Demons seem to be making a comeback.

The Catholic church kept mum about its exorcisms for decades. A hush used to fall in my own family; my grandparents knew one of the strong young Jesuits who had been called upon to assist (mainly by holding the boy down) at the rites that inspired The Exorcist. Father Bowdern’s name was always spoken in lowered tones, with rueful head shakes implying that the ordeal had broken him. My Jesuit uncle refused to repeat the stories he surely heard. Older Jesuits smoothly dodged my questions, wary of encouraging spooky nonsense about the supernatural.

Now Pope Francis speaks freely about the demonic. He urges priests to refer troubled parishioners for exorcism whenever they deem it necessary. He sees “the work of the devil” in division within the church, stresses on the family, and such daily temptations as gossip. “Maybe his greatest achievement in these times,” Francis writes, “has been to make us believe that he does not exist.”

If so, Satan is slipping. Evangelical Christians are exorcising, too. We regularly refer to mass shooters as evil or demonic. Demonic horror is its own film genre. Trumpers have spotted “a satanic portal above the White House,” which they identify as “demonic territory.”

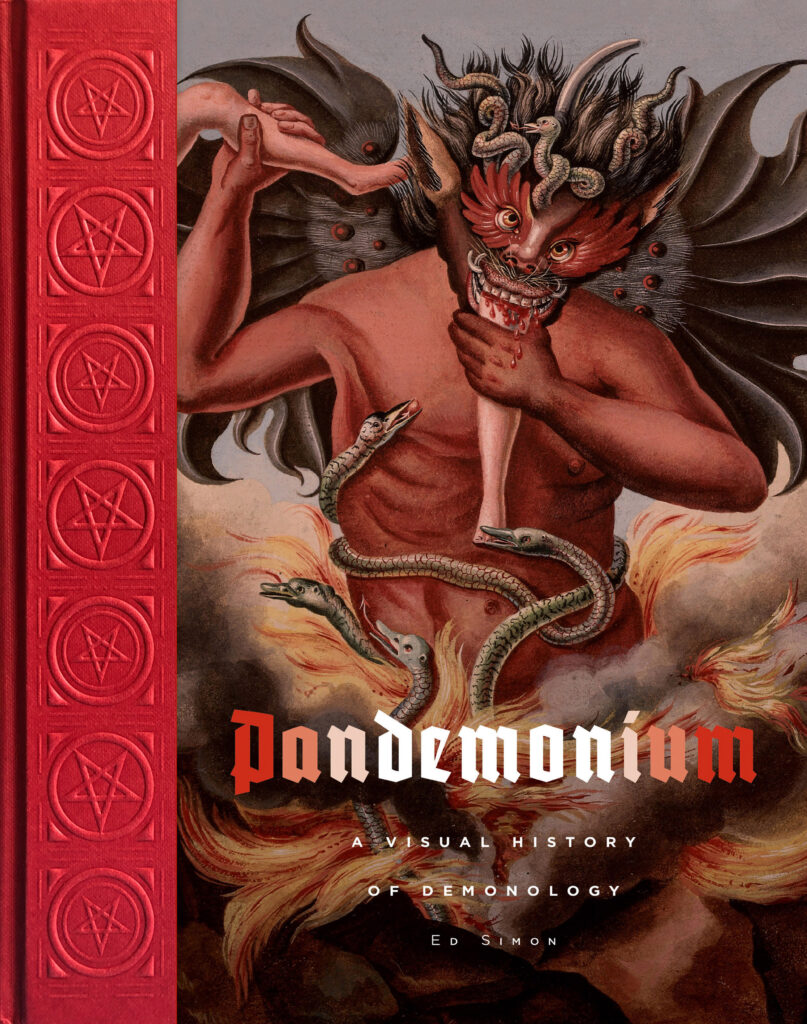

What is a demon, anyway? Paging through Pandemonium—the first comprehensive popular history of demonology and, with its gorgeously horrific illustrations, a coffee-table book for the brave—you can trace centuries of shapeshifting. First a satyr or hellmouth, then a horned hooved split-tailed villain silly enough for vaudeville, then a slyly handsome dark angel, and then the feathers morph into bat wings….

The word comes from the Greek daimōn, a “supernatural being” or “spirit.” In early use, it could be a positive, a spirit influencing one’s character for the better. That meaning lasted, taking on the sense of muse or genius. But “demon” gathered energy in its malevolent sense, naming some force outside us that tempts us away from God or our best self.

In modernity, that external force crawled into our skull; we speak of inner demons, including addictions, compulsions, and voices of doom or self-mockery. The shift is not as dramatic as it seems: in the second century, Clement of Alexandria was already noting how easily we can be possessed by our own appetites. But it is more fun to blame a demon (or a tray of pastry, or a bottle of Scotch) than to examine what made us vulnerable to temptation in the first place.

In the “Daemonologie” King James wrote before tackling the Bible, he described demons of obsession, following certain people to outwardly trouble them at certain times of day, and demons of possession, entering the person to trouble them from within. Buddha was tempted by the demons Rati (desire), Raga (pleasure), and Tanha (restlessness). In medieval Europe, a demon was assigned to each of the seven deadly sins. Lucifer, the fallen angel, tempted us with pride; Beelzebub with envy, Satan with wrath, Mammon with greed, and so forth.

Demons dance back and forth between our world and the netherworld. But they are also psychological intermediaries, stand-ins for our problems. With a demon as our nemesis, even an inner battle can take place outside us. Satan can be wrestled in the desert (arid wastelands being a demon’s natural habitat). The offending bottle can be poured down the drain.

Banish every inner demon, and demons will still have a job, because we also use them to explain the inexplicable. A poet, mystified by the words pouring through him without conscious intent, humbly credits his daimōn. A pope watches the nuclear family that was meant to hold the world together crack and shatter and blames the devil. We watch acts so cruel and aberrant, we have no word except “demonic.”

The experienced, matter-of-fact police officer who found two little boys and their mother strangled said what he sensed was “evil. There was a presence of evil in that house.” Was there, really, though? As it turned out, the boys’ father had strangled them. He had a warped arrogance, a child’s selfishness, and a simple and rigid mind; he was hardly a sexy Mephistopheles. We reach for words like “evil” and “demonic” when we are overwhelmed, unable to process the horror. The police officer shook off that chill and solved the crime, but too often, pronouncing some act “demonic” removes it from the human realm—and stops us from seeking solutions.

It always has. This cross-cultural array of spirits, false idols, muses, obsessions, wicked humans, fallen angels, and hybrid human-beasts has dwelt among us for millennia. Paganism was crowded with lesser demons thwarting or tugging at the human will. Then the Jews settled on a single god, and the problem of theodicy was born. How do you reconcile an all-powerful, all-loving Creator with an obviously broken world filled with suffering? There had to be another singular force, one almost as powerful as God, yanking us in the opposite direction.

And so, little by little, the Old Testament’s demons and ha-satan, legal prosecutors, merged into a single demon, a capitalized Satan borrowed from the Zoroastrians and eventually explained as the chief of the fallen angels. The rabbis did not dwell on Satan, but the early Christians obsessed, giving him a backstory as a fallen angel himself. “Like a crack running down through reality itself,” writes Pandemonium author Ed Simon, “the insurrection of the rebel angels against God’s sovereignty is supposed to explain the malignancy of our existence, the warped nature of our being.”

The explanation never quite held, and we tried to cast it aside. But now? Andrew Delbanco sums up our dilemma in The Death of Satan: “A gulf has opened up in our culture between the visibility of evil and the intellectual resources available for coping with it.” Confronted by forces we do not understand and cruelty we cannot absorb, we are again—whether we are religious or not—using the vocabulary of the demonic. It takes various forms: a forked-tail caricature used to scare fools; a coolly strategic demonization of political opponents; a raw attempt to express the magnitude of an act and our helplessness in its wake.

The little red guy seems too impish for such big jobs. We need the sort of Satan you find in the Qu’ran, an entity made of fire. Because no matter how we define them or where we situate them, our demons can consume us.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.