A few years ago, a literary agent told me I needed to make my murder mystery’s detective suffer more, struggle more, face more problems and threats and terrors. She had no idea she was talking to a woman who recovered from surgery by watching reruns of The Thin Man, Nick and Nora dressed to the nines and drinking champagne while they solved crimes for fun. Besides, I liked my detective. Why would I want her to suffer? I tried another agent. This one said the book needed to be “a little more Gone Girl.”

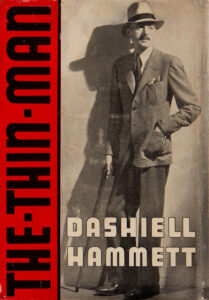

A few years ago, a literary agent told me I needed to make my murder mystery’s detective suffer more, struggle more, face more problems and threats and terrors. She had no idea she was talking to a woman who recovered from surgery by watching reruns of The Thin Man, Nick and Nora dressed to the nines and drinking champagne while they solved crimes for fun. Besides, I liked my detective. Why would I want her to suffer? I tried another agent. This one said the book needed to be “a little more Gone Girl.”

Well, Gone Girl is gone now. For seven years, book clubs across America read one “girl” book after another—girls on trains, girls staring out windows—all of them about white suburban women who could not trust, could not be trusted, or both. Domestic noir reached such a crescendo, it is a wonder anyone wed. This was the old gothic suspense with a twist: Women were still victims, but they were also quite capable of duplicity, revenge, and homicide.

I ask writer and scholar Olivia Rutigliano, who often writes about fiction for CrimeReads, what current trends reveal. Well, she replies, “as with Knives Out, many new mystery works seem to be responding very directly to the oppressions fostered by the Trump administration, and themes of misogyny and sexism that we’re observing in our current #MeToo era.”

Midcentury, only the guys were tough, and they were so one-dimensional, they were almost soothing. No crises of conscience, just scar tissue. No struggling against addictions; they just had ’em. No woman in her right mind would trust Sam Spade today, but we needed him then. Noir was the shadow cast by the shiny American dream. It reminded us of the dangers Madison Avenue ignored.

And now we have either bleak Scandi-noir or hot, bloody Latin noir, straight from the cartels at the border.

In between, mysteries diversified—about as much as the country did. White women, black men, Monk’s OCD to break up all the depressed loner alcoholics. You can tell a lot about a nation by the way it writes crime. For one thing, the books are no longer called mysteries. They are crime fiction—the emphasis on the social rupture, not the puzzle—or crime thrillers, the emphasis on the adrenaline. Life seemed simpler in the days of the mystery: It could be solved, and order restored. Now there are so many societal complications and subplots and cumulative miseries that all we expect is a modicum of closure, with a lot of ragged ends left hanging. This is, no doubt, more realistic and more mature of us (albeit far less satisfying).

Have you noticed that there are not as many American police procedurals anymore, either? Other countries still have superstar police detectives—Louise Penny’s Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, Wallander—but ours tend to be wisecracking forensic teams. Or Tom Selleck. We have lost our faith in cops, just as the world has lost its faith in clergy. The successors of Fr. Brown, Brother Cadfael, Sister Fidelma, and Rabbi Small are Episcopalian sleuths as mild as their creed.

What Americans like now is true crime. In Savage Appetites, Rachel Monroe points out that internet culture reinvented true crime, making it a self-absorbed amateur obsession. First we were all forensics experts; now we are cybersleuths. But even that enthusiasm is waning.

As Brian Phillips put it in The Ringer, “Killing, like sex and streetwear, has a trend cycle.”

Mystery writer Lori Rader-Day is not convinced of my tidy theory; she points out that “trends in publishing are really hard to pinpoint. I think sometimes the trend isn’t in what is being published but in what we as readers start to notice and find more resonance in. Then, of course, the publishing industry races to supply more of that thing, whatever it is.” Domestic noir was always with us, she points out, with “fem jeop” (females in jeopardy) themes in Daphne du Maurier and Mary Higgins Clark. But where today’s “might be a bit different is in how the women’s point of view might be, in the end, rewarded and celebrated instead of punished or squashed in the name of the status quo.”

Which seems a significant difference.

It is true that the field is wide, with cozies and retro noir and traditional mysteries always amply stocked, and certain tropes just shift a bit. Nero Wolfe stayed in his brownstone, fat and happy, drinking beer, growing orchids, and solving crimes from his armchair. Jeffrey Deaver’s Lincoln Rhyme stays in his penthouse, paralyzed and mentally restless, using science to solve crimes from his wheelchair. Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie is a contemporary reinvention of the noir hero, grudgingly chivalrous.

Still, it is hard not to note the number of spy novels coming out lately, now that we are losing alliances with so many countries and cybersurveillance and hacking are amping up the risks. The newest surge is in eco-thrillers that weave in the planet’s peril. Thrillers in general are big now, maybe because their central thrust is danger rather than mystery.

In traditional crime fiction, there is a heightened friction between law and chaos. You would think this would put us off, but interest is as palpable as ever. Crime nearly always dominates the New York Times Bestseller List, and in 2017, U.K. publishers announced an increase of nineteen percent in crime fiction sales, topping general and literary fiction.

Women are dominating, too—it is now the men who are adopting gender-neutral bylines, like A.J. Finn and Riley Sager. The women are not bothering to be nice, either. My Sister, the Serial Killer is just one of many examples of rage, and the habitual frequency of rape and stalking motifs is being sharply called into question—even though podcasts and dramas about missing, exploited, raped, abused, and/or murdered white women still top the list. “Part of the curriculum of growing up as a girl,” Monroe writes in Savage Appetites, “is to learn lessons about your vulnerability—if not from your parents, then from a culture that’s fascinated by wounded women.” Interviewing her for The Believer, Sarah Marshall remarks that “white women have learned we matter in America essentially by being pre-victims,” and Monroe agrees, calling it both curse and privilege: “Being inundated with images of what could happen to you warps the psyche, certainly, in some ways. But so does having the real troubles and victims in your community—like a lot of women who are not attractive young middle-class white women—be largely invisible in our culture.”

Stories about monsters preying on individual women are almost a distraction from all the other crimes and structures of exploitation, she adds. Just as the cultural obsession with serial killers might have been the FBI’s way of distracting us (this is David Schmid’s theory) from 1960s social and racial tensions, so we would revere the federal agents’ ability to crisscross the nation hunting serial killers.

“The thing that’s messed up about these iconic victims like Sharon Tate—the beautiful sexy dead women—is that their lives get reread as if their violent deaths were somehow inevitable,” says Monroe. “The murder stories we tell, and the ways that we tell them, have a political and social import and are worth taking seriously,” she writes. People are always killing and getting killed. But the stories we tell about why, and how, and with what consequence—tell a lot about us.