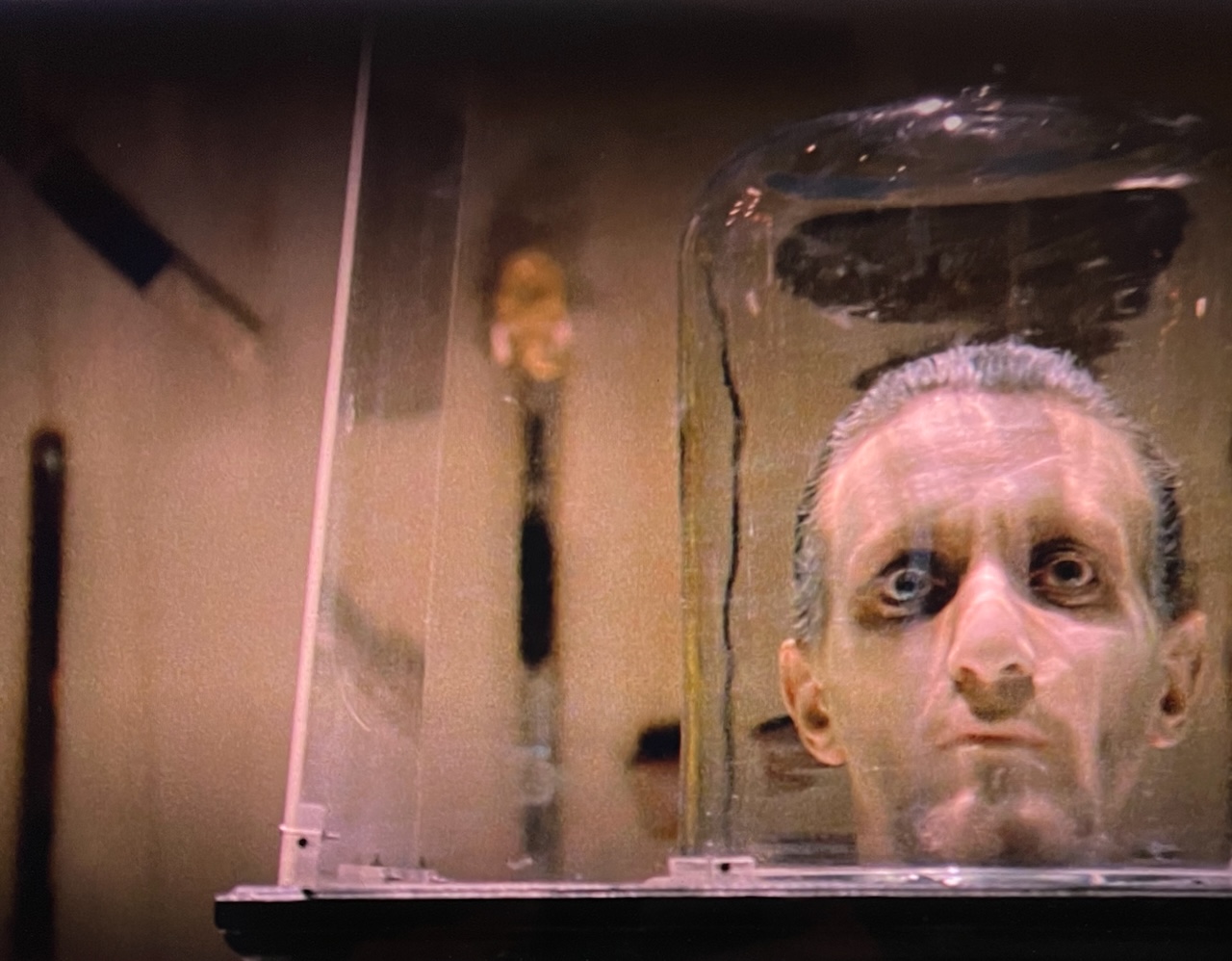

False Dmitry II: A still from the Soviet film Zerograd, directed by Karen Shakhnazarov

It is not always what we might call “fun” to go new places, talk to people, and experience things to try to understand who they are. Sometimes you get a museum with a good gift shop; sometimes you get The Wicker Man.

We might call this “educational” instead, but more often than not the mystery is only deepened. This month I have been visiting a town where historical labor-radicalism and right-wing contemporaneity lie together as quietly as the grave. What am I seeing?, I have wondered as the names, dates, events, and sensory impressions pile up.

By coincidence I found the film Zerograd this week, the Soviet entry for Best Foreign Language Film for the Academy Awards in 1989. Amazon describes it this way: “Part Kafka, part Agatha Christie and part Monty Python, Russian director Karen Shakhnazarov’s surreal satire of Communism follows an Everyman engineer named Varakin (Leonid Filatov) who arrives in a remote city where nothing quite makes sense, but everyone acts as if it does. And once he arrives in Zerograd, he finds himself unable to escape.”

In his desperate search to find transport back to Moscow, Varakin is talked into visiting a local museum in an abandoned mine. His guide, speaking flatly, explains the history of the place as they walk through the exhibits. The mannequins in the tableaus are played by real people oiled to look plastic, and their eyes are disturbingly alive.

The docent’s patter sounds like this:

“They used to mine coal here in the 19th century. They came across an ancient burial site while sinking the shaft. Butov, a merchant and great archaeology lover, bought up all the land in the area. He kept on digging and that’s how the museum came to be. […] This sarcophagus contains the remains of the Trojan king Dardanus.”

“Wait, how did the Trojans get here?” Varakin says.

“Professor Rotenberg has irrefutably proved that after Troy fell some of the Trojans went north, and having reached this area, they founded the first settlement here,” says the docent. As proof, “Here’s an inscription: ‘Dardanus, son of Helenus, grandson of Priam.’ The same inscription is on the shield found by Butov beside the sarcophagus. Let’s go on.”

A poster on the wall shows a dove being released, the caption proclaiming in Russian, “The source of our strength lies in historic truths.”

The docent indicates a different exhibit. “The 2nd cohort of the 14th double legion of Mars. […] Titus Rubrius the legion commander reported to Nero on their disappearance without a trace while enroute from Britain to the Caucasus. The cohort’s remains were discovered by Butov while they were digging the second shaft.”

Varakin protests, if only to hang on to his sanity. “Nonsense,” he says, “the Romans never reached Soviet territory.”

“These sculptural portraits were restored by our artist Ryumin using the Gerasimov method,” the docent replies.

He points. “The bed of Attila on which the leader of the Huns violated the queen of the Visigoths, in front of his horde. Professor Rotenberg found traces of semen on it, from which he derived a genetic fingerprint. He then fed the data into a computer, resulting in a perfect likeness of Attila.” The head in the box looks like F. Murray Abraham’s.

“The first rock ’n’ roll performers in town,” he says, moving on, because all the exhibits are equally important to the place. “Nicolai Smorodinov, Secretary of the town’s Young Communist League, who had them expelled.”

Without pause: “The pistol with which Peter Urusov shot False Dmitry II. And here’s the imposter’s head.”

Varakin cannot help but be curious, which is how the universe pulls us in. “How on earth did the head get here?”

“When False Dmitry was killed, Marina Mniszech ordered her doctor Ismael to embalm her husband’s head. Marina Mniszech’s lover Ataman Zarutsky lost the head at cards to a Pole, Uhlan Beletsky, who was killed during Minin and Pozharsky’s siege of the Kremlin, and the head went to Fyodor Kuzmin, a soldier from our town. But he’s not here. Let’s go on….

“Here you see the Kievan Prince Vladimir when he took the heroic decision to convert Russia to Christianity. The famous revolutionary Petrov, born here in town, a member of the ‘Black Repartition’ group, was betrayed to the Tsarist secret police by the head of the combatant Socialist Revolutionaries, the agent provocateur Azef—here he is. Petrov died in jail. And here’s Azef’s mistress, Lady N, an actress in a cafe chantant. Here’s Friar Julian, ambassador and spy in Russia for Hungarian king Bela IV. This is Burtsev, another representative of our town, superintendent of the Florence Hotel in Moscow. In 1918 the anarchists held a conference there. This is Burtsev. Here he is entering with a pillow. Ataman Makhno himself took part in the conference. Here he is talking with the commander of the Jewish Army battery, Abraham Schneider. To his left is Gavriusha, the famous commander of Makhno’s Black Hundred, who said he would hack down his own mother and father if Makhno only ordered it.

“Our town’s first Stakhanovite hero, Yegor Bykov.”

The scene goes on another eight minutes.

This mimics my experience taking a college survey on 2,000 years of Russian history. But it is also a good metaphor for how we become conscious that we know practically nothing, as the ancients said.

I got curious about Zerograd’s director, Karen Shakhnazarov, and learned that despite his satire of communism, Russian history, and bureaucracy, and despite being the Chairman of Mosfilm, one of Russia’s most venerable film production companies, celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, he publicly supported Putin’s taking of power, his annexation of Crimea, and his invasion of Ukraine. He apparently has made hyperbolic statements on Russia-1, the flagship of state television, about those he believes are Nazis now.

The descent into the coal mine is a good metaphor for how we dig down in the past to understand but find that it is perilous, a place that can crush, bury, and smother with its details, a place where the bedrock still burns.