When I was six years old my sister, who was nearly three years older, gave me my first lesson in Major League Baseball by teaching the line-up of the Milwaukee Braves. She liked the Braves I suppose because at the time, the glory years of the late 1950s, they were a pennant-winning team. She may have liked them as well because they had a star Black player, Hank Aaron. The Philadelphia Phillies did not and would not until the coming of Dick (Richie) Allen in 1964, the year of the Philadelphia Columbia Avenue race riot and the Great Collapse in the final twelve games of the season. (Allen died on December 7, 2020, and I will have much more to say about him in a future issue of The Common Reader.) I guess that is why my sister favored the Braves for the brief instance that she had an interest in professional baseball—a winning team with a star Negro player, as it would have been expressed at the time—but I really am not sure. I know she also liked the word “Milwaukee.” It sounded funny, like Schuylkill.

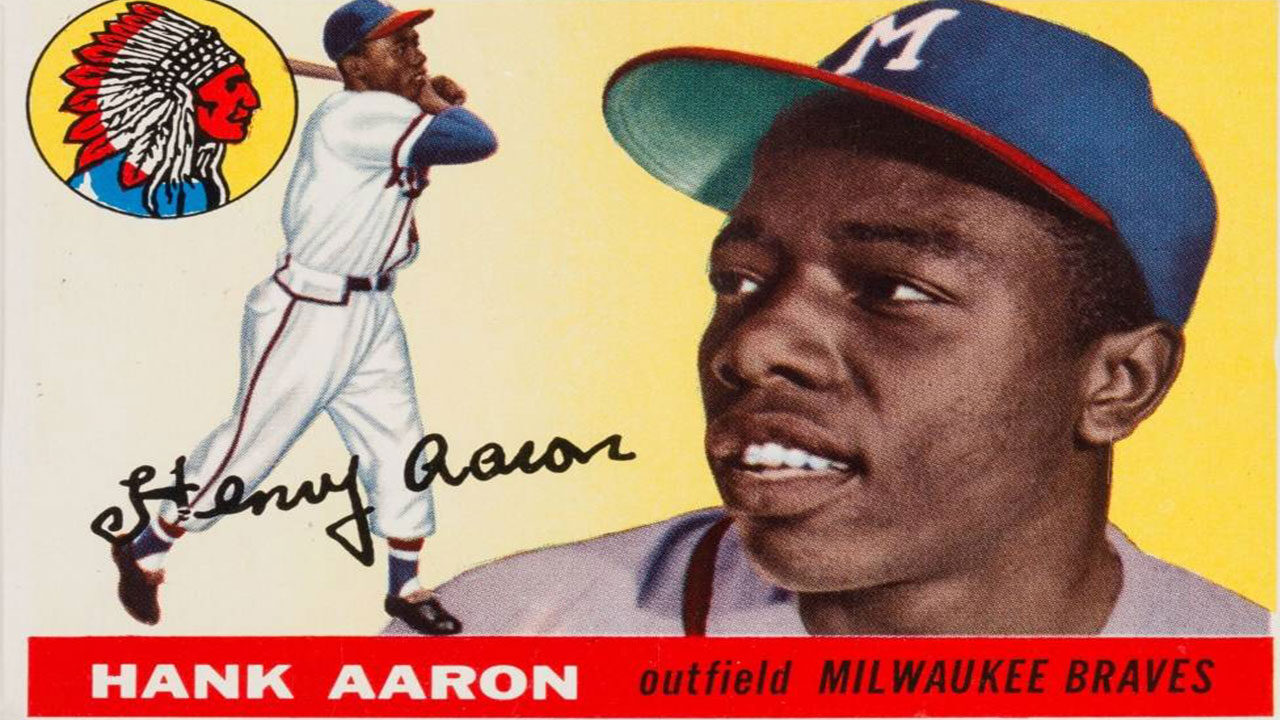

When I saw Aaron on a baseball card my sister had, I liked him but I liked his uniform more. I just loved those old Milwaukee Braves uniforms with the tomahawk and the Indian icon, the thin red stripe circling the collar. The name itself, Braves, made me think of young, tough warriors. I did not know what a “Phillie” was and whatever it was seemed lame. What I remembered most about what my sister taught me was that the Braves had two great hitters, outfielder Aaron and third baseman Eddie Mathews, who would eventually manage Aaron in the later part of Aaron’s career and was protective of Aaron in the outfielder’s early days. One Black and one White. This struck me as a wonderful thing and baseball became for me this island of civility where Blacks and Whites played together, worked together, lived together (for the season, at least). Baseball was a world apart from the world I actually lived in. Baseball was the world where I wanted to live. This made baseball special for me and my Negro boyhood friends and we identified with both the Negro and White players. After all, we played baseball with the White boys in the neighborhood (more often against them but not always). Baseball, for us, was America, or what we hoped it was.

When I saw Aaron on a baseball card my sister had, I liked him but I liked his uniform more. I just loved those old Milwaukee Braves uniforms with the tomahawk and the Indian icon, the thin red stripe circling the collar.

(As I learned as a teenager, Mathews really could not protect Aaron in some respects, from the “good old boy,” “unreconstructed,” dumb carouser-types on other teams who were, shall we say, a bit ambivalent about the integration of baseball, the type of White players on the Braves that Mathews referred to as his “Asshole Buddies.”¹As Aaron noted in the early 1960s, “Pitchers have knocked me down a lot, and sometimes, it goes through my head that they’re throwing at me because I am a Negro. What makes me think so is that Eddie Mathews is just as much a hitter as I am, and I’ve batted right behind him for nine years now and have never seen him knocked down.”² Mathews may have never been knocked down because he was White, but not quite for the reason of being White per se. He was probably never knocked down because everyone in the league knew that Mathews would knock the offending pitcher on his ass if he threw at him. Mathews had a reputation for not “taking shit” on the field and he was tough enough to back it up. He was what is called in hockey an “enforcer.” Aaron could not do that, even if he were inclined temperamentally or emotionally to do so and tough enough. That kind of behavior, intimidation, from a Black player would have been far less tolerated. A White player’s privilege, you might say. A Negro player had to stand up to intimidation without seeming a source of it. I was just an anonymous colored boy in those days and it took me a while to learn these things.)

I went to Connie Mack Stadium, Shibe Park to the older generation, fairly often as a kid, not to see the Phillies but to see the opposing team, especially the Dodgers (to see Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale pitch), the Pirates (to see outfielder Roberto Clemente), the Giants (to see Willie Mays and the majestic Juan Marichal), and the Braves (to see Aaron but also to see pitcher Warren Spahn and Eddie Mathews). I saw Aaron hit a home run at a game I attended. I will never forget how hard he hit the ball, and how effortless and graceful his swing. Oh, those magical wrists of his! I imitated that swing for a while when I played youth baseball. It made my wrists and forearms ache. That did not dissuade me. I finally stopped when one of the coaches said I would hit better if I stopped doing a poor imitation of Aaron. My hands were big, so he would yell at me to just use my hands to hit, not my wrists. “Don’t lead with your wrists,” he would shout, “Just let your wrists follow your hands.” He was right. When I stopped imitating Aaron, I did hit better. I guess Aaron’s way of hitting worked for Aaron and probably nobody else, certainly not for star-struck kids of small talent like me. That is the way it is with great hitters, sui generis.

As I remember, Mays was much more publicized when I was growing up than Aaron because he was a more flamboyant player. Aaron never seemed as if he were playing very hard; Mays seemed a whirling dervish. If Mays had been an actor, he would have been the worst scene-stealer in history. For a time, everyone thought that if any player from the post-Jackie Robinson era was going to break the career home run record, it would be Mays. Even Frank Robinson was talked about more than Aaron, especially when he won the MVP in the National League in 1961, and in the American League in 1966. Aaron won the MVP only once. To underscore the magnitude of Robinson’s second MVP, he also won the Triple Crown that year. Aaron never won a Triple Crown. During a game, Robinson, a very fiery, hard-charging ballplayer, was once knocked unconscious by Aaron’s teammate Mathews, the hard-drinking, two-fisted “enforcer,” for being a bit too fiery while running the basepaths to break up a double-play. (Robinson would claim that he “won” the fight because his team won the game. He continued to play despite the beating.) Aaron was never knocked out by any opponent because he was a cooler player, a cool player. And everybody knows that while some like it hot, most like it cool. So, the “hot” Robinson was the talk of the town, until Aaron the cool started getting close to Ruth’s home run record. But Mays petered out, his body ran down quicker, his road to the record was harder. Aaron, the less emphatic but no less determined ballplayer, outlasted Mays.

I will never forget how hard he hit the ball, and how effortless and graceful his swing. Oh, those magical wrists of his! I imitated that swing for a while when I played youth baseball. It made my wrists and forearms ache. That did not dissuade me.

To break the record was a sign of longevity and the persistent excellence of the gifted who knew how to work the gift with care; it was also luck not to have been injured to such an extent as to have missed a great deal of playing time. Aaron had endurance, good genes, could stay in the line-up and produce which, of course, kept him in the line-up. A vicious cycle that circles around you, as Yogi Berra might have said. It was even good for Aaron not to have played for a team that was consistently competing in the World Series. After 1957 and 1958, the Braves never played in the World Series again while Aaron played for them. They were bounced in three straight games in the 1969 National League playoffs by the Amazin’ Mets. The Braves, in the 1960s, were an underachieving team. They were not hungry enough. Strong hitters, weak pitching, indifferent managing. Aaron was under the radar a bit and I think this may have helped him, a less intense spotlight. Also, when the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966 in what was a messy divorce from Milwaukee, Aaron was aided by the fact that Fulton County Stadium was an easier place to hit home runs. Mays was penalized by the fact that the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1957 and Candlestick Park was a much harder place to hit home runs, a cold, wind tunnel of a stadium. Once I heard a story that Mays clobbered a ball at Candlestick that was a sure home run but it got caught up in the crosswinds of the stadium and wound up being caught by the second baseman in short center field. Athletic contests are won by skill, will, and luck. And athletic records are made the same way. To break the record, Aaron had to pace his decline. How long can you outrun losing what you had? That is what it comes down to for an athlete to bring a longevity record like career home runs.

When I was older, a young teen, and much more knowledgeable about professional baseball, the men in the barbershop where I got my hair cut would sometimes talk about the current Negro stars: at the time, Robinson, Mays, Tommy Davis, Jimmy Wynn, Maury Wills, Mudcat Grant, Wes Covington, Willie McCovey, Billy Williams, and of course Aaron. Everyone was assessed against Jackie Robinson or against some guys from the Negro Leagues I never heard of like Luke Easter, Sam Jethroe, Buck Leonard, Oscar Charleston, Martin Dihigo, and some other “blasts from the past” as far as I was concerned. “Who the heck are those guys?” was what all us youngbloods thought. “There ain’t no Negro Leagues anymore, why do they keep bringing that junk up for?” One barber once said, “Aaron’s good for a lazy Alabama boy. He can get away with that ’cause he playin’ with them White boys. They’d be on his ass if he was still in the Negro Leagues.” I never forgot that. I did not understand it at the time. How could these guys heckle a great player like Aaron, then a bunch of colored barbers who did not know anything, who did not even know how to cut or process hair right, as I saw it? Later, I realized it was a way of acknowledging Aaron’s greatness, a kind of hazing that a lot of Negro sports fans of that generation did, holding up the Negro Leagues as a kind of excellence because we had so few standards of excellence that we could call our own. Playing in the Negro Leagues was like going on the bandstand for a jam session with Bird, Diz, Bud Powell, and Max Roach. You had to know the changes or be told to sit down. There was no room for what Diz called “no-talent guys.” To be excellent, to be gifted, was to be a hero. And Negroes then rode their heroes like overworked thoroughbreds, from ready to ruin. When Aaron got close to Ruth’s record, several years later when I was in college, the same barber said, “I’m pulling for Aaron. I hope he busts that record so bad that ain’t nobody gonna be near it again. I hope he breaks that record and breaks all the White people’s hearts.”

Playing in the Negro Leagues was like going on the bandstand for a jam session with Bird, Diz, Bud Powell, and Max Roach. You had to know the changes or be told to sit down.

Aaron was probably the second most important Black athlete of the 1960s. Only Ali was more significant, and more flamboyant. In Jackie Robinson’s book of interviews about the integration of Major League Baseball, Baseball Has Done It (1964), Aaron mentions that he had read James Baldwin. “I’ve read some of James Baldwin’s books. He is a very good author with very good ideas. I haven’t read The Fire Next Time, but a friend of mine talked to me about it. Baldwin says we’ve waited long enough.”³ As a kid, I was impressed with that. It was news to me that Negro athletes thought about such things, they being rich and famous and all that and not really like the rest of us. I was a colored boy and learning.

The mostly White sportswriting establishment, “woke” to the max, began a great deal of pious braying after Aaron died that he was the true home run king and not the cheating, steroid-fueled Barry Bonds. I have mentioned elsewhere how much this sort of thing sounds like Aaron is the good Negro and Bonds is the bad Negro. Whites have always loved doing this, deciding which Negroes they approved of as the Negroes who were a credit “to the game,” in Aaron’s case, which is like being “a credit to your race.” Even in this so-called “woke” age, as some think of it, Whites continue to define Negroes as they did 150 years ago. The more things change, as they say, the more they remain the same. This might lead some to think that racism and anti-racism in some respects, to borrow the language of avant-garde bandleader Sun Ra, “are really the same upon different degree.” But forgive me if I seem to be provocative for provocation’s sake.

Aaron was an incredible player. He lived a long life. And he got his due, his accolades, his recognition, while he was alive. That is good. I wonder if a great athlete who breaks a record thinks, in the words of Cole Porter, “Is it for all time or simply a lark?” What does it mean to be remembered? So many players from the Negro Leagues never did get their due. When I was a kid only those older men who had gone to Negro League games as boys and young men remembered. Those barbers from my boyhood knew more than some ignorant kid like me and that is why they said what they said. They knew more about what it meant to be colored than I ever would.