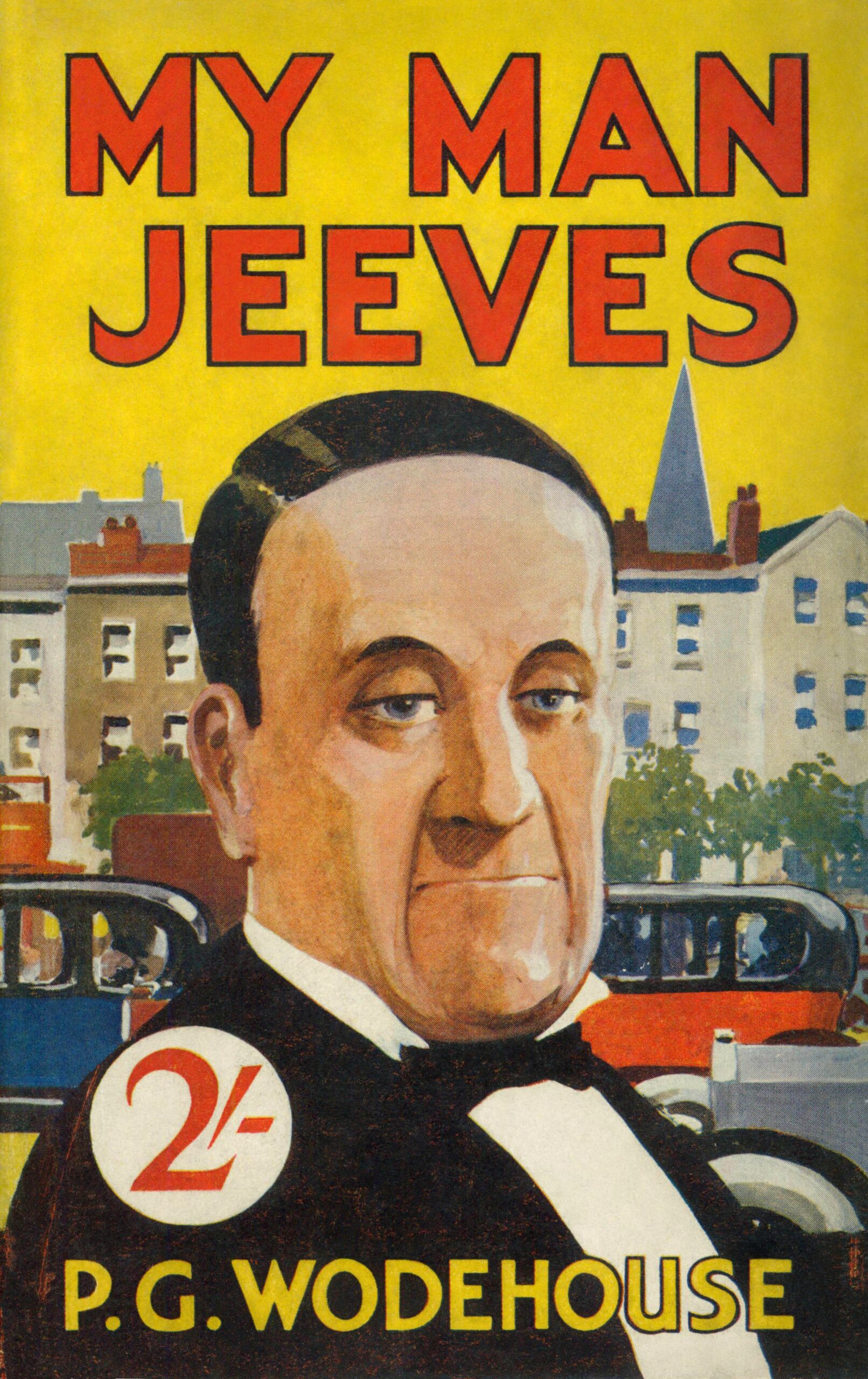

(Wikimedia Commons)

Douglas Adams called him “the greatest comic writer ever.” Hilaire Belloc went so far as to pronounce him “the best living writer of English,” and rather than retract that excessive praise he explained it. P.G. Wodehouse had perfectly accomplished what he set out to do: create and sustain a world that would amuse us.

What really tore it for me, though—after managing to avoid reading Wodehouse for half a century—was learning that the fiercely witty Christopher Hitchens held him in the highest esteem. Incidentally, both Hitchens and Salman Rushdie thought Wodehouse, that silly, fluffy, whimsical writer, had written the consummate anti-Nazi diatribe:

The trouble with you, Spode, is that just because you have succeeded in inducing a handful of half-wits to disfigure the London scene by going about in black shorts, you think you’re someone. You hear them shouting, ‘Heil, Spode!’ and you imagine it is the Voice of the People. That is where you make your bloomer. What the Voice of the People is saying is: ‘Look at that frightful ass Spode swanking about in footer bags! Did you ever in your puff see such a perfect perisher?’

Dated, you say? Edwardian prose that no longer holds up? Neil Gaiman would disagree. David Foster Wallace called Wodehouse “timelessly funny.” For Stephen Fry, “he exhausts superlatives.” John le Carré insisted that no library “is complete without its well-thumbed copy of Right Ho, Jeeves.”

Which makes me wonder: did they love his silliness or his complexity?

Wodehouse was shy, socially awkward, and reclusive, yet he wrote endlessly of Bertie Wooster’s boisterous hijinks and romantic escapades. Wodehouse lived through two world wars, yet he wrote of serene villages and joyous young folk. He spent his adult life in the States, yet he set every tale in England. He had an Edwardian mistrust of intellectuals, yet his work delighted them.

P.G. Wodehouse (pronounced Woodhouse, just to add a wrinkle) was one of a type I used to despise and now grudgingly admire: those who maintain their equilibrium by refusing to look at anything dark or glum. Sturdy as a hard rubber ball, he bounced along in near-total denial. He wrote Joy in the Morning while interned by the Germans during World War II and set it “in the midst of smiling fields and leafy woods, hard by a willow-fringed river, and you couldn’t have thrown a brick in it without hitting a honeysuckle-covered cottage or beaning and apple-cheeked villager.”

His need for escape dates well before the war, and it is easy to psychoanalyze. When he was two years old, his mother rented a house in Bath for him, his brothers, and a formidable governess, then returned to her husband in Hong Kong. From then on, the boys were passed among various aunts and uncles. Plum (the toddler slurring of Pelham Grenville stuck) barely saw his mother until he was fifteen. “I met her as virtually a stranger and it was not easy to establish a cordial relationship,” he would write later. Also: “Looking back, it was an odd life with no home to go to, but I have always accepted everything that happens to me in a philosophical spirit; and I can’t remember ever having been unhappy in those days.”

Why do I appreciate his denial? Because for a small boy with no recourse, it feels brave and resourceful. Because the rest of us might have gone a little too far in our wallowing. And because his resolute cheer allowed him to be kind. He adored his wife and his stepdaughter (signing letters to her “Cheerio, old cake/Oceans of love/Your Plummie”); he cherished his best friend and indulged his canine menagerie. Self-deprecating, he succumbed to no rivalries and took no shots—except at the entire British class system, and there he was clear-eyed but still fond. Reading him, you can enjoy the foibles of human nature again. No one need lie on a couch; no one is excoriated, reviled, or canceled. The quirkiest eccentrics and most exasperating dowagers are an accepted part of the landscape, fun to foil but never truly hated.

Was he just naïve? He avoided mention of sex. There was a schoolboy innocence about him, as though part of him were still at Dulwich, the boarding school where he first felt the reassurance of belonging. He kept that Edwardian ease, feeling no need to be Relevant or Socially Engaged or Make a Difference with his writing. His plots were gentle and slight, returning an innocence that two world wars had destroyed. His own wartime experience might have made the past even more appealing: after he was interned by the Germans, he set himself up for disaster by agreeing to a series of humorous broadcasts he thought would be aired only in the States. The Germans used those broadcasts for propaganda, and he was described on the BBC as “a rich man trying to make his last and greatest sale—that of his own country.”

Was he just naïve? He avoided mention of sex. There was a schoolboy innocence about him, as though part of him were still at Dulwich, the boarding school where he first felt the reassurance of belonging. He kept that Edwardian ease, feeling no need to be Relevant or Socially Engaged or Make a Difference with his writing. His plots were gentle and slight, returning an innocence that two world wars had destroyed. His own wartime experience might have made the past even more appealing: after he was interned by the Germans, he set himself up for disaster by agreeing to a series of humorous broadcasts he thought would be aired only in the States. The Germans used those broadcasts for propaganda, and he was described on the BBC as “a rich man trying to make his last and greatest sale—that of his own country.”

A bit over the top, that. “I am a fool, but I am not a renegade,” he is reported as saying. I imagine a clipped tone, a mustered dignity rare in a man so deliberately lighthearted. Stung by the vilification, he made the United States his lifelong home. Readers rarely guessed he was writing from Long Island and not a village that resembled Steeple Bumpleigh.

“If only those blighters would realise that I started writing about Bertie Wooster and comic earls because I was in America and couldn’t write American stories,” he told a friend, “and the only English characters the American public would read about were exaggerated dudes.”

He was astute. “Reluctant though one may be to admit it, the entire British aristocracy is seamed and honeycombed with immorality,” he once remarked. He let his quips come right to the edge of cynicism: “Slice him where you like, a hellhound is always a hellhound.” A few more of these offhand jabs, and one suspects rather less naivete than he presented.

“Was the ‘Plum’ Wodehouse we thought we knew—the pipe-smoking, Peke-loving chap exclusively inhabiting some private and personal universe he carried around in his head—perhaps his own finest creation?” ask the authors of P.G. Wodehouse: In His Own Words. “Was the divine dottiness, this amiable otherworldliness the perfect protection used by a man shrewd enough in the ways of the world to realise that it was the perfect way to ensure the privacy he craved?”

If so, it worked. Once famous, he took shelter in his boyhood shyness. “Cornered at one of these affairs by some dazzling creature who looks brightly at me, expecting a stream of good things from my lips, I am apt to talk guardedly about the weather,” he admitted, adding that he usually wound up “left on one leg in a secluded corner of the room in the grip of that disagreeable feeling that nobody loves me.” The feeling was not new. “Even at the age of ten I was a social bust, contributing little or nothing to the feast of reason or the flow of soul”—a phrase Hitchens made his own and used regularly—“beyond shuffling my feet and kicking the leg of the chair into which loving hands had dumped me.” That sentence breaks my heart, not for the shyness but for the retrospective insistence on “loving hands.” The hands would have belonged to one of his aunts—and gave no guarantee of affection.

Sophie Ratcliffe, professor of literature and creative criticism at Oxford, edited a collection of Wodehouse’s letters, and her commentary is sensitive. To praise his wife, Ratcliffe points out, he praised her outfits, not her eyes or soft lips; to write of emotions, he attached them to objects (“a moody forkful” of eggs or “a thoughtful lump of sugar”). The nadir of his melancholy, channeled through Bertie Wooster, was the arch comment, “It would be deceiving my public to say that I was feeling boomps-a-daisy.”

How tempting it would have been to grill the man, poke beneath that unrufflable surface. He resisted all questions about his private life and his innermost thoughts and feelings, seeing them as intrusive.

Ah, but now he is dead. We can observe his nature as closely as he did ours, the proof laced through every book.

When an aristocrat was informed by the all-knowing butler Jeeves, “Your Lordship has inadvertently put a fork in your coat-pocket,” Wodehouse described how the aristocrat fumbled in his pocket “and, with the air of an inexpert conjurer whose trick has succeeded contrary to his expectations, produced a silver-plated fork.” Writing of a young man on a hotel terrace in Cannes, he noticed that “a look of furtive shame, the shifty, hangdog look which announces that an Englishman is about to talk French.” Of Bertie, he wrote, “It would be paltering with the truth to say that he likes babies. They give him, he says, a sort of grey feeling. He resents their cold stare and the supercilious and up-stage way in which they dribble out of the corner of their mouths on seeing him.” Even dogs, he studied: “It would seem that a dog has to be small to be fond of a joke. You never find an Irish wolfhound trying to be a stand-up comic.”

Wodehouse’s inimitable style was as hard to analyze as his emotions; one critic described the task as “taking a spade to a soufflé.” The wordplay was truly playful—in Bernard Levin’s phrase, “a wit which comes out of the shape of the sentence.” Someone was “as broke as the Ten Commandments.” Jeeves “moves from point to point with as little uproar as a jelly-fish.” “She uttered a sound rather like an elephant taking its foot out of a mud hole in a Burmese teak forest.” There came “a sort of gulpy, gurgly, plobby, squishy, wofflesome sound, like a thousand eager men drinking soup in a foreign restaurant.”

All those wonderful words, yet the pacing stayed tight and fast. He kept his brain sharp, too, reading through all of Shakespeare every year. P.G. Wodehouse stayed on life’s surface because he preferred the sparkle of sunlight, not because he was unable to swim.

• • •

The man wrote more than seventy novels and three hundred short stories and five hundred essays and articles, plus light verse, sixteen plays, and lyrics for twenty-three musical comedies. He worked with Cole Porter on Anything Goes and collaborated frequently with Jerome Kern, most notably by writing the lyrics for “Bill” in Show Boat. Through it all, he never pretended to be anything but Edwardian: “My stuff has been out of date since 1914 and nobody has seemed to mind,” he remarked. But was it out of date? The dialogue might be outmoded slang, the settings and customs quaint, but the world he created remains, in the words of Kingsley Amis, “unmarked by the passage of time.”

“It is a world that cannot become dated,” Evelyn Waugh pointed out, “because it has never existed.”

Escape is often necessary.

“I sometimes wish I wrote that powerful stuff the reviewers like so much,” Wodehouse once admitted, “all about incest and homosexualism.” His way of writing a novel was “making the thing a sort of musical comedy without music, and ignoring real life altogether.” That would have appealed, after two world wars—and it appeals again, today.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.