-five minutes, I muted the sound and left the room, thinking I would come back to it. I never did. For me, Dead Elvis did not happen in the few years before his August 1977 death, the period when he was totally drug-addled, swollen like a decaying beached whale, giving uninspired, sloppy, and under-rehearsed shows to dwindling numbers of fans as the novelty of his return to the stage had worn off. Dead Elvis occurred even earlier than John Lennon and Paul McCartney thought, both convinced that Elvis was never the same after he entered the army in 1958, overpowered and undermined by the establishment that the army represented. Dead Elvis for me was when Hollywood got hold of him and he thought that he would be another Sinatra, another Crosby, a singer turned movie star, the song stylist as actor. (Diana Ross had the same fantasy–that she would be another Streisand, another Liza Minnelli–but it was largely race that worked against her.) Instead, Presley was turned into a zombie, a carcass feeding and being fed upon, acting in terrible movies as if he were waiting for someone either to wake him up or shoot him in the head to end his misery. Presley suffered from the two major afflictions of twentieth-century western life. The first, Jacques Barzun once suggested no one took seriously but destroyed more people than physical ailments, was the truly invisible pandemic: boredom. The second, which untalented people use as a spur for political activism but which torments and saps the talented, is the quest for authenticity. These were Presley’s twin antagonists. They ate him alive or, to borrow from Ian Fleming, Presley wound up passively disagreeing with the somethings that ate him.

Why, with so much going for him, did Presley fail so monumentally as an actor and eventually even as a stage performer, his claim to fame to begin with? Why did he not turn to television when his film career went sideways? … Part of the answer is that the extent of his fame trapped him into not retrenching in any way as that would have been a public acknowledgment that perhaps he did not deserve his fame in the first place.

Presley’s end was not from lack of talent. There is nothing to indicate that either Sinatra or Crosby had more talent as either actors or singers than Presley. In fact, Presley was better looking than either man, was just as good a singer (if not, in some respects, better), and was associated with a musical form that was more subversively sexual and culturally revolutionary, rock ’n’ roll. So, that is not why his career derailed so spectacularly. When I saw him in Loving You, the first Presley movie I ever watched as a child, he seemed electric, far more compelling a presence to me than Sinatra, Crosby, or Dean Martin.

Compare Presley’s Hollywood career to World War II hero Audie Murphy, born in Texas, winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, who appeared in nearly forty-five films from 1948 to 1969. Murphy was not a better actor than Presley, although he made the most of his talents. He was as troubled in his personal life as Presley, if not more so, as he had experienced the trauma of combat. And he appeared in a large number of westerns, a genre no longer popular among filmgoers by the 1960s. Yet Murphy’s work is far more watchable and valuable than Presley’s. Indeed, in some films, like The Quiet American and The Red Badge of Courage, Murphy not only had better source material but gave performances that were far better than anything Presley ever did. Even Pat Boone, Presley’s friendly singing rival, the “clean-cut boy,” could hang his hat on one enduring classic film, the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, based on the Jules Verne novel that co-starred James Mason and Arlene Dahl. Presley did not even have that. In fact, Boone’s 1962 starring turn in the film version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s State Fair (which also featured Ann-Margret), purely as a musical, is stronger than most of Presley’s musical films. Why, with so much going for him, did Presley fail so monumentally as an actor and eventually even as a stage performer, his claim to fame to begin with? Why did he not turn to television when his film career went sideways? Many other Hollywood actors from the so-called Golden Age did, including Barbara Stanwyck, Loretta Young, Doris Day, Dick Powell, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Bing Crosby, Peter Lawford, Michael Rennie, Bob Hope, Rory Calhoun, Yvonne De Carlo, Ray Milland, and Dorothy Malone, to name a few. Why did he not choose to go to the stage as an actor when the films ran dry? Part of the answer is that the extent of his fame trapped him into not retrenching in any way, as that would have been a public acknowledgment that perhaps he did not deserve his fame in the first place.

Presley’s fans loved him, of course. But perhaps they really did not quite know what it was they loved. He was a mystery, maybe as much as that train that he sang about, and maybe because of the particular type of white southerner he was. Certain white southerners are more opaque than we give them credit for, the lost confederates in the attic of our minds. Even blues singer John Lee Hooker loved the confederate when he sang, “I’m bad, like Jesse James.”

As Zoglin points out, Frank Sinatra, joking to friends about why he slightly preferred the Beatles over Elvis, said, “At least they’re white.” (151) Marlon Brando put it another way: “It seems to me hilarious that our government put the face of Elvis Presley on a postage stamp after he died from an overdose of drugs. His fans don’t mention that because they don’t want to give up their myths. They ignore the fact that he was a drug addict and claim he invented rock ’n’ roll when in fact he took it from black culture.” For Sinatra, one type of American hipster, Presley was somehow inauthentic or untrue because he was too blatantly miscegenated. For Brando, another type of American hipster, Presley was a fraud because he was a minstrel, an impostor doing the white man shuffle. (Did not Brando wind up bloated, over the hill, and living on the memory of his myth? At least Presley did not, in such a hollow and vain way, denigrate his profession as Brando did.) Sometimes, when I think about Presley, Muhammad Ali comes to mind. They had this much in common: both were southerners, albeit Ali was black which makes a substantial difference; both achieved new heights in their careers in the 1970s but deteriorated badly during the same period; both learned something about performance and self-presentation from Liberace. Both learned from Liberace that exaggeration and myth are the heart and soul of art and the selling of it.

- Nice Work If You Can Get It

I walk a lonely street.

—Line from a suicide note that inspired “Heartbreak Hotel” (205-206)

He was a complete outsider. He knew nothing about show business.

—Corinne Entratter, wife of the manager of the Sands, assessing Elvis’s performances in Vegas (222)

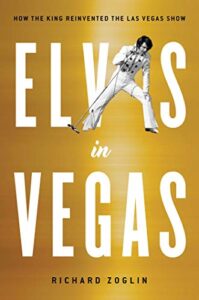

When Elvis played the International Hotel on the Las Vegas strip on July 31, 1969, the beginning of a four-week engagement, it marked officially the end of his movie career. But as Zoglin points out in Elvis in Vegas, it was not the first time Elvis played Vegas. He first played Sin City on April 23, 1956, performing at the New Frontier Hotel and Casino: “The idea was his manager Colonel Tom Parker’s, and not a very good one. Elvis’s frenetic rock ’n’ roll performances, which were causing such a sensation in the rest of the country, were hardly geared for a crowd of middle-aged Vegas showgoers.” (3) Thirteen years later, the crowd was still largely middle-aged, but this time they were people who had grown up on Elvis’s music and on rock music in general. In 1969, the reception was different, as Zoglin notes, from the first bars of the opening number: “As he sang ‘Blue Suede Shoes,’ the crowd erupted. It was the old Elvis, rocking as hard as ever on one of his classic hits, a song they hadn’t heard him sing in over a decade.” (196)

Presley was a lone and, in some ways, lonely figure. This loneliness, this lonesomeness, is rooted for me in the aura of Elvis as a white southerner: he represented, ironically in light of his energy as a new force in popular music, a form of exhaustion.

Elvis in Vegas is about this moment of resurrection for Elvis, the triumphant return to Vegas in 1969, the course correction from the abominable film career. Zoglin makes two important points about Elvis’s return as a live performer: first, Elvis did not return as a nostalgic or “oldies” act. He did all his old ’50s rockers but “faster than in the old days—with a certain distance, almost self-parody, as if he were trying to get through them as quickly as possible.” (198) He concentrated on his new material: Mac Davis’s “in the Ghetto,” which became a big hit for him, “Kentucky Rain,” and “Suspicious Minds,” another big hit for him. With the jumpsuits, the large orchestra, the two groups of back-up singers (one made up of black women and the other of white men), Elvis, at least for a time, had a second act. Second, Presley changed the nature of the Vegas show from the Great American Songbook and Tin Pan Alley to Nashville, rhythm and blues, and country. And Elvis invented Elvis for the stage: “For his big comeback show in Las Vegas, Elvis had no director, no producer with any hands-on involvement, not even a music-industry guru or Vegas veteran whom he could rely on for advice in shaping and staging the show,” Zoglin writes. “Elvis was as ready as he could ever be: well-rehearsed, backed by first-rate musicians, and heralded by the biggest publicity campaign in Vegas history. Yet his show still has something of a homemade, seat-of-the-pants quality.” (179, 193) What Elvis wanted to show was that one could be every inch the song stylist in those genres as Sinatra or Crosby could for the Pop Songbook and the Broadway musical, that a true song stylist was sui generis, something that could be designed but not formularized. In this respect, Presley was an auteur, so singularly, naively, yet magnificently constructed, that his Vegas self is indelible as an icon. This was every bit as liberating and transformative for American popular culture and the American performer as what the Beatles did, who had nowhere near the charismatic presence on stage that Presley had. The common observation is that the Beatles eclipsed Elvis by the mid-1960s but as Elvis said wistfully, “There’s four of them. But there’s only one of me.” (152) And what Presley had achieved in popular music before the coming of the Beatles was unprecedented, and remains startling even today as few have matched or surpassed his sales figures or his influence. Presley was a lone and, in some ways, lonely figure. This loneliness, this lonesomeness, is rooted for me in the aura of Elvis as a white southerner: he represented, ironically in light of his energy as a new force in popular music, a form of exhaustion. Presley always seemed to be running out of inspiration and interest: with his movies, with his Vegas show eventually, and, if the relentless drug addiction meant anything, with his own consciousness. He became a twentieth-century version of what William R. Taylor stereotyped in his classic 1961 study, Cavalier and Yankee, as “the doomed white male southerner.”

Of course, one might wonder why the book is over 250 pages if it largely concerns Elvis in Vegas in 1969 and 1970. That would seem the subject of an essay, not a book. Zoglin spends most of the book describing the history of entertainment in Las Vegas since World War II, the rise of casino culture, the influence of organized crime, the formation of Sinatra’s Rat Pack, the careers of Wayne Newton, Liberace, Bobby Darin, Keely Smith and Louis Prima, and various other performers who were seriously impacted by Las Vegas. (There is no mention of how air conditioning, the interstate highway system, and the rise of commercial airlines made Las Vegas possible.) For this reader, this account of Vegas was certainly not new, as I have read a number of biographies of various performers who worked in Vegas as well as a few histories of the city itself. But for those with no such familiarity, this account, though repetitive, may be useful context. It could easily have been shorter, but then Simon & Schuster would have been stuck with a very skinny book. Nonetheless, for those interested in Elvis, Las Vegas, and its place in American popular culture, or changing trends in popular music, Elvis in Vegas is worth reading.