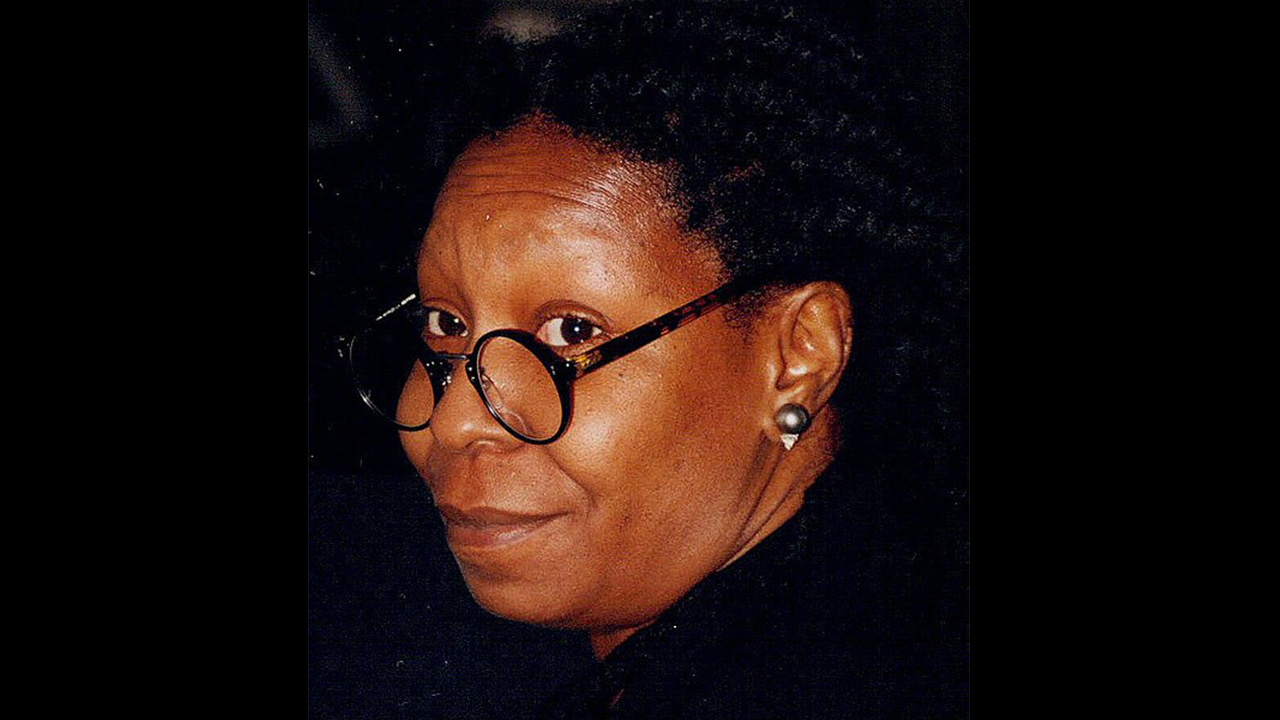

Whoopi Goldberg in 1996. (Wiki CC photo via Flickr by John Mathew Smith & www.celebrity-photos.com at https://flickr.com/photos/36277035@N06/46383818011)

“The tension between Negroes and Jews contains an element not characteristic of Negro-Gentile tension, an element which accounts in some measure for the Negro’s tendency to castigate the Jew verbally more often than the Gentile, and which might lead one to the conclusion that, of all white people on the face of the earth, it is the Jew whom the Negro hates most. When the Negro hates the Jew as a Jew he does so partly because the nation does….

At the same time, there is a subterranean assumption that the Jew should ‘know better,’ that he has suffered enough himself to know what suffering means.”

—James Baldwin, “The Harlem Ghetto”¹

Whoopi Goldberg’s remark about the Holocaust being an essentially White-on-White crime has been rightly criticized for being the monumental error that it is. (She has apologized twice.) But in that criticism is also an element of misunderstanding that lies at the foundation of the relationship between Blacks and Jews. The only thing I found surprising about Goldberg’s comments was how familiar they were, for I heard many Black people speak similarly since my boyhood. Such a view arises from the Black American’s experience with American Jews and the identity that each group has in this country. It has nothing to do with either the Holocaust, Nazi ideology, or the persistence of virulent antisemitism in European history, profoundly and accurately characterized as the longest hatred.

From the Black American’s perspective, Jews have an enormous advantage in the United States because they can be considered White, by appearance, the word that Goldberg stressed in her remarks. She judges race by appearance which is how it is often determined in the United States, the one-drop rule notwithstanding. The most quoted line in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” (emphasis mine)

In other words, he dreamed of a world where his children would not be judged by their race, their appearance. King may not have thought that race was completely reducible to appearance but it accounted almost exclusively for how Blacks were treated.

There are Black people who have passed for White, of course, but this is because they appeared White. The vast majority of Black people, no matter how assimilated many may be or how much they may identify with White values or White perspectives, can never be White because they do not look White. Appearance is the simplistic purity of Whiteness. Jews may be the most hated people on Earth, but Blacks feel they are the most stigmatized and degraded. This is a distinction that bears an extraordinary difference in how these two groups see themselves and each other. Both are seen as subhuman, but the Jews are feared for what they can do, their success; Blacks are held in contempt for what we cannot do, our failure.

How else are Black Americans to feel about the epistemology of race as they are condemned by their appearance, an appearance which they cannot change no matter what they may believe or how much some may decide they want to worship Whites and their culture? In short, in the eyes of Black Americans, Jews have the ability to “pass” as White, to be assimilated in ways that Black Americans feel they cannot. (To Blacks, Whiteness is the huge assimilation machine for European ethnicities and races. I remember hearing an Israeli scholar on one of the two trips I have taken to Israel say that the biggest fear he had for Jews in the United States is that they would be assimilated out of existence. For Blacks, that is an alien fear.)

To be sure, whatever can be said about the vast ethnic and racial variety of Jews in the world, Black Americans have experienced Jews as White, as of European descent, in this country. In the eyes of Blacks, Jews could still escape being Jewish or being seen primarily as being Jews.

This was a sore point with some Blacks, such a young Black teenage friend I had, a bright lad I was fond of. “Militant,” he was, as they called Black folk of a particular temperament in those days. At the time of our friendship, I was attending a predominantly Jewish high school. I had several Jewish friends. One day, it must have been in 1967 as the subject arose because we had been discussing the Arab-Israeli War, he told me to be careful about being so friendly with Jews.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because they’re White people, just like the rest of them,” he said, “They want to act like they’re your friend, but they are White people too.”

“No,” I said, “They’re different. The Whites in Europe have tried to kill them. If they are just like the other Whites, why did the Europeans want to murder them all.”

“You ever heard of Judah Benjamin?” he posed.

I shook my head. It was the first time I had heard the name. “Who the heck is Judah Benjamin?”

“Judah Benjamin was the vice president of the Confederacy.² He was right up there with Jeff Davis. He was a lawyer who defended slavery and he owned a lot of slaves. And he was a Jew. So, don’t give me that crap about how they’re different from other White people. If they so different, how come this guy could join the Confederacy? It wasn’t like they didn’t let him join ’cause he was a Jew. You can’t trust them any more than any other White people. They’re worse ’cause they can do just what this Judah Benjamin guy did. Blend right in. I don’t know about what happened to them in Europe, but I know they can blend in here, just like Benjamin did. Can you blend in?” he smirked.

I was hardly in a position to challenge him. I knew precious little at the time about the Confederacy and nothing about Benjamin. I could only lamely reply, “My Jewish friends aren’t Judah Benjamin,” which was about the same as saying, “There are good Jews,” similar to a White of a certain era saying, “There are good Negroes.” He just waved his hand. Little did I know that my friend’s attitude would become the basis of a major movement in the Black community when, in 1991, the Nation of Islam published The Secret Relationship Between Black and Jews, meant to “redefine” how Blacks viewed Jews. By then, of course, I knew who Judah Benjamin was and a lot of other things as well.

Indeed, Jews seem, to the Black American, to have the best of both worlds in the realm of identity: Jews can cease to practice their religion and still be Jews, still identify as Jews; yet people can convert to their religion and become Jews. Jews have a native land, a native language, a crucial book (to all humanity) that outlines their history and destiny as a people. Black Americans have had to scramble for any semblances of these markers of identity, have had to improvise, collage together the flotsam and jetsam of their ravaged existence. The antisemitism Jews have faced in this country has not prevented them from protecting their identity, nor from thriving as a people, much to their credit. But it should be also stated that they came to this country as migrants because they thought they could protect their identity. Blacks came to this country as forced laborers, to have their identities erased, to be all the more effective tools for their White masters’ will. Jews were exiles; Blacks were orphans. This is another difference between the two groups that must be grasped to understand what they say about one another.

Doubtless, Jews have certainly struck Blacks as a different kind of White people, in some instances, decidedly different. Jews have played an important role in the dissemination of African-American music and culture, in the development of Black intellectuals and scholars, in their interest in Black people as people and as Blacks. Jews have supported Blacks in our civil rights struggle, even died in it. But this interest and support have been a source of chafing because of what Blacks feel has been a lack of parity because, in part, the American Jew is White and, in part, because the Jew has the advantage, as Blacks see it, of being Jewish, an identity which has some considerable strengths that Black people lack. Jews could influence Blacks in ways that Blacks could not influence them. Jews in Hollywood played a significant part in shaping the negative image of Blacks in films for decades before partnering with Walter White of the NAACP to change things. In the American power game, Jews have had more of it than Blacks have had, for sure. And because of this, many Blacks feel that they were taken advantage of in their relationship with Jews.

There have been moments of sharp division as well: the fight with Jewish teachers and a Jewish-dominated teachers union over Black control of public schools in Ocean Hill/Brownsville in Brooklyn; the firing of Andrew Young when he served as ambassador to the United Nations under Jimmy Carter; the rise of neoconservative Jews and their opposition to affirmative action; the rise of Louis Farrakhan and his impact on Black public opinion; the increasing tendency of a Black intellectual class to be supportive of, even closely identifying with, Palestinians, and staunchly anti-Israel, although Black people’s evangelical Christianity will limit, in some measure, how anti-Israel the group itself becomes.

On the other hand, Jews might have a right to be suspicious of Blacks, of an underlying of antisemitism in us, as we are, after all, as an especially devout group, overwhelmingly Christian, a religion with built-in antisemitism; we are also the most likely Americans to convert to Islam, and it has been segments of the Black American Muslim community that have, in recent years, been most antagonistic to Jews, purposely baiting them. We are among the most likely groups of Americans to identify with the Third World, to support the idea that Zionism is racism. They also have a right to be suspicious as we claim our innocence of it. Many Black people believe that they cannot possibly be antisemitic no matter how anti-Jewish or offensively ignorant some of our opinions may be. This is the pure innocence that derives from being a victim of systemic oppression. What harm can little ole powerless me do to Jews? Alas, what harm can ignorance, prejudice, and error do to any group when expressed by anyone? To say that Blacks have less power is not to say they have none. If Blacks have a moral right, as Baldwin expressed in the epigraph to this post, to expect the Jew to know better, then Jews have the same right to expect Blacks to know better.

Whoopi Goldberg’s name, a kind of hipster-comic stage name, played upon the difference between Blacks and Jews. Who would expect a Black person to have a Jewish last name? And this joke can only work if one assumes that American Jews are White. (There is also with the name the reference to the overly complicated Rube Goldberg machine, another comic touch to accompany the simplicity of Whoopi, as in whoopee cushion.) We have the famous cases of Sammy Davis Jr. and Julius Lester, noted Black men who very publicly converted to Judaism and who have written about it. But in both cases the conversions alienated them from the Black community, despite how much Blacks tend to appreciate devoutness; they were seen as acts of assimilation, not as adoration of a particular faith. Perhaps this is because being a Jew is not simply a matter of religion. In both instances, many Blacks felt that in some way they were being rejected. What is odd here is that Blacks as Christians have historically, and deeply, identified with the Jewish story. As Baldwin writes, “The hymns, the texts, and most favored legends of the devout Negro are all Old Testament and therefore Jewish in origin…”³ Not even the rise of Africentricity, an intellectual and emotional fascination with Ancient Egypt, an identification with Pharaohs, a realignment of Black African history; none of this has diminished the view that Blacks have that they are the true Old Testament Jews of American history. In the Black community, there have been sects of Black Jews who have expressed themselves explicitly as that: Black Jews or Black Hebrews (or the original Jews). What these sects did was try to make being a Jew a way of being Black or of returning to Blackness. And certain Black Christian sects, such as the one in which singer Marvin Gaye was reared, are practically indistinguishable from Judaism.

The story of Blacks and Jews is complicated and Whoopi Goldberg, name and all, is part of that complication of affection, identification, misunderstanding, sense of betrayal, envy, and bafflement. Whoopi Goldberg is an emblem, small yet compelling, of Blacks and Jews as secret sharers of sorts, a kind of cross-fertilization. It does neither group any good to see it damaged beyond repair. The only way to reduce error is to correct it; whether that is best achieved by punishing its bearer is an open question.

• • •

¹ James Baldwin, “The Harlem Ghetto” in Notes of a Native Son, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 69.

² Judah Benjamin was actually the Secretary of State for the Confederacy. But I am certain my friend identified him as the vice president.

³ James Baldwin, “The Harlem Ghetto,” 67.