“Sometimes it seems as if I have spent the first half of my life refusing to let white people define me and the second half refusing to let black people define me.”

—Thomas Sowell, quoted in Jason Riley, Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell (223)

“The current militant rhetoric, self-righteousness and lifestyle are painfully old to me. I have seen the same intonations, the same cadence, the same crowd manipulation techniques, the same visions of mystical redemption, the same faith that certain costumes, gestures, phrase and group emotional release would somehow lead to the Promised Land.”

—Thomas Sowell, quoted in Jason Riley, Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell (64)

Books and the bruiser

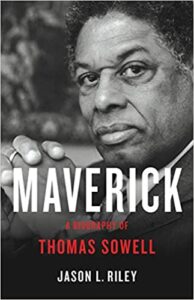

When Jason Riley called to tell me some months ago that he was writing an intellectual biography of the famous economist, Thomas Sowell, I was mildly surprised that this had not been done already. Sowell, after all, has published over fifty books in a career spanning from 1971 to 2020 (his latest book is Charter Schools and Their Enemies published on June 30, 2020), a level of production virtually unmatched by anyone in any field. Sowell was 90 when he published his latest book, so his acuity and energy is abiding. (Historian Jacques Barzun published From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life in 2000 at the age of 93. Sowell may manage to beat that if he remains productive and can live to 94.) It would be reasonable to think someone had beaten Riley to the punch. Sowell, whether one agrees or disagrees with his major ideas, is a significant presence in American academe.

The fact that Sowell is Black makes him, in a sense, even more worthy or certainly should make him even more of a subject of curiosity, if only to ask the question: how and why would a Black man sustain himself as a well-known intellectual for so long, particularly when, as Riley points out in Maverick, he has been so unpopular or unliked among most Black academics and most of the Black elite?

Even having spent most of his career, since 1980, as a research fellow at the Hoover Institute at Stanford, freeing Sowell from professorial duties like teaching, grading, chairing dissertations, evaluating faculty, and attending faculty meetings, (and putting up with the aggressive egotism and petty politics), no one could reasonably expect this amount of scholarship and polemics no matter how much drive and ambition the person possessed. Sowell’s works range from economic theory (e.g., Say’s Law: A Historical Analysis, 1972, and Marxism: Philosophy and Economics, 1985) to economic and intellectual history (e.g., Knowledge and Decisions, 1980, Migrations and Cultures: A World View, 1996, Conquests and Cultures: An International History, 1998, Intellectuals and Society, 2010), a volume of personal letters (A Man of Letters, 2007), a personal memoir (A Personal Odyssey, 2000), a primer on economics (Basic Economics: A Citizen’s Guide to the Economy, 2000, his best-selling book, having gone through many editions), and volumes collecting his long-running newspaper column (e.g., Ever Wonder Why? And Other Controversial Essays 2006, Controversial Essays 2002, Is Reality Optional? And Other Essays, 1993). This is just a sampling of titles from a varied and hefty oeuvre.

There is, of course, repetition in the themes that interest him and even in the examples he uses, but on the whole most of his books offer his audience a fresh reading experience and at least a somewhat different angle on his particular intellectual preoccupations. The fact that Sowell is Black makes him, in a sense, even more worthy or certainly should make him even more of a subject of curiosity, if only to ask the question: how and why would a Black man sustain himself as a well-known intellectual for so long, particularly when, as Riley points out in Maverick, he has been so unpopular or unliked among most Black academics and most of the Black elite? Perhaps the dislike, even hatred, most Black academics feel has driven Sowell’s production as a form of defiance? “I can be ignored,” book after book might be saying, “But I will not be silenced.” Sowell has forthrightly challenged his critics and detractors with the sheer volume of his work. In the blood sport of academic disagreement, that production is the sign of the bruiser. Whatever the reason for the neglect of Sowell, Riley provides us with a much-needed book.

Cobra and the making of the mongoose

Maverick gives us a brief biographical account of Sowell’s life, his birth and early life in North Carolina, his arrival in Harlem at the age of nine, his varied work experience after he dropped out of high school. He served in the Marine Corps during the Korean War and used the benefits due him from the G.I. Bill to return to school, first at Howard University and then Harvard. He earned his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago in 1968, right at the time when affirmative action in college admissions was beginning. He takes pride in having earned his degrees without the stigma of preferential admissions policies. Clearly, he was exceptionally bright and a grinder, both necessary for a highly successful scholar.

He had a thriving, if peripatetic, academic career, teaching at Cornell, Howard, Rutgers, Brandeis, Amherst, and UCLA. He earned tenure, the brass ring of the academic merry-go-round. He was a demanding teacher, which, unsurprisingly, made him unpopular with some students. He did not give breaks and did not accept excuses from his students who failed to do the work. A hard case, you might say. He refused to ever turn his class time over to a discussion of current events (e.g., the Vietnam War, racial violence, the election, etc.) for which he is to be respected because, after all, he was hired to teach economics, not newspaper headlines. It is assumed because he studied at Chicago under Milton Friedman and George Stigler, that he would be a free-market economist but he arrived at Chicago in 1959 as a Marxist. What moved him away from Marxism was less his schooling as it was his experience working for the government in 1960 when he saw that the mandated minimum wages for sugar workers in Puerto Rico led to greater unemployment. The government employees who administered the wage law did not care about how the law was actually hurting the workers. Riley offers this about the influence of the Chicago School:

“Sowell would come to view Stigler and Friedman as model intellectuals, not because of any particular conclusions they reached on this or that issue but because of how they went about analyzing problems, presenting their findings, and, when necessary, bucking received wisdom. Stigler, who stood out for both his rigorous thinking and his clear writing, urged his students to test and verify even widely accepted beliefs under the assumption that the conventional wisdom was often wrong.” (33)

So, according to Riley, what inspired Sowell at Chicago was the primacy of empiricism and the necessity to be skeptical, especially of what is generally assumed to be true because it is almost certainly not going to be based on much evidence. Sowell discovered that what is true, whether among the masses or among intellectual elites, is what people want to be true or think is true or feel is true or what they need to be true. He has seen himself as a soothsayer, particularly on matters of race where he has been devoted to removing the scales from people’s eyes. Most of Sowell’s books are not on race but the race books are his most controversial and probably what he is best known for.

Sowell emerged in the 1980s as a major intellectual, something of a progenitor of Black conservatism, which for many Black scholars, is something like a contradiction in terms. What does a Black person have to conserve? is the famous (albeit, now tired) quip about Black conservatives. No Black person could possibly be conservative in any normal understanding of the term because no Black person could be in favor of the status quo, since no status quo has ever been favorable to Blacks, at least, not in the United States. White conservatism in this country is a reactionary movement largely aimed to oppose Black activism which it sees as a threat to White hegemony: a legacy that stretches from Southern planters’ defense of slavery and succession to the rise of the Bourbons and White redemption after Reconstruction to legal segregation and the terror that enforced it to the rise of the post-World War II conservative movement that was anti-civil rights movement, pro-White South Africa, and anti-national liberation struggles. Clearly, the Blacks who identify as conservative have a different tale to tell about their ideological lineage and who exactly their allies are. Their conservatism CANNOT be that conservatism. Whatever the case may be, it is said that Black conservatism, however it is understood, as we have a group of people who identify with this label, was a kind of tail-end on the tail of the dog of the conservatism of the Reagan administration. That is when it became prominent, a thing.

Overall, Sowell feels the current view of Black American life is a distortion, an obsession with Black experience being nothing more than resistance and protest (which many scholars today tend to say it is) and with Black people being consigned to the role of victim and granted a kind of moral absolution that diminishes the complexity of their humanity, the sheer scope and contradictions of it.

It is usually the case that Sowell is coupled with Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, as, for Black liberal and leftist scholars, the Gold Dust Twins of Black conservatism that came out of the 1980s. But I feel that is a grievous misreading of the era and some Black intellectuals’ relationship to the rising tide of conservatism. Sowell came to public attention at the same time as Stanley Crouch, Wynton Marsalis, Henry Louis Gates, William Julius Wilson, and James McPherson, and the re-emergence of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray as éminences grises of a Black cultural tradition. What do Black people have to conserve? It was clearly thought among noted Black intellectuals of this period that Black people had a lot to conserve and we needed to begin to do this instead of frittering away our achievement in a miasma of ignorance and indifference. However much the politics of these men varied, they were similar in their insistence on a Black tradition of excellence, the construction of a Black creative or intellectual canon, their opposition to Black intellectual mediocrity which they felt was perpetuated by White liberal condescension. They admired craftsmanship, and particularly adored standards. This was partly a repudiation of the excesses of the Black Power era, which tended to celebrate indiscipline, but also a rebuke of integration, which suggested that Blacks had no dowry of intellectual or cultural achievement to bring as a bride in their marriage to western tradition. Crouch and Marsalis wanted to codify and make classical the jazz tradition of Ellington and Armstrong as America’s great art music and to combat the idea that criminality was Black political and cultural authenticity; Gates wanted Black Studies to be respected in the academy, to have intellectual gravitas, and to be recognized for a body of work that had been neglected; McPherson represented technical proficiency in fiction writing; Wilson had broached the idea that race was not as crucial in understanding Black life and Black poverty as it had been. All of them might be called, in some broad sense, Ellisonians, influenced by the aesthetics and standards of Ellison and Murray, who believed in art over politics, dedication to the technical over the passion of militancy, Black culture as a stunning achievement, not a deficit. In this broader regard, Sowell actually fits this group rather well.

Riley makes the powerful point of how Sowell was largely influenced in his most formative years by Black intellectuals like Franklin Frazier, St. Clair Drake, John Hope Franklin, Kenneth Clark, and Sterling Brown, some of whom encouraged him to challenge prevailing Black political notions. (54) They felt that Black thinking needed some contrarians, needed some mongooses to bloody the smug, leftwing cobras. Sowell was at least in part a product of an earlier Black tradition, what was called Negro Studies, and the Black intellectual tradition that arose from the world of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Sowell’s attitude, his cockiness, his productivity, his belief in empiricism, brings to mind historian Carter G. Woodson, although, admittedly, the two men were up to something quite different as scholars. Sowell and Woodson, Frazier and Murray are the tough guys of Black intellectual tradition, the “take-no-prisoners” guys. Riley is right to connect Sowell’s iconoclasm with someone like Frazier. Sowell wound up being hated by the leftist Black generation of scholars that emerged when Black Studies came to the White university. Sowell is opposed to Black experience being reduced to the quest for civil rights or that all Black achievement is the result of civil rights and protest. He is skeptical of the valorization of protest, of social justice as an idea and a goal when people do not actually know what causes the problems they want to cure or they are not fully honest about them. He opposes reparations for slavery as not only the living paying for the sins of the dead (is guilt inheritable to justify group compensation?) but also because it is highly debatable whether the current problems with Black people can be traced to slavery. “The contemporary socioeconomic positions of groups in a given society often bears no relationship to the historic wrongs they have suffered,” Sowell asserts. (213) (For Sowell, Ta-Nehisi Coates is simply another James Baldwin whose writing is “sloppy thinking” punctuated by “rhetorical flourishes.”) (101) Sowell’s books have argued this repeatedly and he brings considerable evidence to bear in support of it. Of course, his arguments can be disputed but why have so many refused to acknowledge that they even exist? Overall, Sowell feels the current view of Black American life is a distortion, an obsession with Black experience being nothing more than resistance and protest (which many scholars today tend to say it is) and with Black people being consigned to the role of victim and granted a kind of moral absolution that diminishes the complexity of their humanity, the sheer scope and contradictions of it. He also, like the Ellisonians, loves high standards, which is why he hates affirmative action, which he considers institutionalized humiliation of Black people by making their inability to meet standards and to need allowances the most interesting thing about them. For him, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, the whole apparatus of identity politics, is just the twenty-first-century version of Jim Crow under the disguise of ethnic chauvinism as a form of self-determination.

Riley makes two other important points about Sowell that have to do with his relationship with Blacks. First, in discussing Sowell’s two opposing visions—the tragic and the utopian—of A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles (1987), Riley writes, “Those with the tragic view tend to see limits to human betterment. Ridding the world of war or crime or prejudice, however desirable, is unrealistic. . . . The opposite of the constrained vision is an ‘unconstrained’ or ‘utopian’ view of the human condition, which rejects the idea of inherent limits on what can be achieved. . . . Social problems can be not merely managed but solved.” (157-158) This construction is scarcely original (think pre-millennial and post-millennial in Christian eschatology) but what is important is Sowell’s identification with the tragic or constrained vision which so closely mirrors blues music or a kind of blues view of life, the grappling with experience, the abhorrence of self-pity, the insistence of facing reality without flinching, accepting one’s fate with humor or ironical indifference. Black radicals of the late 1960s like Maulana Ron Karenga thought blues music lacked political consciousness, was a music of resignation. It was actually a tough music that arose from the harsh discipline of being Black, a tough proposition or, as Black comedian Bert Williams put it, “inconvenient.” I think Sowell identifies with that aspect of Black experience.

The other point Riley makes is that Sowell is far more disliked by Black intellectuals than by everyday Black people, that the views that Sowell espouses are much more appreciated among the Black non-elite. (195) There is support for this: take the issue of defunding the police, which Sowell opposes. In the latest polls, Black strongly oppose defunding the police, in fact, they want more police in their communities. Sowell opposes affirmative action and that might seem to put him out of step with most Blacks. Not necessarily. Although support generally across all groups for affirmative action is high; in polls that ask if Blacks think race should be a factor in college admissions, it is found that they generally opposed it. Many Blacks might be thinking, “Why are we celebrating the 50th anniversary of a public policy that was supposed to end after only twenty years at the most if the policy is so effective and desirable?”

The roads we need are all there are

The common criticism of Sowell is that he is an Uncle Tom, a sellout, a house nigger, saying stuff to please White people, although there are, to be sure, a sizable number of Whites who do not like what Sowell has written. We liberal and leftist Black scholars who are the source of this criticism and who pride ourselves on speaking truth to power, as it were, work at White prestige universities, have endowed chairs funded by White capitalists, write books published by White university presses, win grants from White foundations, win prizes and get meritorious pats on the head from White organizations and institutions (MacArthur, Pulitzer, Mellon, National Book Award, etc.). Yet we think we are not saying something that is pleasing or acceptable to a considerable number of important White people, that we are the true contrarians. Who is fooling whom? If, as a Black person, you want true access to what this society has to offer, that will involve the “trade-off” (Sowell’s favorite word) of pleasing some Whites somewhere who can provide that access, and access has always been crucial for middle-class Blacks. Intellectuals, as Sowell notes in Riley’s book, are a special interest group and Black intellectuals who study race are a particular branch of that special interest group.

We liberal and leftist Black scholars who are the source of this criticism and who pride ourselves on speaking truth to power, as it were, work at White prestige universities, have endowed chairs funded by White capitalists, write books published by White university presses, win grants from White foundations, win prizes and get meritorious pats on the head from White organizations and institutions. Yet we think we are not saying something that is pleasing or acceptable to a considerable number of important White people, that we are the true contrarians. Who is fooling whom?

Riley does an excellent job of analyzing some of Sowell’s most important books, including a few of the highly technical economic works, and measuring their impact. It is good to know the origin story of Knowledge and Decisions and A Conflict of Visions, which I think, and I believe Riley does as well, are Sowell’s best books, although Riley made a case for Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality? that made me reconsider it as more essential to the Sowell canon than I had previously thought. For most readers, Riley’s account of Sowell’s books on race will be of the greatest interest, Ethnic America, which brought Sowell a popular audience, the aforementioned Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality?, Race and Economics, and Race and Culture. Riley is a good writer who makes Sowell’s most technical books accessible but he is also aided by the fact that Sowell’s books are generally more accessible than those of many economists. To know about Sowell’s intellectual influences and antecedents is useful and, oddly to say about an academic figure, even enjoyable.

Some might dismiss Riley’s work as that of the devotee or the admirer, as Riley himself identifies as a Black conservative, although one can do worse than be a sort of Boswell to Sowell’s Johnson. Nonetheless, the naysayers might ask where are the hard challenges to Sowell concerning:

- The concept of racial capitalism and how free markets are indeed racialized.

- Critical Race Theory which asserts that since this country was founded on the concept of White nationalism—something no one can deny (Hitler saw America’s racial legal system as a model for Nazi race laws)—and thus the entire ideological premise of the country was designed to oppress and exclude Blacks as they were not defined as citizens or even people.

- How could any Black scholar be conservative as it would mean defending some notion of inequality as inevitable and even preferable, for that is what conservatism comes down to, the defense of some form of inequality as fairness which seems like Bizarro thinking.

- The idea that American slavery was unique as chattel slavery, profit and loss, philosophically and politically justified dehumanization that created the damaging intellectual concept of racism that makes this slavery different in kind from all the thousands of years of slavery that preceded it.

Such a debate over such ideas between Sowell’s supporters and his detractors would be positively thrilling. I very much hope that Riley’s next project will be a collection of essays by noted scholars and intellectuals, mostly, though not exclusively Black, who will do battle over these and other challenges. I would love to read such a book, would love to read what Sowell himself would say in response to some of his detractors. Such a book would be one way to get some Black scholars who have refused to engage Sowell to do so. Riley has a legitimate concern about lack of engagement on the part of Black scholars. Are they intimidated by the empiricism or do they hold Sowell in contempt? Get some of them to write essays to explain themselves. It would serve as a vital companion to this one. But Maverick is a first important step, filling in part of our American intellectual heritage, our Black American intellectual heritage. I hope this will launch more studies of Sowell.

Riley has a legitimate concern about lack of engagement on the part of Black scholars. Are they intimidated by the empiricism or do they hold Sowell in contempt?

On my disorganized bookshelves, Sowell sits next to Eric Williams, Walter Rodney, Frazier, a biography of John Quincy Adams, Benjamin Quarles, Ann Petry’s children’s biographies of Tituba and Harriet Tubman. I have never been good at categorizing things. But you learn more from multitudes than from factions or fractions, from random association than from category. “Spark the discipline!” I always say. I must have been told this long ago by someone much smarter than anyone I have ever met.

As my mother used to tell me when I was a child, “All roads lead to Rome, Jerry.” Even the long, hard roads, the circuitous roads. The mud. The mud. Even the wrong roads, the roads that do not seem to go anywhere, I thought. She cannot mean those. Not the wrong roads. Not the hard roads. Not the mud. Not the rocks. Not the icy roads. Not the unfinished roads. Not the bruising, punishing roads. Surely, only the easy and the sure, the roads you know. The sensible roads. The roads everyone else takes. The roads people tell you to take. Those, not the others. “And all roads must be taken,” she always added.