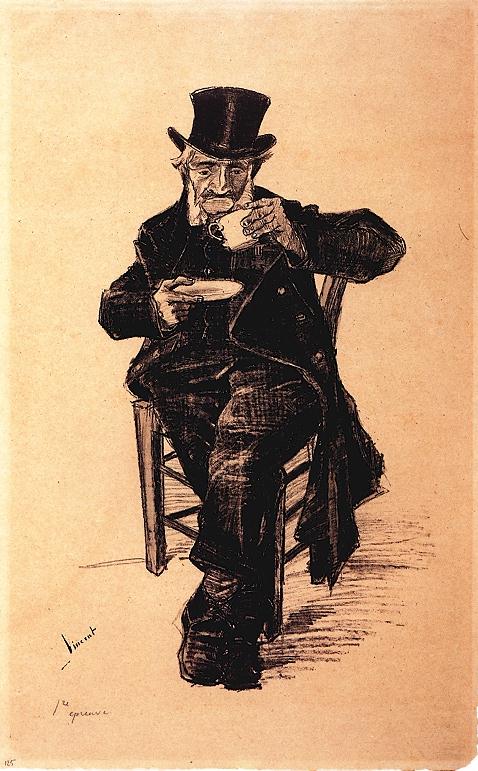

Van Gogh, orphan man with top hat, drinking coffee. Public Domain (per Wikimedia)

“Walking-around knowledge” is an odd phrase. Do you use it? I do not know where I first heard it, though I suspect it was in my childhood or army service because it feels like an older construction my elders would have used. The presumption was that seeing and hearing things firsthand—to include conversation with locals, who told you things you could trust, or at least you knew well enough to know they were liars—was preferable to knowing in other ways.

There is not much mention of the phrase online and none at all in the reference books I have at hand, such as the Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. My edition of The Compact Oxford English Dictionary does not seem to list it, though there are echoes. Etymology is often a matter of hearing the practical bases of metaphors.

From Sporting Magazine, 1802, the OED reports: “Your provincial news must take in all the bye races [cricket, perhaps], cock matches, ‘walking-goes, and every thing that’s worth knowing.’”

Contrast this with a phrase attributed first to Lytton, in 1835: “Heaven deliver me from the proximity of a walking dictionary….”

The distinction between “street knowledge” and “book learning” continues and is wrapped even more in the political now. Consider the cry of 10 million aging men on Facebook: “I went to the College of Hard Knocks.”

As I feel out my personal definition of “walking-around knowledge,” I do think of the commonsensical: “ice cream is cold,” for example. But did you catch the furor over Walmart ice cream bars never melting, even in 100-degree heat? People argue now over the very meaning of “food,” for good reason.

Feeling sure that you know something is not always the same as knowing something, and “common sense,” a near-synonym for foundational, walking-around knowledge, can become a worldview with its own elements of snobbery and anti-intellectualism.

Walking-around knowledge can also be seen as capacity—a scaffolding that permits deeper thought. The Newark Board of Education, which subscribes to E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge system, says on their site, “[Y]ou probably take for granted how much ‘walking-around knowledge’ you carry inside your head—and how much it helps you. If you have a rich base of background knowledge, it’s easier to learn more. And it’s much harder to read with comprehension, solve problems and think critically if you don’t.”

I cannot help but think of moments from my own life that showed the limits of walking-around knowledge. Long ago, for instance, I was taught to toss apple slices in lemon juice to keep them from browning. I saw it worked well. For years I failed to understand that any acid, such as cider vinegar, will also do the trick. This failure of understanding comes from sticking too closely to the personally-experienced. I have written elsewhere about other examples.

Or take the seeming virtue of being on time—drilled into me by politesse and the army, so that even now I say proudly to my kids and friends as we arrive somewhere after a complicated period of getting ready and driving, “On time, on target!”—which turns out is not a universal good. Ever get pressed into labor in your dress shoes because you were the first one at the party? This failure of understanding comes from lacking the imagination to anticipate the consequences of actions.

In the digital age, something strange has happened to people’s perceptions of their own walking-around knowledge. Perhaps they feel the walking-around has been accelerated and covers more ground. Many have surety these days, which they attribute to their “research” online and a worldwide web of never-met acquaintances, who are at best the virtual equivalent of the guys who sat around drinking coffee every morning at the Hardee’s in my hometown. Hooper was kind of funny, but if he is still alive I would not take his knowledge of Taylor Swift and make it my own.