What Elon Musk’s Baby Name Should Have Told Us

March 18, 2025

Elon Musk’s fourteenth child was born last month. The names of the previous thirteen are deliberately unusual words charged with personal significance for their papa.

The fourteenth’s name is Seldon Lycurgus.

Seldon, for Hari Seldon, a mathematician in Isaac Asimov’s science fiction Foundations series. First Minister of the Empire, he develops a new science, psychohistory, that predicts the future.

And Lycurgus? Does that name represent our future?

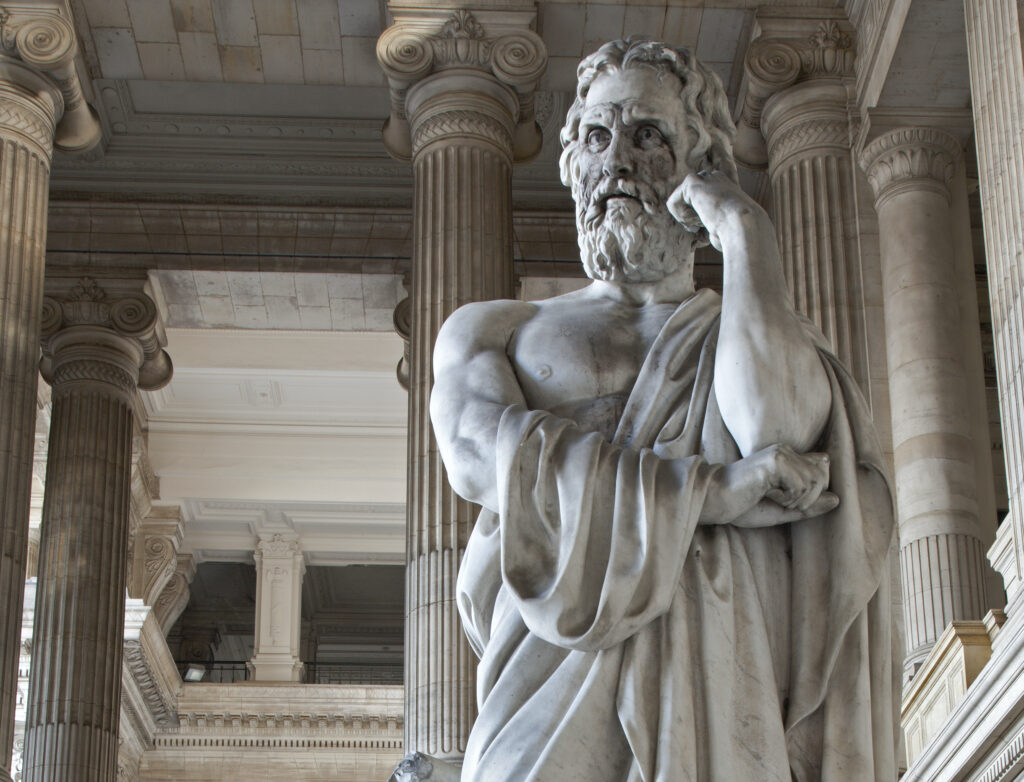

My historian husband blinks hard when he reads the birth announcement. Lycurgus, he tells me, forged the totalitarian system that governed the warrior city-state of Sparta in ancient Greece. Possibly real, possibly a mythic figure, he strove for order, efficiency, discipline, military prowess, and above all else, control. He therefore set up a rigidly stratified society whose only citizens were the Spartiates, the elite warriors at the top. Merchants and artisans were free but had no vote, and those in the vast bottom class, the Helots, became state-owned serfs forced to farm the Spartiates’ land—which had once been their own.

Helots were subject to constant surveillance, and they lived under the threat of periodic raids and state-sponsored terrorism.

Forget migration: unless foreigners had an approved reason to visit Sparta, they were barred from entry.

No need for tariffs, even: Spartiates were forbidden from engaging in trade.

Women’s primary responsibility was to birth and rear healthy children.

Male children, as future warriors, were preferred and privileged—as long as they survived the mandatory state physical. If they were not in excellent health, they were taken from their family and left at the base of Mount Taygetus to die.

Adult males lived in barracks and ate only with one another until they reached age sixty. Soldiers for life, they were guardians of the status quo that kept them on top and the Helots at the bottom.

Elon Musk is a technolibertarian, not an ancient Greek lawmaker. He is driven by reckless, sometimes adolescent ego and his own brand of idealism, not by a lust for warfare. But he values order, efficiency, discipline, and control as Lycurgus did. And to push freewheeling, unregulated tech into the future, he is more than ready to further weaken—or destroy—the institutions and customs that have stabilized us. He sees their constraints as unnecessary friction. So it makes sense that he would choose Lycurgus, rather than, say, the traditional American favorite Cincinnatus, who relinquished power as soon as the crisis passed.

Still, it is interesting that the wealthiest man in the world would be drawn to a leader who despised accumulated wealth, banned luxury goods, and switched the coin of the realm to plain, dull iron. There is something Spartan about Musk, though. He has the asceticism of a teenage boy who wears black T-shirts and holes up with his computer for hours on end. And he trusts guys like himself.

When he gave a handful of men ages nineteen to twenty-four access to sensitive government data, he pronounced them his “young Spartans.” Krepteia would have been more accurate. That was the Spartan secret corps charged with terrifying the Helots to encourage hard work and discourage any form of resistance.

To reassure those shocked by this handover to six guys with scant experience, Musk posted on X, “Not many Spartans are needed to win battles.” My husband lifts an eyebrow: “Obviously he never heard of the crushing Spartan defeat at Leuctra.”

Seldon, the baby’s first name, also carries a charge. Seldon’s superpower was prophecy, and after predicting the fall of the empire, he established a Foundation to accelerate the arrival of a new empire. The scientists and scholars of The Foundation take shelter on a remote planet, you know, like Mars. The Foundation must then navigate The Seldon Crisis, a period of predicted chaos.

Well, chaos has arrived. Now I wonder if Asimov could have imagined anything as dystopian as a Spartan United States. The plot is dubious, a tangle of contradictions: Populists grow wary of immigrants and impatient with academic and scientific experts, vote to make their country Christian, and find themselves subject to the whims of an immigrant intellectual whose god is technology. And whose hero who would have turned many of them into Helots.

Irony on a platter. Yet the media, scrambling to keep up with Musk’s rapidfire dictates, never once stopped to ponder the historical and cultural contexts of the two names he chose. The rush of new-baby coverage was all about eccentric Elon, his progeny and personal branding.

Maybe reporters took the choice at face value. Musk has said that he admires Lycurgus’s wisdom, strength, and ability to rise above revenge and forgive. When he proposed radical laws that would transform Sparta into a militarized state, a few citizens were still capable of resistance, and one was so enraged, he punched Lycurgus in the eye. Instead of hitting back, Lycurgus invited the man to his home for dinner and won his support.

Calling this an act of empathy, Musk bestowed a name of high praise. He pronounced Lycurgus a BAMF, badass motherfucker. The Helots might agree—but with fear and resentment, not admiration. As usual, the appraisal depends on where you stand.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.