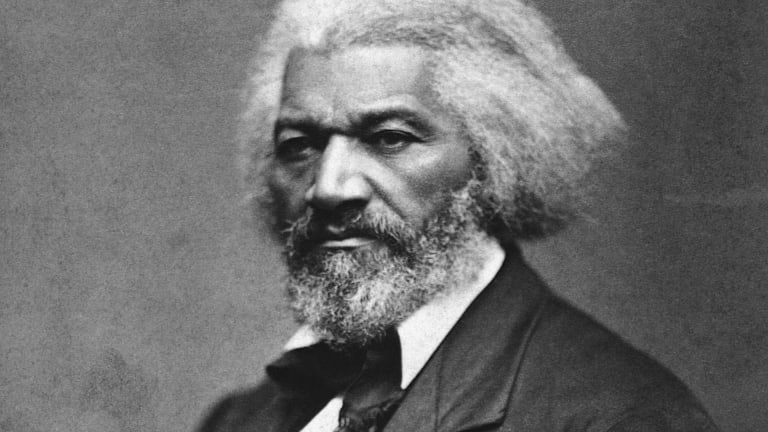

Frederick Douglass, circa 1879.

Doubtless, Frederick Douglass’s famous 1852 oration, “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July” will find itself more popular this year in some quarters than it may have been in the past. The mood of the country is fraught. There is a sense that perhaps the nation is on the brink of rebellion, separation, or complete disaster and downfall from which nothing will rescue it. Whatever power Independence Day may have had in the past to bring us together, it seems, at least at this hour, to no longer possess. (Remember one of the most popular movies of the 1990s, Independence Day, which made Will Smith a star, was about the nation coming together as one to fight an invasion from another planet. It seems quaint now.) On the one hand, we have “Fuck the Fourth” anti-commemorations, which have become an issue with the Democratic Party. On the other, we have right-wingers on the hunt to oust the insufficiently patriotic from the celebration. I do not know if even an invasion from outer space would bring us together now. More than a few might be sympathetic to the invaders and fight with them. Whether they would be rightists or leftists depends on the ideology of the alien forces.

So polarized are we now that Douglass’s words, tinged so by the impending crisis that then threatened the unity and peace of the nation—for Douglass, a false unity and a false peace—speak more profoundly or with more prescience than ever. I recall learning about his speech as a teenager when many of the young people in the civil rights movement, such as my older sisters, began to refer to it in admiration. I remember hearing journalist and activist Playtell Benjamin reciting a portion of the speech to great effect at a rally, for he was a considerable public speaker:

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice. I must mourn. to drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony….”

“What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boosted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.

I am sure that other parts of the speech were recited but this is all I can remember, probably because these particular lines were habitually quoted during my youth and even now. Indeed, I was surprised when I finally read the entire speech as an undergraduate that the second passage I quoted here was not the opening but comes about a third of the way through. I was also surprised that the speech was longer than I had imagined.

In most of the speech, Douglass, with the verve and incisiveness of a brilliant prosecutor, denounces American slavery and the country that maintains it, defends it, and excuses itself for it.

“I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just. But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, it is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more, and denounce less, would you persuade more, and rebuke less, your cause would be much more likely to succeed. But, I submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued.”

Douglass’s strategy is clear: the crimes of America in regard to slavery are self-evident. There is no need for argument but only to describe. This is, of course, the stance that many on the left—let us say those who are pro-abortion or for the LGBTQ+ cause, for instance—will take. Why should I have to argue for the wrongs committed against my humanity when they are, in fact, self-evident? “I do not wish to persuade. I have earned the right to denounce without quarter and vociferously,” they say. Whether this approach ultimately wins minds and hearts is not the point as much as it serves those who assert it as both a form of political empowerment and a sort of self-psychoanalytic clearing and cleansing. This militancy is a way to foreclose being labeled a neurotic in search of a cause. To paraphrase a famous expression: Oppressed ones, heal thy selves. To argue is to acknowledge that the other side has some sort of claim to political, moral, and social legitimacy that must be respected in the name of civility and reason. For Douglass, that is an entirely false notion that he feels puts him in the position of almost having to apologize or express regret for challenging an obviously unjust system, for disturbing the public peace, as it were. Victims need no justification for their anger or their demands. I suspect this is the most influential part of Douglass’s speech for leftist audiences today. But, interestingly, Douglass does in fact argue his case as he furiously censures the nation’s intellectuals who would argue that Blacks are inferior and worthy only of slavery, the internal slave trade, the United States Congress for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and American Christian churches. His reasoning is impeccable. This is his “j’accuse” moment.

In thinking about the speech this year, I am struck less by his denunciation of slavery, powerful as it truly is, than I am by both the opening and closing of the speech. He begins by praising the American Revolution. It was an extraordinary achievement. He describes the Declaration of Independence as “the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it.” He goes on: “The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost”

(“Ring-bolt” and “chain” seem loaded and sardonic metaphors, coming from a former slave.) He notes that the rebels were “dangerous men,” who were taking considerable risks. (To be imprisoned by the British during the war in their filthy and deplorable jails was a brutal experience that killed many.) He likens them to the Hebrews taking on Pharoah. The rebels were on the side of “the oppressed against the oppressor.” He called the signers of the Declaration of Independence “brave men. They were great men too.” Douglass continues, “They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.”

“They were peace men,” Douglass said, “but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew it limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was ‘settled’ that was not right. With them, justice, liberty, and humanity were ‘final,’ not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men. They were great in their day and generation. Their solid manhood stands out the more as we contrast it with these degenerate times.”

The speech is clearly in the tradition of Independence Day orations: it is a jeremiad, about declension, about the descendants having fallen away from their ancestors, having betrayed their ancestors by failing to live up to their ancestors’ standards, by failing to fulfill their ancestors’ prophecy. The difference is that Douglass as a fugitive slave and abolitionist, as a Black man, can condemn the Whites of 1852 for being hypocrites, scoundrels, oppressors, and lacking the greatness of their forefathers while also justifying revolution, resistance on the part of the slaves, on the part of all Black people in America: After all, if the Founders were justified in their revolt, as they surely were, then why not Blacks whose oppression is so much worse than that experienced by the colonists in 1776? That is the subtext of this particular jeremiad.

It is not the case that Douglass has no use for the American Revolution or, in fact, does not identify with it. His is, shall we say, the detached, ironic patriotism that has always characterized how most Blacks feel about being Americans. “I do not like the way I am treated as a Black person in this country, but I like what the Whites achieved with their revolution. I like the idea of equality and the pursuit of happiness.” It is rather like Albert Murray’s point that Blacks liked what the White people had in America and what America itself was more than they liked what they had in Africa, even if they did not much like the Whites themselves.

About the war itself: Twenty thousand Blacks joined the British cause because the British promised freedom. Nine thousand Blacks were rebels, five thousand of whom were combat soldiers. Black people have blood equity on both sides. It was, for better or for worse, their war too. Douglass never makes this point. For the Black rebels, the United States of America was their country, in the end. That was a painful realization, as things turned out, but it was, to borrow James Baldwin’s term, “the scheme” we were in. There was little choice but to make the most of it and to believe in its possibilities more than the Whites did.

The ending of Douglass’s speech is even more curious. He defends the Constitution against the charge of being a document compromised by slavery, indeed, a document sanctioning it. “Fellow citizens! There is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? Or is it in the temple? It is neither. … if the Constitution were intended to be, by its framers and adopters, a slave-holding instrument, why neither slavery, slaveholding, nor slave can anywhere be found in it.” (italics mine)

His defense of the Constitution is part of his divorce from the Garrisonian branch of the abolitionist movement and its belief that the Constitution is an immoral compact with slavery. Douglass’s break with the Garrisonians is detailed in his 1855 version of his autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, a richer, more complex, and more compelling book than the more commonly read 1845 edition, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. (For instance, the account of his fight with the slave breaker Covey is different in My Bondage and My Freedom, where he describes being helped in the altercation by an enslaved Black woman, who is absent in the 1845 edition.)

But what is even more important is that with his praise of the Declaration of Independence in the beginning of his speech and his defense of the Constitution at the end, Douglass is, finally, saying that despite all else, he is an American, maybe not a happy one, maybe an estranged one. But he takes his stand on the two documents that made the country what it is. He is in “this scheme.” Just a few weeks after Independence Day, on July 24, 1974, Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, offering remarks before the House Judiciary Committee, said “My faith in the constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total.” What made this so striking, so memorable, was that a Black woman said it. Nearly everyone in the country that day was transfixed by her words and her dignity, by her belief in America. She was just echoing Frederick Douglass. Many of you may not quite realize that Independence Day for many Black folks is more important than you know, signifying the price paid for and memory of a paradoxical fate.