The Senate Leader as the Master Political Mechanic

A biography of Mitch McConnell reminds us that ideology is neither everything nor the only thing.

January 3, 2026

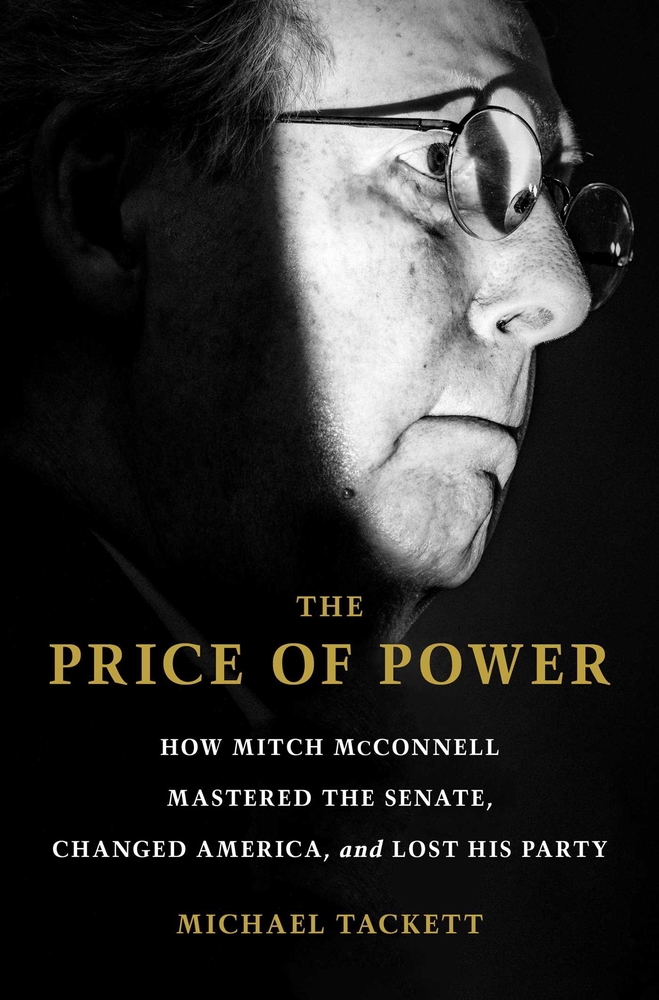

The Price of Power: How Mitch McConnell Mastered the Senate, Changed America, and Lost His Party

Love him, hate him, or grudgingly respect him.

Those are the three most common assessments of former Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell. He is a master of the game of politics, and since he has never aspired to be president does not obsess over his popularity. He is famously terse and inscrutable and likes it that way.

But the senior senator from Kentucky is a more complicated figure, and his successes as a legislator and leader are just part of what makes him an intriguing subject. Journalist Michael Tackett captures McConnell in all his complexity in The Price of Power: How Mitch McConnell Mastered the Senate, Changed America, and Lost His Party.

McConnell has helped two Republican presidents (George W. Bush and Donald Trump) implement their agendas and mostly tried to prevent two Democrats (Barack Obama and Joe Biden) from doing the same. He has accomplished this while the Senate, his party, and the country have changed dramatically. McConnell’s relationship with Trump is especially complex. The veteran lawmaker and the president loathe one another, but they have used one another to accomplish their goals.

Tackett writes: “Three Republican House speakers [John Boehner, Paul Ryan and Kevin McCarthy] were ousted, while McConnell never seen as a purely ideological figure, managed to keep his perch the way he always had: dispassionately assessing strengths and weaknesses and fashioning a path to retain his position. In his view, he tried to stop the GOP from heeding the darkest impulses of Trump, but it must be noted that he never put himself or his job in jeopardy to do so.” (xi)

McConnell’s relationship with Trump is especially complex. The veteran lawmaker and the president loathe one another, but they have used one another to accomplish their goals.

McConnell’s rise to the top spot in the Senate was anything but preordained. He grew up in a solidly middle-class family in Alabama and Kentucky. His father was a middle manager in corporate America, though that side of the family also ran a funeral home. That might explain where McConnell gets his perpetual frown.

His childhood would have been rather unremarkable had he not been diagnosed with polio before there was a vaccine for it. At the time, one of the supposed remedies was to basically stop walking for a time so as not to strain one’s body. McConnell did that, but eventually was also helped by being treated at the rehabilitation center in Warm Springs, Georgia, established by Franklin D. Roosevelt, before becoming president. It is a remarkable facility, and today visitors are reminded of the horrors of the disease and can see the equipment used to treat it, as well as tributes to survivors such as McConnell and FDR.1

While McConnell (who became a Republican as a child) never shared FDR’s politics, he shared his grit, fighting spirit, and determination to succeed. McConnell overcame many of the obstacles stemming from polio, but as he got older, he occasionally limped, had trouble going downstairs, and had some balance problems.

Tackett writes that for McConnell, polio “would remain his unwanted gift, and his haunting ghost.” (14)

Early on, McConnell decided he wanted a career in politics. What he lacked in charm, charisma, or good looks, he made up for with hard work and an ability to think several steps ahead.

After working as a legislative assistant on legal issues for Sen. Marlow Cook of Kentucky and as a legislative liaison in the Justice Department during the Ford administration and getting a firsthand look at the judicial confirmation process in which he would later play a leading role, he began his own political trajectory.

He served two terms as the judge-executive of Jefferson County, Kentucky’s most populous, which includes Louisville. He then defeated Senator Walter D. Huddleston, who was a popular, though undistinguished, lawmaker.

His father was a middle manager in corporate America, though that side of the family also ran a funeral home. That might explain where McConnell gets his perpetual frown.

McConnell ran a well-financed campaign and had a sophisticated political organization, but national party officials were skeptical of his chances, even in a year when President Reagan was cruising to reelection. What turned the tide was an ad produced by consultant Roger Ailes (who later would be the founder of Fox News) that showed a detective and four dogs looking for Huddleston, who had missed votes to make paid speeches.2

Early in his Senate career, he mostly followed the advice given to newcomers to be seen and not heard. He picked issues such as campaign finance reform (he opposed it) that nobody else wanted. But he ingratiated himself with his colleagues by helping them raise money. He used his chairmanship of the National Republican Senatorial Committee to bolster his political strength by raising money, picking candidates, and guiding campaigns.

The hard work paid off and he was elected Senate GOP leader in 2007 and held the job until last year. He has announced he will not seek reelection in 2026.

He became a leader at a time of dramatic changes in the Senate, where individual members saw themselves as free agents and less beholden to their party organization. One of McConnell’s predecessors, Senator Bob Dole, quipped that a better description of the job is “majority pleader.”

While McConnell had some clout over committee assignments and other perquisites, this was not the same Senate Lyndon B. Johnson led in the 1950s when the leader could strongarm and bully other members into siding with him.

Those wanting a more detailed look at LBJ’s legislative prowess should read Robert Caro’s Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson.3 His book relies extensively on the work of reporters-turned-columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, who covered LBJ as senator and president. (Caro never met him). Their first-hand accounts make their book, Lyndon B. Johnson: The Exercise of Power, one of the best books about U.S. Senate leadership. (Full disclosure, Evans was a friend and mentor, and Novak was a friendly acquaintance.)4

While Tackett’s book does not contain first-hand descriptions of McConnell’s interactions with other lawmakers, he talked to McConnell and many of his colleagues. A helpful description of the leader’s approach comes from Senator Lisa Murkowski, the senior senator from Alaska: “Mitch has always been very fair, just very decent when I break ranks. And it’s not to suggest he doesn’t try to encourage me in subtle ways, and he is very subtle,” Murkowski told Tackett. “I think he realized with me very early on that political influence, or pressure, was going to get him nowhere with me. And when it was really, really important, he would say. ‘This would be important to me.’ That’s always the worst.” (330)

Tackett, the deputy Washington bureau chief for the Associated Press, writes that McConnell’s success stems in part because he is “dogged and largely one-dimensional, obsessed with politics and an occasional dabble into watching sports.” (330) Fun McConnell fact: it turns out he is not a big fan of attending the Kentucky Derby, though Tackett does not explain why.

Tackett also discusses Republicans whom McConnell loathes, including Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri, for his reluctance to accept the 2020 election results, and McConnell’s fellow senator from Kentucky, Rand Paul, whom he hates in part because Paul is a libertarian disruptor and has no appreciation for Senate traditions.

When giving Tackett a tour of the Senate floor, he notes that Paul sits in the desk once occupied by McConnell’s idol Henry Clay, McConnell notes dismissively that “Henry Clay would be appalled by Rand Paul,’’ though he does not elaborate. (viii)

McConnell critics contend that he only wants power for its own sake and does not have a grand policy vision. That is not entirely accurate.

To be sure, McConnell is no policy wonk or ideological warrior, but few Senate leaders are. He has been a solid center-right politician who has tried to steer the Republican caucus to pass the most politically feasible conservative policies. Since Democrats occupied the Oval Office during most of his time as leader, McConnell has been forced to play defense and the strategist for the not-always-loyal opposition.

Tackett, the deputy Washington bureau chief for the Associated Press, writes that McConnell’s success stems in part because he is “dogged and largely one-dimensional, obsessed with politics and an occasional dabble into watching sports.”

He has had notable successes, including preventing any Republicans from voting for the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare.

But what he considered to be his crowning achievement was preventing Obama’s choice for a Supreme Court vacancy, caused by the 2016 death of Justice Antonin Scalia, from even getting a hearing, let alone a vote. McConnell cited a range of questionable historical precedents to justify what he admitted was a chance to score political points, protect vulnerable incumbents, and help the GOP win the next presidential election.

“I was prepared to take the heat for the process in order to protect my members,” he told Tackett. (240)

However, Tackett argues that there were broader forces at work. He notes that “with the Republican Party drifting hard to the right, and anger toward its leaders on the rise, McConnell’s own self-interest cannot be dismissed as a reason for his course of action.” (240)

McConnell’s leadership would really be tested during the first term of Trump’s presidency. The two men detested each other but needed one another to achieve their goals. McConnell was a loyal soldier and helped Trump implement much of his conventionally conservative agenda, such as tax cuts and putting three justices on the Supreme Court who helped overturn Roe vs. Wade and cut back the power of the administrative state.

But McConnell hated Trump’s abrasiveness, his tendency to break glass, and his isolationist tendencies.

However, it was not until the insurrection on January 6, 2021, when Trump supporters stormed the Capitol to try to prevent lawmakers from certifying Biden’s election, that McConnell publicly criticized Trump. But his break with Trump only went so far.5

He said Trump was “practically and morally responsible’’ for inciting the riot. But he declined to vote to convict him after the House impeached him. He justified his decision on the fact that the impeachment occurred after Trump left office, and that the courts would punish the former president. Also, McConnell did not want to fall on his sword and be one of a handful of Republicans voting to convict Trump when there were not 67 votes in the chamber.

Tackett writes “that rather serving as a moment of moral clarity for McConnell, it was merely a prelude to the kind of contradiction that has marked his time as one of the nation’s most powerful leaders; a strong belief that Trump had committed an impeachable offense but made a political decision that overrode it…It was likely the worst political calculation of McConnell’s career.” (308-309)

He considered his crowning achievement to be preventing Obama’s choice for a Supreme Court vacancy, caused by the 2016 death of Justice Antonin Scalia, from even getting a hearing, let alone a vote.

McConnell defended himself to Tackett by arguing that his approach, trying to challenge Trump somewhat from within the party, was more effective than that of mavericks, such as former Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyoming, who lost her primary after voting to impeach Trump.

“Where I differed with Liz is I didn’t see how blowing yourself up and taking yourself off the playing field was helpful in getting the party back to where she and I probably both think it ought to be,” he said. (309)

McConnell’s actions were politically sound but do not show much appetite for risk-taking.

Tackett’s book shows that while on many levels McConnell has been an effective leader, he is unlikely to be included in any sequel to President John F. Kennedy’s Profiles In Courage.6

1 https://gastateparks.org/LittleWhiteHouse

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcpuhiIDx3Q

3 Master of the Senate, by Robert Caro (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002)

4 Lyndon B. Johnson: The Exercise of Power, by Rowland Evans and Robert Novak (New York: The New American Library, 1966).

5 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kj5pvgXAgMs

6 Profiles In Courage, By John F. Kennedy (New York: Harper & Row, 1955).