…for the American Negro is possibly the only man of color who can speak of the West with real authority, whose experience, painful as it is, also proves the vitality of the so transgressed Western ideals.

—James Baldwin, “Princes and Powers,”¹ his account of the 1956 Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists which took place at the Sorbonne

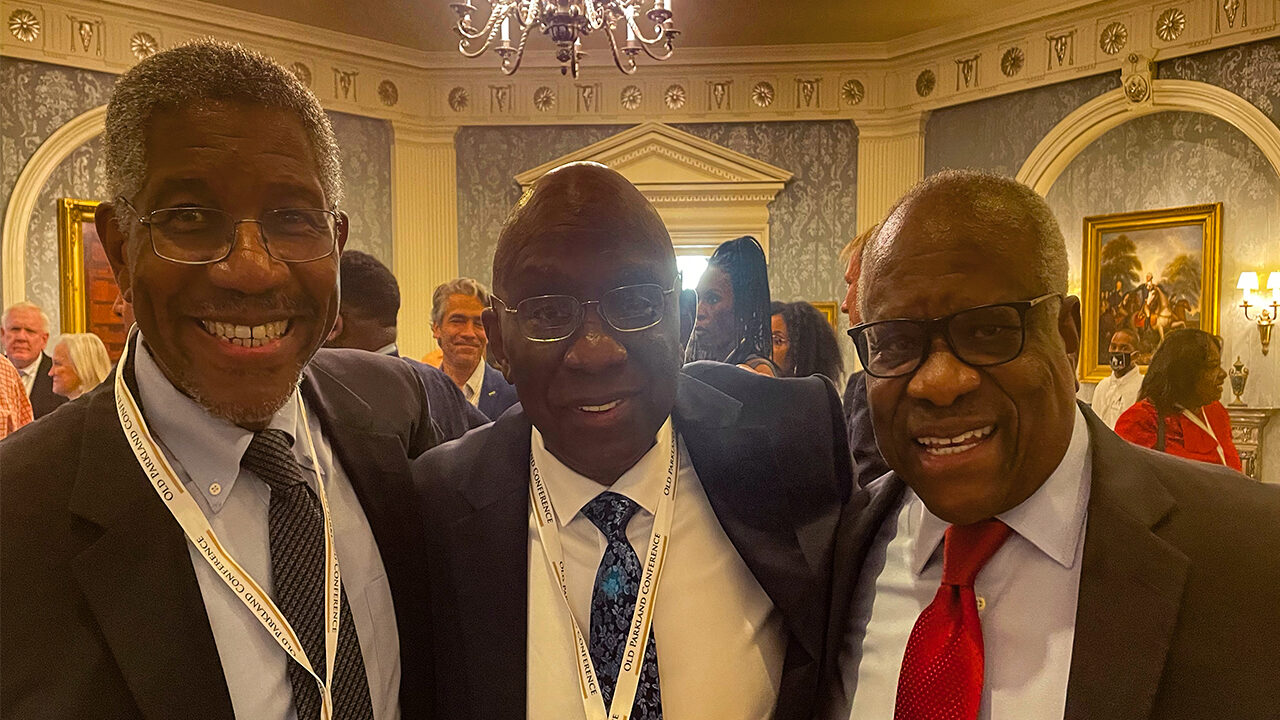

Thomas Sowell, the sage as the prince

The recently held (May 12-14) Old Parkland Conference, sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute, the Hoover Institution, and the Manhattan Institute, three of America’s leading conservative think tanks, was described by many of the speakers as something like the Fairmount Conference version 2.0. What is now commonly referred to as the Fairmount Conference, which took place on December 12 and 13, 1980 in San Francisco at the Fairmount Hotel, was actually entitled “The Black Alternatives Conference.” The press dubbed it the Fairmount Conference. “The Black Alternatives Conference” was largely conceived and organized by economist Thomas Sowell,² who, in 1980, in the immediate aftermath of Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory, found his name being bandied about for Secretary of Labor, a job he did not want, although he was asked by a Reagan White House staffer if he might be interested in it.³ He was also asked if he would be interested in being Secretary of Education, which he also declined. “By that time,” Sowell writes, “I had resolved in my own mind that I did not have the political skills or temperament to accomplish anything that would justify the aggravation that going to Washington would involve.”⁴

In 1980, Sowell was emerging as the most prominent Black conservative intellectual in the country. In many respects, he remains so. Within months following the Fairmount Conference, Ethnic America was published, a widely reviewed, highly popular book that would make him, arguably, the most famous and talked-about Black scholar in the United States. (I recall a number of Blacks at my church reading it at the time, impressed, but unsure if they should be or ought to be because it challenged some assumptions they considered to be truths.)

Sowell wanted to write books, which he has done at a staggering rate over the course of his career. Working in government would have made that impossible and would have likely blunted his impact, not enhanced it. After a brief and unhappy career as a professor, he became a fellow at the Hoover Institution in 1980 and remained there his entire career.

Thomas Sowell, like every great scholar, is something of a zealot and a knight. The showing of the video made it seem as if the Sowell of 1980 was giving this 2022 conference a sort of benediction while passing the torch.

Sowell was not present at the Old Parkland Conference, age and poor health—he is in his early 90s—prevented it. But the conference was, in many ways, a tribute to him: many of the panels were titled after his books, his name was evoked repeatedly, and the facility where the conference was held, Old Parkland, has a statue of Sowell, a singular honor, among the many artistic representations, mostly paintings, it has of economists, writers, entrepreneurs, and inventors. The Prince of Black Conservatism—the Maverick as biographer Jason Riley called him—was enshrined in a kind of intellectual and artistic hall of fame.

At the outset, on the first evening of the Old Parkland Conference, right before dinner, participants were shown a short video of Sowell speaking at the Fairmount Conference with the usual mixture of intellectual swagger, sharp wit, and utter confidence that characterized him as a public speaker. In the clip he said, among other things, that the only people who were escaping poverty through government programs were the bureaucrats who ran them. That mordant line, as expected, greatly amused the gathering, garnering applause. Whether or not one agrees with his ideas, there was never a question that he has a formidable mind and that he has entered the lists prepared for battle. (I thought at that moment of my late friend, the acerbic jazz and social critic Stanley Crouch and how he always signed off with “Victory is Assured.”) I suppose Sowell, like every great scholar, is something of a zealot and a knight. The showing of the video made it seem as if the Sowell of 1980 was giving this 2022 conference a sort of benediction while passing the torch.

Sowell wanted to do a follow-up to the Fairmount Conference which he thought was “a bigger success than we expected,”⁵ but became too busy to do so, as well as a bit discouraged that he had to do a lion’s share of the work.⁶ Forty-two years later seems an extravagantly long time for a follow-up and I found it curious that Black conservatives do not hold a conference like this every few years, to maintain the morale, the message, and the mission. One common criticism that liberal and leftist Black scholars make about Black conservatives (or Black Republicans in this case) is that they are disorganized.⁷ Perhaps they are. Perhaps intense organization is not desired among this gathering. As Sowell said at the Fairmount Conference, “We are here to explore alternatives, not to create a new orthodoxy with its own messiahs and its own excommunications of those who dare to think for themselves.”⁸ Too much organization strives for dogma.

• • •

The inequality blues

At the start, Wall Street Journal columnist, Manhattan Institute senior fellow, and conference co-organizer Jason Riley said that the Old Parkland conference was about racial inequality in America. This struck me as the conundrum that undermines Black conservatives or makes them suspect. Conservatism as a general political principle does not find inequality abhorrent on its face. In fact, conservatives defend inequality as natural, a norm, inevitable, an arc of distribution in human life according to talent, willingness to work hard, state of bodily and mental health, family advantages, ambition, the strength and integrity of a society’s institutions, and a host of other variables. How people are arranged across the spectrum of society is not, in their view, a prima facie case of unfairness. For them, enforced, government-regulated equality—“universal fairness”—would produce something akin to the oppressive society described in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1961 satire “Harrison Bergeron.” They endorse mechanisms to create opportunity but are far less sanguine about mechanisms to create equality.

Black conservatives are convinced that racial disparities, on their face, are not proof of racism and that it has been dishonest and irresponsible, cynically opportunistic, of Black leftists or Black anti-racists to claim so.

On the other hand, how can these Black conservatives not claim so? The fact is that many people—liberals and leftists particularly—react with especial displeasure, utter contempt, when Black conservatives are not vehemently opposed or absolutely alarmed about inequality generally or racial disparities in particular. How can these conservative intellectuals and activists, as oppressed and brutalized as all Black people have been by elaborate structures and systems of inequality, wind up defending inequality per se as a social necessity or something that is socially unavoidable? Did not Blacks endure state-sanctioned and culturally supported inequality during slavery and the Jim Crow Era?

Black leftists hate bourgeois civilization as parochial, corrupt, unjust, oppressive, and deceitful, while Black rightists see it as offering useful, workable, and largely laudable norms and workable prescriptions to manage one’s life to fit these norms. Both sides are equally products of it. The Black rightists can claim that they are not hypocrites nor ingrates. The Black leftists can claim they are on the right side of history in their opposition to hierarchy and the superstitions of power.

The conservatives’ belief in merit, personal responsibility, religious faith, individual effort, delayed gratification, thrift, conventional morality—all of which the left considers the dated shibboleths and hobgoblins of the vacuous bourgeois mind—would of course produce inequality as some people would simply manage their lives better than others. The left would sneeringly and sarcastically call this the conservatives’ “virtuous inequality” or “the equality of the deserving.” For the left, social, political, and financial advantages matter, subverting any notion of “virtuous inequality.”

But I suppose the bitter difference here between the two sides is the point. Probably neoconservative Irving Kristol was right when he wrote that equality “is a surrogate for all sorts of other issues… these involve nothing less than our conception of what constitutes a just and legitimate society.”⁹ These two sides have different views of what constitutes a just society. Black leftists hate bourgeois civilization as parochial, corrupt, unjust, oppressive, and deceitful, while Black rightists see it as offering useful, workable, and largely laudable norms and workable prescriptions to manage one’s life to fit these norms. Both sides are equally products of it. The Black rightists can claim that they are not hypocrites nor ingrates. The Black leftists can claim they are on the right side of history in their opposition to hierarchy and the superstitions of power. Much of this difference can be ascribed to what each side values in the Black experience: the leftists value protest, White de-legitimation, and resistance; the rightists value adjustment, mainstream success, and striving. As one of the conference organizers, economist Glenn Loury put it, “People must have hope to make their lives better through their own efforts.” The left’s response to this is “Some more of the politics of respectability crap! Been there! Done that! Is degrading! Does not work!” The right’s rebuttal is “Is uplifting! Is validating! Is the only thing in human history that has worked!” One side wishes to cleanse; the other to give consent. The Enfants Terribles versus the Faithful Children.

If this had been a Black leftist conference the themes would have been systemic racism, the Anthropocene, environmental justice, reproductive rights, reparations and restorative justice, mass incarceration, instantiations of the concept of the Black diaspora, Black feminism, the Black LGBTQIA, and the necessary annihilation (and rampant destructiveness) of capitalism.

This conservative conference engaged virtually none of that, except perhaps to mock it as one speaker who dismissed transgenderism by telling everyone to read Genesis 1:27; or to deny it as former federal appellate judge Janice Rogers Brown intimated that there was no indication of racial bias in imprisonment. (She also deplored soft-on-crime policies as “outrageous” and prosecutors who pursued such policies were not honoring their oath of office to uphold the law.) There was no mention of climate change, systemic racism, abortion (I suspect most people there were not in favor of its broad legalization), a Black diaspora, Black feminism, or any of the Black left’s favorite hobby horses.

This conference offered three cheers for capitalism and economic growth; much talk about the Black father and the in-tact Black family, the nuclear Black family or, as one speaker put it, “the natural Black family”(the holy of holies for this crowd); much support for religious faith particularly Christianity and its importance in conveying useful, time-tested values sent directly by God; much support for the meritocracy, entrepreneurship, and moving beyond racism as the defining aspect of Black life.

• • •

Children, go where I send thee

…so much which we’ve gleaned through the harsh discipline of Negro American life is simply too precious to be lost.

—Ralph Ellison, “That Same Pain, That Same Pleasure”10

There was much that I liked about the conference. Nearly all the speakers were good or at least interesting. Some, of course, were better than others. Economics professor and senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute Glenn Loury, who gave the keynote address, was brilliant: incisive, poetic, scholarly, magisterial, and accessible. His explanation of the persistence of racial inequality—and the parsing of the transactional and the relational—I found less compelling than his using the speech to defend his creed. Calling himself “a man of the west” echoed how Richard Wright described himself in some of the lectures he gave in Europe between 1950 and 1956 that are collected in White Man, Listen! Wright thought this gave him a “double vision,”11 (reminiscent of W. E. B. Du Bois’s double consciousness), an ability to see the West from both the inside and the outside. I think Loury meant something like this too. To deny being a westerner and to denounce western values was tantamount to denying and denouncing himself. (This reminded me of the scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man where the narrator is trapped inside an electro-shock machine and discovers that it is possible for him to destroy the machine but not without killing himself.12 And in this way Black Americans have become indispensable to defending western values because their existence is central to the validity of those values and those values validate Blacks as Americans. Loury also called the left offering not a false narrative but “a bluff” that those in the room should call because the left had nothing to back them all (a common belief among conservatives). He said it would take courage, a word used often during the conference.

Senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-organizer Ian Rowe spoke mostly about schools. “The way we are choosing to close the achievement gap is to make mediocrity the norm,” he said. “I want Black kids to know they can do hard things.” I strongly agreed with this last sentiment. It is an article of faith we Black adults must hold for our children. We must believe in them at all costs and how we can believe in them when we think we must make easier for them in school. On the whole, he found the leftist impact on Black education unconscionable. He dismissed anti-racist education as anti-intellectual. Rowe and the other speakers had nothing good to say about the 1619 Project which historian David Kaiser called “bad history.” Rowe mocked Ibram Kendi’s definition of racism which did indeed sound like a tautology and called him “a thief.” (It might have been Loury. I am not sure.) Rowe pointed out that most White children cannot read at grade level, and this surely is not caused by racism and the gap between White children and the 100th percentile was greater than the gap between Black and White children. Racializing the achievement gap has not helped any children, he continued. He insisted that we must teach Black children “the success ethic”: finish high school, get a job to gain the discipline of work experience, get married, then have children. He said that if Black children followed this pattern, it is very likely that they will enjoy success and stability in their lives. He also spoke of a third way, to get away from the binary of Blame the System and Blame the Victim, the half-truths that added up to a total lie. His third way was Agency (also the title of his new book, coincidentally), a combination of free will and moral guidance. He said this is built on the pillars of Family, Religion, Education, and Entrepreneurship, which forms the acronym FREE. That seemed a bit too Madison Avenue-ish for my taste or a bit too much like a corny nonprofit slogan, but it neatly and effectively summed up how and where this crowd would position itself. And Rowe was an eloquent speaker. (In Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality, Thomas Sowell talks of Black thinkers needing a third way to escape the binary that Black lack of achievement was either genetic or environmental.13)

Certainly, the panel that had the most dramatic impact was Robert Woodson’s “Success on the Ground: How Local Leaders Are Reshaping Hearts, Minds, and Communities.” Woodson was something of an eminence grise at this conference. He had attended the Fairmount Conference, the only person present, other than Clarence Thomas, who had been “present at the creation,” so to speak. Founder of the Woodson Center in 1981, just one year after Fairmount, Woodson, a MacArthur “Genius” Award winner, has long been on the frontlines of getting people in low-income neighborhoods to empower themselves and their communities by solving their own problems. The four speakers on Woodson’s panel ranged from a former convict who ran an organization in Las Vegas to help felons stay out of prison once they were released; another worked with troubled youth in Louisiana that others had given up on; a former addict worked with poor communities in Jackson, Mississippi; and another is the director of Voices of Black Mothers United, serving mothers who have lost children.

All were inspirational speakers who turned the audience into an amen corner. After the director of Voices of Black Mothers United told the story of how her daughter was murdered in a crossfire between two gangs, we, teary-eyed, stood to give her a standing ovation. All their personal stories were powerful as was their commitment to their organizations’ missions. This is what is called “bottom-up reform.” I was enormously impressed with these people.

Robert Woodson was something of an eminence grise at this conference. He had attended the Fairmount Conference, the only person present, other than Clarence Thomas, who had been “present at the creation,” so to speak.

My overall impression of this conference is that it is mistaken to call the Black conservative an Uncle Tom or as interchangeable with a White conservative or as providing cover for White conservatives (as if Black leftists are not convenient tools for the White leftist agenda). When Woodson, in his introductory remarks for his panel, talked about the story of the Old Testament Joseph, I thought immediately of novelist and critic Albert Murray who argued that Blacks needed to adopt the story of Joseph over the story of Moses as the guiding myth of the race in his book, The Hero and the Blues which was published in 1973. All the rhetoric at the conference about courage, standards, merit, excellence, of American-ness, of Black American exceptionalism because we are the richest, most accomplished Black people in the world, of our being Black westerners and thus the most important voices in saving the West from its self-destructive urges: all of this was reminiscent of the language and the views of Ralph Ellison, Stanley Crouch, Wynton Marsalis, Black jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Don Redman, and Negro League baseball players of the 1920s and 1930s.

One may reasonably disagree with the views the Black people at this conference expressed. For instance, I strongly disagreed with the anti-Affirmative Action panel (that comprised an Asian, a Black, and a White) and wished I had had a copy of Randall Kennedy’s For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law (2013) to throw a few quotations at the panel. But it is the height of intellectual, cultural, and political dishonesty and irresponsibility to call these people Uncle Toms or sellouts. They can only be understood as part of a Black tradition of thought, the rise of a new Age of the Reformist Bookerites (ideological descendants of Booker T. Washington).

“Do you know that there are only 32 veterinary schools in this country,” I once told the students in my History of Black Conservatism course. “And Tuskegee has one of them. It is the only Black school that has one. Booker T. Washington really achieved something with that.” I do not think those students had any idea why I told them that.

• • •

Throwing together a conference on such short notice proved to be an adventure, to say the least. However, by some miracle, it was done…. Among those who gave talks were premiere black television journalist Tony Brown, academic scholars like Michael Boskin, and an impressive young man named Clarence Thomas.

—Thomas Sowell, A Personal Odyssey, on the Fairmount Conference,14 (italics mine)

…the idea that part of the great wealth of the Negro experience lay precisely in its double-edgedness.

—James Baldwin, “Princes and Powers”15

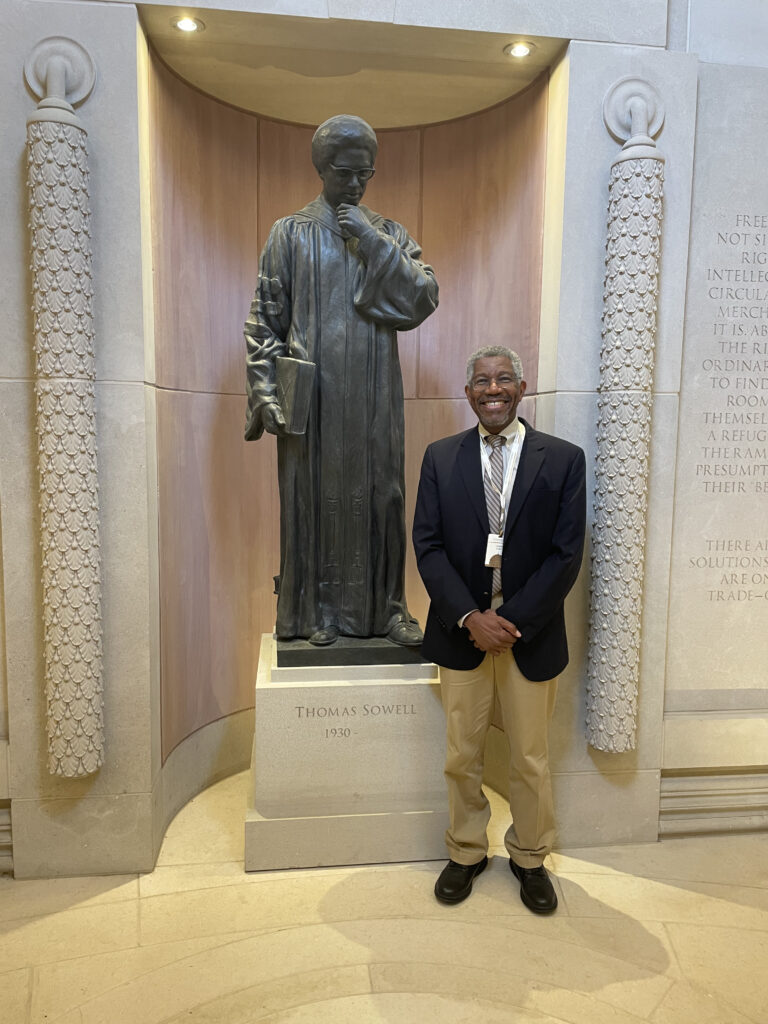

Author Gerald Early beside a statue honoring Thomas Sowell at Old Parkland during the May 12-14 Old Parkland Conference. (Photo courtesy of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas)

Clarence Thomas, the exiled prince

I have no idea why I was invited to this conference. I am not a Republican, nor do I identify as a conservative. Although I met some disgruntled Democrats and liberals, most people at conference were Republican or conservative or both. I had met both Glenn Loury and Shelby Steele before and Jason Riley had interacted over his biography of Thomas Sowell. (He interviewed me for the book, and I reviewed it for The Common Reader.) But the vast majority of the attendees (over 100 or so) had no idea who I was and asked why I was invited. I hazarded a guess in order to maintain cocktail chitchat. I told people I taught a course in the history of Black conservatism for the African and African American Studies department at my school. Jason Riley, one of the organizers, knew about this course. That, I offered, may explain it. If he invited me, I am grateful, I said, because my experience here will make the course better. They were pleased to hear this, about the course. But they asked if I had been canceled as a result of teaching this course. I said no. My colleagues approved of and supported the course. This puzzled my interlocutors.

The absence of Thomas Sowell made Justice Clarence Thomas the real celebrity of this conference. I could feel the shift in temperature, the buzz, when he entered the room during the opening cocktail reception.

“I teach in a Black Studies department. The course is about Black people. Why should my colleagues object?” I asked. I also told them, somewhat tongue in cheek, that I had been at Washington University in St. Louis for forty years and perhaps my colleagues were merely indulging an old man. I did not tell them that I also taught a course in the presidency of Barack Obama (no favorite among this crowd) and that I was floating the idea of teaching a course in the history of Black liberal thought. I see courses as the exploration of subjects, not the promotion of causes or the advocacy of cures. (There is a bit too much in the teaching profession these days of teachers trying to practice medicine on their students without a license.) But I was glad they were gratified I taught a course in Black conservatism.

On the whole, I liked the people I met at the conference. They were smart, committed to their ideas and values, and friendly to someone like me who was curious about their ideas and what they did for a living. I hope they liked me too.

The absence of Thomas Sowell made Justice Clarence Thomas the real celebrity of this conference. I could feel the shift in temperature, the buzz, when he entered the room during the opening cocktail reception. I was chatting a bit with Glenn Loury and Thomas made a beeline to him. I stood around with some others in a sort of circle as he chatted rather excitedly to Loury, whom he seemed to know well or at least well enough and, more importantly, to respect. I decided to hang around in this circle, although there was no reason for me to do so. Thomas did not know me from Adam and was not particularly interested in wanting to know me. I thought he might say something interesting about the leaked Roe v. Wade opinion or about his wife being in the news or about anything at all. It was like being a fly on the wall. He was not rude to me, simply indifferent. He talked to Loury, who had to sit because of a bad back, for perhaps fifteen minutes. But he glanced around at the rest of us standing there, so it seemed a bit as if he were holding court.

He is a dark-skinned, rotund man, a bit short, dressed in a fairly unprepossessing dark suit with suspenders. Some people came along to ask to have a picture taken with him, which he accommodated. I decided to ask someone to take my picture with him. He then seemed to notice me for the first time and agreed to do the picture if I would also include his child friend, Robert DeShay, who was, as Thomas proudly said, a National Merit scholar. They both attended Holy Cross. DeShay would talk to me later during the conference at some length about himself but what I most remember from that conversation is that he called Booker T. Washington “the Steve Jobs” of his time, which I thought was peculiar but not entirely inapt, as he explained that Washington started the National Negro Business League in 1900 and he felt its impact was considerable. Among other things, Rube Foster’s Negro National League grew out of it.) The composition was fine with me, and the picture was taken.

Next morning, in a room that looked very much like a moot courtroom in a law school, as we ate breakfast and waited for the start of the day’s panel, I found myself sitting in the same row as Thomas and two women he seemed to know. He did not pay attention to me until just as Glenn Loury was about to be introduced as the keynote speaker of the morning. He looked over at me as if he finally recognized that he had his picture taken with me the night before and the woman next to him told him I was from Washington University in St. Louis. He immediately perked up, picked up his breakfast, and sat next to me.

He seemed particularly interested in learning that I was at Washington University. He said that the way things were today that he could not speak at Washington University if some group invited him. I agreed, deploring the situation, for what is a person, whatever his or her opinions, without a voice in which he can defend or explain himself. There was a time when universities and colleges were tolerant enough to have people like George Lincoln Rockwell, the head of the American Nazi Party, as speakers.

I always found it valuable to listen to people I disagreed with because that helped to clarify my own thinking as much as listening to those with whom I agreed, and the struggle of listening to someone I disagree with is a hard discipline, as if one is learning a new power, a mastery, a new dimension of one’s own humanity. But I guess that is an old-fashioned notion these days, “so twentieth century,” as my daughter would say. I frolic with the dinosaurs.

He continued that he had lived in St. Louis for several years after he had graduated from Yale Law School. I told him I knew that, as well as the fact that he lived with Margaret Bush Wilson and worked at Monsanto because I read his autobiography, My Grandfather’s Son. I told him, further, that I used his book in my course on Black conservatism. He was, unsurprisingly, pleased to hear this. I told him that the students found his book quite interesting, as they knew little about him other than what they had heard from their parents, relatives, teachers, or whatever news sources they consulted. All of this was usually uncomplimentary.

I was impressed more by the fact that there was a statue of Sowell than by the statue itself. Thomas took some photos of me in front of the statue. At lunch, he invited me to sit next to him at the reserved table. I think it was this that probably made others think I was his friend.

After reading the book, they came away with a deeper understanding of him. He gave a hearty laugh and said that he never had any problems with Blacks who knew him and, for lack of a better term, everyday Blacks responded well to his life story. I nodded saying that this was good to know and my experience as a teacher bore this out. I did not add, however, that while some of the students became more sympathetic to him as a result of reading the book; for others, the book simply confirmed or justified their antipathy. Not everyone was won over. “Won over” is too strong an expression. Most went from hating him to feeling ambivalent or unsure or to being somewhat sympathetic. They were all glad to have read the book because he is, after all, an important man, whom they all knew, an acknowledgment that was perhaps the most significant victory for him.

He wound up staying in my company for the next several hours, so much so that later in the day people asked me if I was a personal friend of Thomas, even Jason Riley. I told everyone that I had only met him the night before.

I liked Thomas instantly. He seemed a gregarious man with a hardy laugh and a great deal of nervous energy. There was something about him that was quite down-to-earth. He was unpretentious to the core. He reminded me of my favorite uncle of my childhood. Probably because of all the hostility he has had to endure in his public life, he seems a man who really appreciates being liked and appreciates liking other people, if he can.

We continued to chat for the rest of the morning. At the lunch break, he was eager to show me the Thomas Sowell statue, so I went with him to see it. He seemed fairly familiar with Old Parkland. I suppose he has been here at least a few times as it hosts a number of conservative conferences such as this. I know Thomas had come in early February, the time this conference was originally scheduled to take place. Bad weather across a wide swath of the country, prevented most people from attending but Thomas managed to make it to Dallas and give a dinner presentation to about the thirty or fifty people—depending on whom I talked to—who were there. He also, I was told, went around and spoke personally to all of them. As I said, he is gregarious.

I was impressed more by the fact that there was a statue of Sowell than by the statue itself. Thomas took some photos of me in front of the statue. At lunch, he invited me to sit next to him at the reserved table. I think it was this that probably made others think I was his friend.

He told the table how he and his wife had a private lunch with President Trump that he enjoyed. He found Trump to be a very accessible, cordial person. This did not surprise me as all successful politicians can be charming, having mastered how to make their guests feel at ease. Thomas was honored by the occasion as one would expect him to be. I do not recall much other talk about Trump at the conference. I do not recall any of the speakers mentioning him, as least, not directly.

Probably because of all the hostility he has had to endure in his public life, he seems a man who really appreciates being liked and appreciates liking other people, if he can.

Hoover Institution fellow Shelby Steele, one of the four conference organizers, was the luncheon speaker and I noticed how struck Thomas was with him, how affected he was by what Steele said about how Blacks “reinvent their oppression” and that they do not know how to be free. They must learn to accept that they are free. They are suffering from “the shock of freedom.” (All of these formulations can be found in Steele’s most popular book, The Content of Our Character, named after the famous Martin Luther King Jr. circumlocution that has become a cliché and a rhetorical flashpoint about racial progress for the left and the right.) Steele in effect was paraphrasing Sartre: Blacks are condemned to be free, as everyone else is. What was implied in this or what I read into it was that Blacks were so conditioned to processing reality through their oppression that the absence of that oppression was not, in their minds, freedom but nothingness. Thomas quietly repeated some of Steele’s phrases as Steele said them. He was enormously impressed. He thought Steele a great thinker. As Steele was the only true, pure humanist among the organizers at the conference, this said something about how humanistic thinking is still important to people. Steele concluded his talk by relating an Albert Camus story called “The Guest” from Camus’s collection Exile and the Kingdom (1957), a reminder that he had once been a literature professor, as an illustration of how people will reinvent their oppression or their imprisonment. I told Steele later that he sounded a great deal like a French existentialist with his concerns about freedom, taking personal responsibility for your life, the issue of authenticity and the like. I am not sure if he bought it, but he thought I knew a lot about French existentialism. I did, sort of, a long time ago. I was not surprised that Thomas was impressed with Steele. Thomas’s undergraduate major at Holy Cross was English literature.16

He told me about meeting Thomas Sowell and how important that was to him, finding someone whose thinking gave shape to his own. He spoke of attending the Fairmount Conference, of how Juan Williams had outed him as a conservative, and how that changed his life in Washington, and not for the better. He was upset how the press attacked him for what he said about his sister being on welfare. “I did not see any difference between saying that she was damaged by welfare than if I had said she was sick with cancer. They wouldn’t have attacked me for that.” I responded sympathetically to all of this. I felt bad that he was still wounded by this.

I did not know, at first, quite what to make of my time with Thomas. I decided not to make much of it. Conference friendships, like shipboard romances, are purely a matter of accident, of coincidence, even of convenience. It seemed a bit of a privilege to have spent such one-on-one time with this important man. I liked him, which, on its face, should be a completely non-controversial statement. But it is not to his legion of enemies, those who loathe him. It signifies to them that I somehow approve of him and his political views. I make no unpersuasive case that somehow I approve of the person but not the views. He is his views. They come as a package, as he makes clear in how he presents himself. When he responded to Thomas Sowell’s paper on education at the Fairmount Conference, he simply related the history of his own schooling.17 (His response also indicated how in awe he was of Sowell.) His biography is his political views. His being a conservative is natural, to use a word, a word, in fact, that Black conservative George Schuyler used to describe Black people as inevitably conservative.18

I liked him not in spite of his views. I liked him, in part, because of them. His views, in one sense, are irrelevant to me. They are as shoddy as my own and everyone else’s. I liked Thomas, and I have felt this way about many such people, because of what his views mean to him, how much he feels he has had to pay to have them, how crucial they are to what his feels his life means or what he hopes that it means, how invested he is in the hope that his views justify his life. There is an anguish and an expectation, even a naïveté, in that that touched me. That we are both Black meant something to me about understanding how a Black person could feel this way. After all, the people who hate him are not irrational; they do not hate him for no reason or for no good reason. So, it is hard, particularly for a Black person, for one’s life to be a war, in this way. Sometimes as a Black person you wish people, Black and White, would stop trying to make you the Black person they think you should be and simply leave you alone with the feeble truths you have managed to uncover and the errors that you have earned the right to make.

I liked Thomas, and I have felt this way about many such people, because of what his views mean to him, how much he feels he has had to pay to have them, how crucial they are to what his feels his life means or what he hopes that it means, how invested he is in the hope that his views justify his life.

A week after the conference, at a garden party, I ran into a prominent Black St. Louisan, a newspaper owner and art collector. A man that I and the city and its patrons have long admired. As we chatted, out of the blue, he mentioned Clarence Thomas and how there was something more than his mere conservativism that bothered him about the man. I think he wanted to suggest how Thomas’s conservatism represented not a set of convictions truly held, which I think he felt he could accept, even respect, but a character flaw in the man. I started to say that I just met Thomas and what it was like to meet him. I do not know if I wanted to defend him, to explain him, or only to say what it was like to meet a celebrity, an important man. Maybe I wanted to say that everybody’s political ideology is a character flaw because it justifies our hatred as a defense against being hated. But I suddenly resigned myself. I said nothing at all. What was there to say? People think what they feel they must think. I let the moment about Thomas evaporate in the flow of the conversation. Thomas went away as abruptly as he appeared. Marlene Dietrich’s character was right when she said at the end of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil: