(courtesy Emily Smith)

Back in 2021 I wrote a piece about First Lieutenant Amy Nickles, an American army nurse from Georgia who was awarded the Bronze Star in World War Two and saw as much or more of the European Theater as famed writer Ernie Pyle. I became interested in her because I could find so little about her life other than a mention by Pyle when he was in North Africa, along with the announcement of the medal and slight information from a relative.

This week I got a message from a woman in North Augusta, South Carolina, across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia, where Amy Nickles had lived in the Georgia War Veterans Nursing Home at the end of her life. Emily Smith, a Navy vet, and her husband, who is active-duty Army, bought a house in North Augusta in 2022 with the plan to renovate.

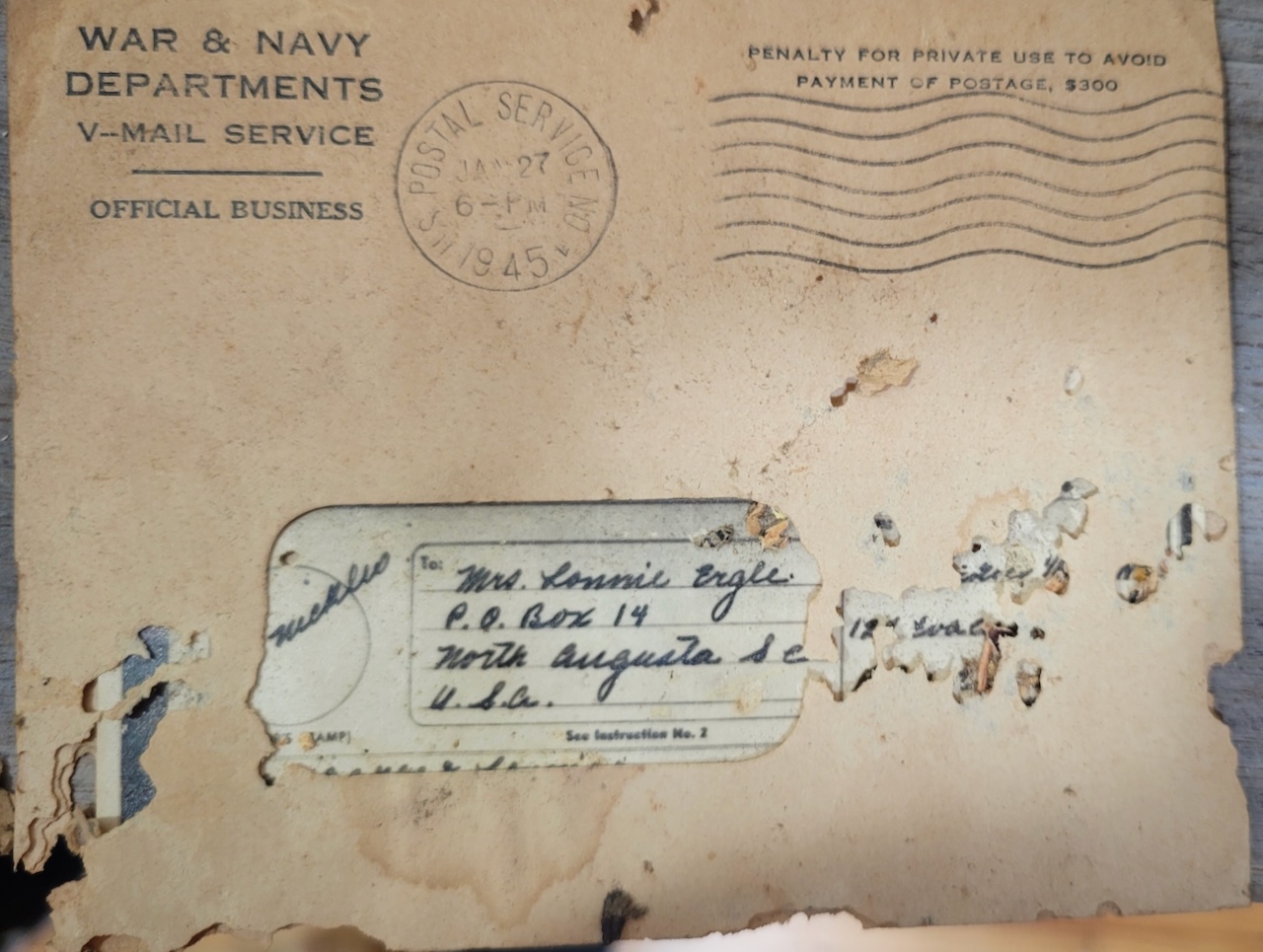

“We were tearing out the original built-in China cabinets in the butler’s pantry (they needed to go) and found [a letter] between the walls back there,” Emily told me. It was written by Amy Nickles in Belgium on January 15, 1945, and sent to the former residents of the couple’s house, Lonnie and Agnes Engel.

“At first I was just excited to get potential names for the original homeowners,” Emily Smith said, “but after looking her up and finding your article, curiosity got me digging for more information about this nurse who had clearly done amazing things. She wrote of Christmas dinner and bad weather, but also was someone who had probably seen horrible things.”

The letter was V-Mail, as it was called, for corresponding with service members overseas then. It was strict in its single-sheet economy, as letters were photographed then shipped on microfilm and printed on the other end. Add the need for operational security, and the handwritten letter has a pinched but personable tone.

“[H]ope you had a grand time [at Christmas],” Nickles writes, “not as much with us as we were very busy and still are. […] The weather has been quite disagreeable lately has snowed most every day the past week and very cold, hope this new year will be a grand one for us all and bring an end to this war, and the girls and boys to the USA.”

Nickles had been awarded the Bronze Star on October 16, 1944, but she does not mention it. The Battle of the Bulge had been raging in Belgium since December 16 and would continue until January 28, and the “very busy” must have been an utter hell of surgical care for wounded and dying soldiers. (Ernie Pyle, who was exhausted from covering the European Theater, was en route to the Pacific Theater and had three months to live.)

After I talked to Emily Smith, I checked Find A Grave again for mention of Lt. Nickles. When I wrote my first piece I did not find anything there. This time, I found a page for her with a lot of information, including her birth (1904) and death (1974) dates, and the names of her parents and siblings. There was also a 1944 article about her receiving the Bronze Star, from (presumably) the Augusta Chronicle. The article corrected a mistake in the Army captioning of the event photo; the person I thought was Nickles was not. It also claimed she was the first army nurse ashore at Normandy on D-Day, which I cannot confirm; the article has at least one contradictory error.

The man who had uploaded the article was Amy Nickles’ great-nephew, Steve Balkcom. We spoke by email.

“Amy Nickles was an older sister of Clara Bell Nickles Templeton, a sister-in-law of my grandmother,” Balkcom told me. “I’d never even heard of Amy until her great-nephew, who is also my distant cousin, sent me much family info by text a couple of years ago. He is Jonathan Welch in Augusta, GA.”

I caught up with Jonathan by text today as they drove from Savannah to Augusta. He is sixty-three and remembers Amy Nickles, mainly from her living with his family “for several months when I was 8-10 years old.” She was kind and sweet, he said, “but you could sense toughness.”

“We called her Aunt Lois,” he said, though she was his maternal grandmother’s sister. She had diabetes then and gave herself insulin shots, which “amazed” the kids, he said. He surprised me when he said she had a prosthetic leg, “which back then weighed a ton, and she would lace it up.” We discussed whether she had lost the leg in the war, and he said he thought he was told as a child that it was injured in the war, got infected, and gangrene set in, but that that could be inaccurate.

(I filed to get her military records from the National Personnel Center archive here in St. Louis, but a 1973 fire destroyed 16-18 million military records of that period, so they may not exist. Among other things, Jonathan told me that to get her name added to the local veterans memorial he must have her discharge papers. He stressed again that he believed she was the first army nurse to land on Normandy Beach.)

After a long conversation he surprised me again: “Oh, she had a glass eye, too,” he said. “I think she may have took it out in front of us too! lol.”

“She obviously liked children because I can still remember her smile when we interrogated her.”

Eventually Amy Nickles was placed in the Georgia War Veterans Home in Augusta. “I can remember Aunt Lois looking out the window at us when we left one time and feeling extremely sad that she was there,” Jonathan said.

“Just realized she looks an awful lot like my mother in that pic [at the Bronze Star ceremony].” His mother retired after forty-nine years as a research chemist at the Veterans Administration and the Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center in Augusta. She worked to the age of seventy-nine “and passed 3 yrs later I believe. Barely used any of her retirement.”

Emily Smith tells me she and her husband plan to drive out to Amy Nickles’ grave in Edgewood Cemetery in Greenwood, South Carolina, this week, about an hour each way by car.

“I guess [the letter] tugged at me personally,” she said.