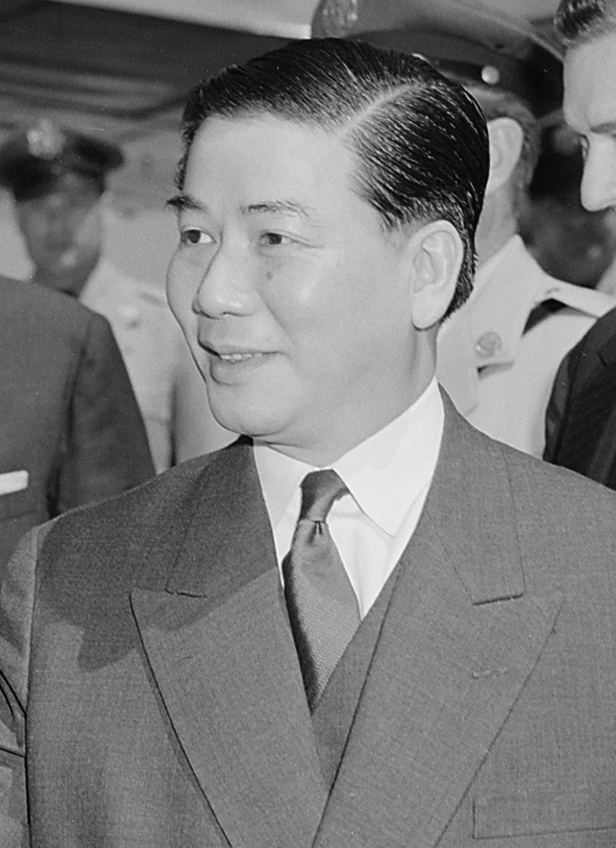

South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem

On November 2, 1963, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem was assassinated, the victim of a military coup. Twenty days later U.S. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in what was apparently another coup, although it remains unclear who wanted it and why. This is clearly what Malcolm X was referring to when he made the comment about “chickens coming home to roost” after Kennedy’s assassination. The observation so upset Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad that he suspended Malcolm, in effect, as things unfolded, kicked him out of the group. Malcolm’s own assassination in 1965, a public shooting reminiscent of Kennedy’s murder, had the air of a coup about it. The chickens kept coming home to roost.

In any case, the United States, frustrated by Diem’s recalcitrance in handling the Buddhist uprising, protesting the power of the ruling Catholic minority, and the utterly precarious political state of South Vietnam, approved the coup. Kennedy made one last-ditch effort in October 1963 to mend things with Diem by sending Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor, to Saigon. The public reason for this visit was a progress report on the war. What Kennedy really wanted to know was if there was any chance for the Diem regime. We Americans had come a long way from the 1950s, when Diem was celebrated by American politicians, called “the Churchill of Asia,” “our boy,” the Asian bulwark against communism, and all that.

Diem shared some traits with his opposite in North Vietnam, the communist Ho Chi Minh. As Monique Brinson Demery writes, “Both were from central Vietnam, and both of their fathers had instilled an anti-French, anticolonial, and nationalist ethos in their sons. Ho had even studied at the school in Hue founded by Diem’s father. Like Diem, Ho Chi Minh hoped that the Americans would help the Vietnamese in their anti-French struggle.” After WWII, Ho offered Diem a prominent job in the independent government he was trying to create. Diem, one of whose brothers and a nephew had been murdered by communists, disdainfully refused. Diem wanted America’s help to defeat Ho but feared their hegemony, which was why he became increasingly difficult for Americans to handle.

By the end, Kennedy, paraphrasing Henry II about Becket, was saying, in effect, “Can no one rid me of this miserable, stubborn, Catholic Asian strongman?” Maybe Kennedy wanted out of Vietnam, but not before the 1964 American presidential election, and getting rid of Diem was going to make that easier. Maybe Diem was even worse in the minds of the American political brain trust than the South Korean strongman Syngman Rhee, who was such a source of irritation during the Korean War. Despite Kennedy’s tacit approval to support a coup, by all reports, he was stunned when he was told of Diem’s death, “ashen” was the word. It unnerved him, at least momentarily, that it was actually done. As bad as Diem was, the leaders of South Vietnam who followed him were worse. Remarkably, Diem’s assassination made an impossibly bad situation mind-numbingly, impossibly worse. Franklin D. Roosevelt once famously said of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza, “Yes, he is a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.” No one said that about Diem. We tried to say that about the South Vietnamese leaders who followed Diem, with little conviction. Even the efficiency of brutality has its limits.

I knew nearly nothing of this as a boy. Diem was just a name to me. What I remember is Diem’s sister-in-law, Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu, the Dragon Lady as the American press called her. As Diem was a bachelor, (there were rumors that he was gay, but it was believed by many that he did not have sex), Madame Nhu was the First Lady of South Vietnam. She was in America at the time of Diem’s assassination, touring and lecturing, much to President Kennedy’s chagrin. He disliked her; thought she emasculated men. If she was to survive as a voice, a presence, in South Vietnamese politics, she had better, as a woman, be capable of, good at, in fact, emasculating men. Kennedy referred to her as “that goddamn bitch [who] stuck her nose in and boiled up the whole situation down there [in South Vietnam].” She was a striking physical presence. I thought she was beautiful and crazy. She was a figure of great controversy: outspoken, impolitic, bigoted, fashionable, clever, tough, vulnerable. She hypnotized me completely. I had never encountered a woman like her as a public figure. None of the adults around me liked her, probably because she was such a darling of the American rightwing, but were nonetheless fascinated. I cannot think of any Asian woman during my childhood who was talked about as much.

Shortly before Madame Nhu arrived in the United States, her mother secretly met with someone influential in the Kennedy administration. She informed the official to tell Kennedy to get rid of Diem and her son-in-law, as Diem was incompetent and her son-in-law a barbarian. As for her daughter, she said to the official that she told people in the Vietnamese communities of New York and Washington to run her over with a car. Madame Nhu’s mother was a highly assimilated member of the Vietnamese elite who enjoyed all cultural things French during that colonial area and attracted a Japanese lover to gain the position of foreign secretary of Indochina for her husband during WWII. It was said that Madame Nhu’s mother emasculated men too. Like mother, like daughter. At the time of Madame Nhu’s arrival in America, her father was South Vietnam’s ambassador to the United States. When Madame Nhu tried to see her parents when she came to Washington, they would not open the door. Familial dysfunction runs deep.

Monique Brinson Demery’s Finding the Dragon Lady: The Mystery of Vietnam’s Madame Nhu (New York: Public Affairs, 2013) was helpful in writing this post.