A sloth’s digestive system can work for almost two months to break down a single trumpet-tree leaf.

• • •

Leonardo da Vinci learned at race speed, gulping down physics, arithmetic, philosophy, astronomy, anatomy, medicine, literature, languages, and art history as though someone were holding a stopwatch. Self-taught, he cheerfully admitted mistakes and started over. His bursts of enthusiasm had him not only inventing and painting but playing the lyre; working as a chef at The Three Snails; building theatrical machines; planning parties amid jungles of fairies, with servers dressed as giant birds; planning a wedding feast with a sixty-meter cake (rodents interrupted that one).

• • •

Digestion’s residue need only leave the sloth’s elongated, pear-shaped body once a week—which is lucky, because the sloth is vulnerable on the ground. After that hurried (in sloth time) trip to the loo, the sloth spends the rest of the week just hanging out in the tree canopy, where it is safe.

• • •

Da Vinci thought of the sea as the Earth’s lifeblood, water as the pulse of nature. He filled a leather bag with air so it could act as a life preserver; sketched what today we call a submarine; engineered a paddleboat; then designed a leather diving suit and breathing apparatus that could take someone deep into the sea. In the current exhibition at the Saint Louis Science Center, the reproduced suit is white, and it looks alien—as it would have looked to da Vinci’s friends in the Renaissance, no matter what color it was.

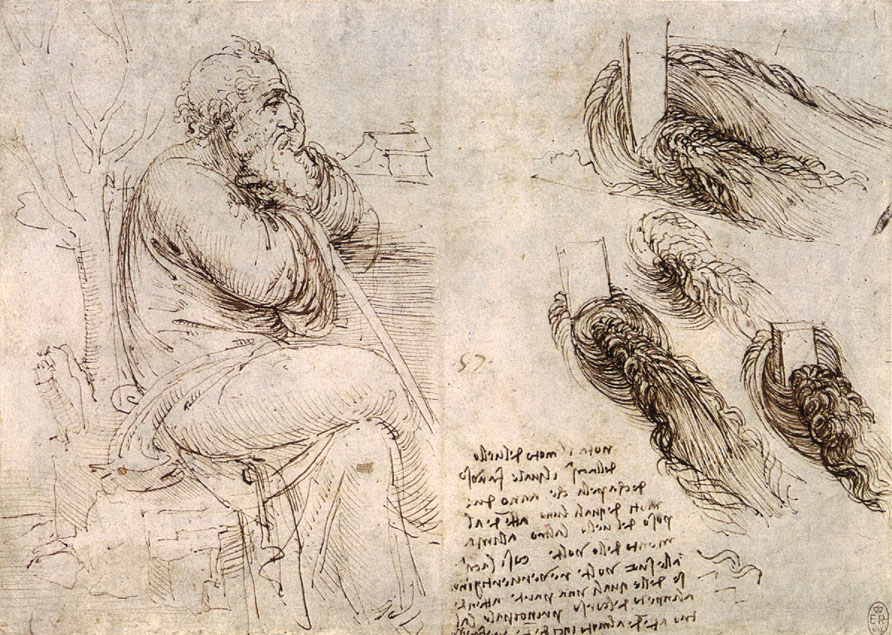

Leonardo da Vinci’s “Old Man With Water Studies,” circa 1513, thought be to an early self-portrait.

Even more fascinated with flight, he endowed the angel in an Annunciation series with meticulously accurate bird’s wings, invented an ornithopter with flapping wings, modeled another wing after a bat’s wing, and firmly believed that a man flapping big paddle wings could take off and soar at any moment.

• • •

Sloths spend six months nursing, then hang onto Mom for as long as two years. At the St. Louis Aquarium, Coconut, who is eleven months old, has quite a few surrogate mothers, and like any good matriarch, they urge her to eat. She is small for a sloth her age, only two and a half pounds. She sleeps, as do all her kind, about twenty hours a day. Aquarium staffers want her to get used to her big-girl cubby soon, but for now, they carry her around in a baby blanket, and whenever possible, they wear her, cradling her in a soft sling as they do quiet tasks.

• • •

Da Vinci was born on the wrong side of the blanket, the child of a wealthy legal notary and a sixteen-year-old orphan who was quickly married off to a farmer in Anchiano, a tiny town near Vinci. His father welcomed him as a son and reared him on his estate, where Leonardo learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Still, he clearly felt the difference, and he called himself “unlettered.” In 1467 he became an apprentice, eager to learn painting and sculpture and the technical skills that made certain effects possible.

• • •

Sloths can easily get overstimulated. They vary in temperament, but some are sensitive, recoiling from loud bustling activity or crowds.

• • •

Fussing about varnishes, Da Vinci thoroughly exasperated Pope Leo X, who said, “Alas! This man will never do anything, for he begins by thinking about the end before the beginning of his work!” Famous for procrastinating and then leaving projects unfinished, da Vinci may well have had ADHD. Easily bored, he had a restless creativity that tempted him to switch from one thing to the next rather than focus and finish. But that fluidity and impulsivity let him try things without hesitation, diving into any subject or possibility that intrigued him. “Nothing can be loved or hated,” he wrote, “unless it is first understood.”

• • •

Though they avoid the ground (except for that once-a-week bathroom break) sloths love a bit of controlled sensory stimulation. When an aquarium staffer brings new straw, the older sloth will hang down from a branch, stretched out like pulled taffy, so she can grab a bit of straw and lift it to her nose to breathe in the scent. In the South American rainforest, this vertical stretch is what allows rain to drip off a sloth’s coat, a mix of tan and dark brown that looks bristly, like a coconut fiber doormat, but is actually thick and cashmere soft.

• • •

Just a few epiphanies made it possible for DaVinci to turn his genius in a hundred different directions. Almost two centuries before Newton formulated his laws of physics, da Vinci had realized that certain basic laws carried through the human body, all other aspects of nature, and even machines. He had also realized that math was at the core of these laws. When he illustrated De Divina Proportione in 1498, he already had a sense of its subject: the golden ratio’s use in art and architecture. (Divide a line into two parts. If you have created a golden ratio, then you will get the same answer, about 1.618, if you divide the entire line by its long part and if you divide the long part by the short part.) The elegance of this ratio’s proportion pleases to the eye, perhaps even the soul, for reasons known only to people who understand how math can be beautiful. Artists just know how to use the golden ratio, as da Vinci did in the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, Vitruvian Man, The Annunciation … (Dan Brown also used it in The Da Vinci Code, but we will leave that be.)

• • •

Coconut’s system is very sensitive. Sloths need a particular temperature to digest their food, and they do not regulate their own body temperature the way we do. They cannot even shiver. They have to count on their surroundings to make it possible for them to thrive. This is why a sloth move so slowly: She must conserve energy, lest a slight change in conditions prevent her body from absorbing nourishment. “So Coconut’s a high maintenance broad, is what you’re saying,” a guest at the aquarium teases.

• • •

Whether because he struggled with handwriting as a boy or because he was secretive, da Vinci wrote backwards, and when he designed a war carriage with scythes on the wheels, the Italian government misread the mirror writing and attached the horses’ reins the wrong way. Where he communicated most clearly was in his sketches and painting. Sfumato, a smoky technique of creating depth, and chiaroscuro, based on his study of light, added dimension and realism.

• • •

Sloths are solitary by nature, but they do seem capable of bonding. Held close, Coconut keeps arching her neck and leaning back, her pointy brown nose straight up and her beady brown eyes focused on the curator, listening to her talk.

• • •

In nearly seven thousand pages of jottings, da Vinci revealed next to nothing about himself—his emotions, his hopes, the thoughts that kept him up nights, the dreams that pushed him forward. We do know that just before his twenty-fourth birthday, he was arrested for sodomy. The charges were later dismissed for lack of evidence, but as a review of Walter Isaacson’s biography points out, the time in prison may have inspired sketches he made soon after: one of “a machine that he explained was meant ‘to open a prison from the inside,’ and another for tearing bars off windows.”

We also know that he was handsome enough to stop your heart, scented his hands with lavender and dressed in silks and velvets, moved with grace, was probably gay, often celibate, fascinated by androgyny, and as inscrutable as his Mona Lisa.

• • •

Sloths do not show a wide range of behavior, because they have such little energy to expend. “Nope, I did two things today, I’m done,” says a curator, voicing Coconut. We tend to equate slowness with a dull mind, but these guys are smarter than we think, and can reliably understand what a human wants of them. You just need enough patience to wait while they take the time they need to comply.

• • •

The French King gave Leonardo the title of First Painter, Architect, and Mechanic of the King, but set no quotas, so da Vinci spent most of his time on his scientific studies. Now that we can examine his codices, or notebooks, we see from the 6,500 pages of notes and drawings (and those are only the ones he kept, after age thirty-five, and half of the pages were lost) that science was his deepest love. He used it first to serve his art, studying anatomy and the nature of light, and then he used his art to sketch and develop his scientific ideas.

• • •

We have a newfound affection for sloths (just check your phone’s emojis and gifs). They represent the unruffled, placid ease we cannot seem to attain for ourselves. As a result, they are in high demand as pets—which is problematic, because they do not breed well under such circumstances. More and more sloths are being taken out of the wild to feed our demand for cuddling they tolerate but may not even enjoy. Soon their population will dwindle, and we will have nothing left to remind us that we have forgotten how to live.

• • •

From da Vinci, we have dozens of artistic masterpieces; the first parachute, its linen sealed airtight; the aerial screw that was later developed into a helicopter propeller; a winged flying machine that became the airplane; a self-propelled cart that became the car; a barreled cannon that became the automatic weapon; underwater diving equipment; machines to measure wind speed and humidity, weighing cotton that has soaked up the water carried by the air; ball bearings to reduce friction between moving objects; spiral springs that accumulate the kind of energy that sends a Slinky down the stairs; war machines and movable bridges he crafted to support his painting; the robotic knight, early automation; the model for an ideal city; an armored tank that looks a bit like a spaceship …

• • •

This would be a cruel comparison, a slam at the underachiever cursed by biology to conserve her energy rather than throwing it into the world in a brilliant show of pyrotechnics … except that people watch the little sloth with such tender expressions. How lovely it would feel, one woman murmurs, to just cling to a warm friend all day, spread-eagled against their tummy. Children beg to pet Coconut (no dice) and grownups soften their voices to talk to her. Coconut will never make anybody feel like a slacker. She will never be held up, like a hated cousin or a Renaissance wunderkind, as proof of our inadequacy. Coconut just is. And in fully living her particular destiny, her sloth-nature, she comes as close to what the Buddhists call enlightenment as da Vinci did.

Though it would be hard to call her “awakened.”