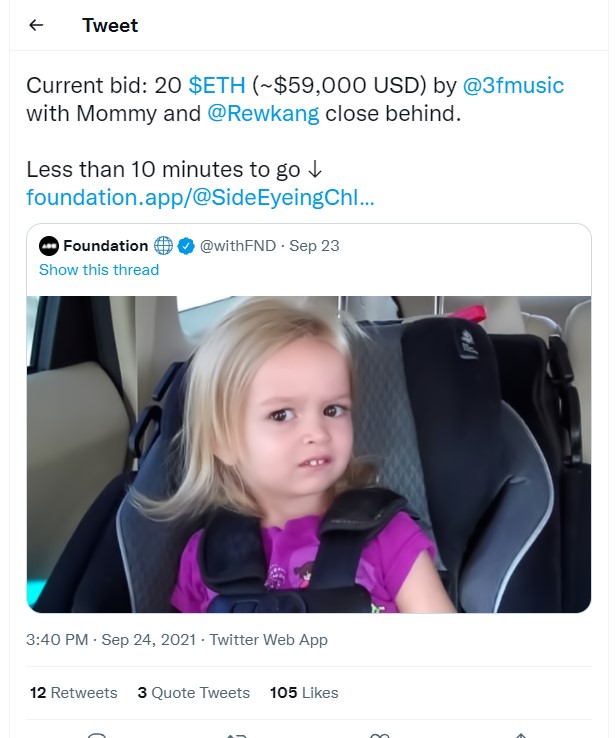

“Finally impressed?” asked the headline in The Washington Post. The NFT (non-fungible token) of the side-eyeing toddler meme had just fetched $74,000 in cryptocurrency.

“Nope,” I replied aloud, deleting the story.

We—need a word for United Statesians, because I do not want to drag Canada into this mess. We are the ones who, more than any other culture I know, persist in using money as a yardstick. After decrying materialism and tut-tutting over consumerism, we proceed to evaluate just about everything—people, companies, art, houses, restaurants—by their dollar figure, their salary or net worth, revenue or price. We love auctions because of that zingy validation when someone else wants what we want, not to mention the adrenaline rush of seeing who will win. And when a dramatic auction bids up the entirely subjective, crowd-sourced value of a snapshot, the media trumpet the ludicrous result.

The explosion of interest in NFTs seems a harmless quirk of the market, like the absurd price a retro action figure, boxed and pristine, can command on eBay. Interest is a measure of an artifact’s capacity to amuse us, and surely its clever owner should be rewarded?

Fine, sell the original for $74,000. But why would the mere fact of $74,000 wipe away skepticism and convince us, purely by the abstract value attached to the abstract cryptocurrency used to buy intangible pixels, that such barter holds promise for our future?

It may. But I would be far more impressed by an NFT that preserved craftsmanship before it was lost to the world. Or by a vast sum of cryptocurrency that managed to reach a disaster zone without being siphoned off by corrupt officials along the way.

Instead, it is the lighthearted capture of absurd sums of money that the media assumes (often accurately) will impress us. Sometimes those absurd sums reward the risk taken by early traders. Sometimes absurd sums shine a rainbow on a bubble that is about to burst. Rarely does an extreme price say much about real value.

Was a compressed photo of a Shiba Inu named Doge really worth the $4 million it commanded as an NFT? Was the Overly Attached Girlfriend meme worth $411,000? We assume from her wide-eyed delight that she has just read a fond text or email, and her expression carries so much giddy emotion that it is fun to use. In today’s market, that is often enough, just as the novelty and fresh beauty of tulips sent the Victorians over the edge.

Sarcasm turned to irony with the creation of an NFT that frames a New York Times column Kevin Roose wrote about the rise of NFTs. Up for auction as a prank, it sold in a bidding war for more $560,000. Again, harmless. The money went to charity. At the time, I grinned at the coup. But now I am having a hard time separating this recent nonsense from our society’s more grievous weirdness.

The way our government shuts down because we cannot agree how to spend scarce funds when need is abundant—and all the while, the wealthy and powerful who influence our policy are, instead of paying their fair share in taxes, sheltering their wealth offshore—or in South Dakota, for God’s sake. Meanwhile, we still insist on paying the bare minimum to the food-harvesters, kindergarten teachers, and garbage collectors who keep our society functioning, for example. Compare their salaries to those that reward athletes who play hard, celebrities who live out loud for our vicarious gratification, and executives whose work is a stressful, unending round of meetings and lunches. Upon them, we press sums of money so vast, they bear no relationship to a livelihood.

We assign dollar amounts based not on what something is worth, qualitatively, but on what we can get away paying or, at the other end of the spectrum, what we know will impress. Our economy rewards risk more than careful hard work, because everybody’s livelihood is based on the absurd, unsustainable, logically impossible premise of unlimited growth. For a while, that premise looked accurate—but only because we were plundering resources and stealing from the future. Formed in blithe confidence, our practices encourage waste, not thrift, and our stock market rewards short-term grabs for profit, not long-term wisdom.

In a “free” market, value is a function of buyers’ demand and a scarce supply, so businesses set the highest price the market will bear. That transactional strategy has zip to do with value. My grandmother’s star sapphire was once all the rage; now it is next to worthless, but the stone has not changed. GS Labs charges $380 for rapidly providing a $20 COVID test.

Capitalism and technology dance each other forward. Car radios are programmed to tell you what song is playing, which is so great—until a little ad enters that display box. They put in a speaker system at the gas station—how nice, music while I pump—but instead, it hawks stuff. Our courts even put a price tag on the loss of life or limb, as though money will undo the damage. I am not opposed to cash payment after a reckless accident injures someone or takes a loved one’s life. It is the equation, the attempt to count up what a particular life’s monetary equivalent might be, that troubles me. We have bought into (note the phrase) the twin notions that everything is a commodity and its price reveals its value.

In the end, it is all a giant game. And not a terribly impressive one.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.