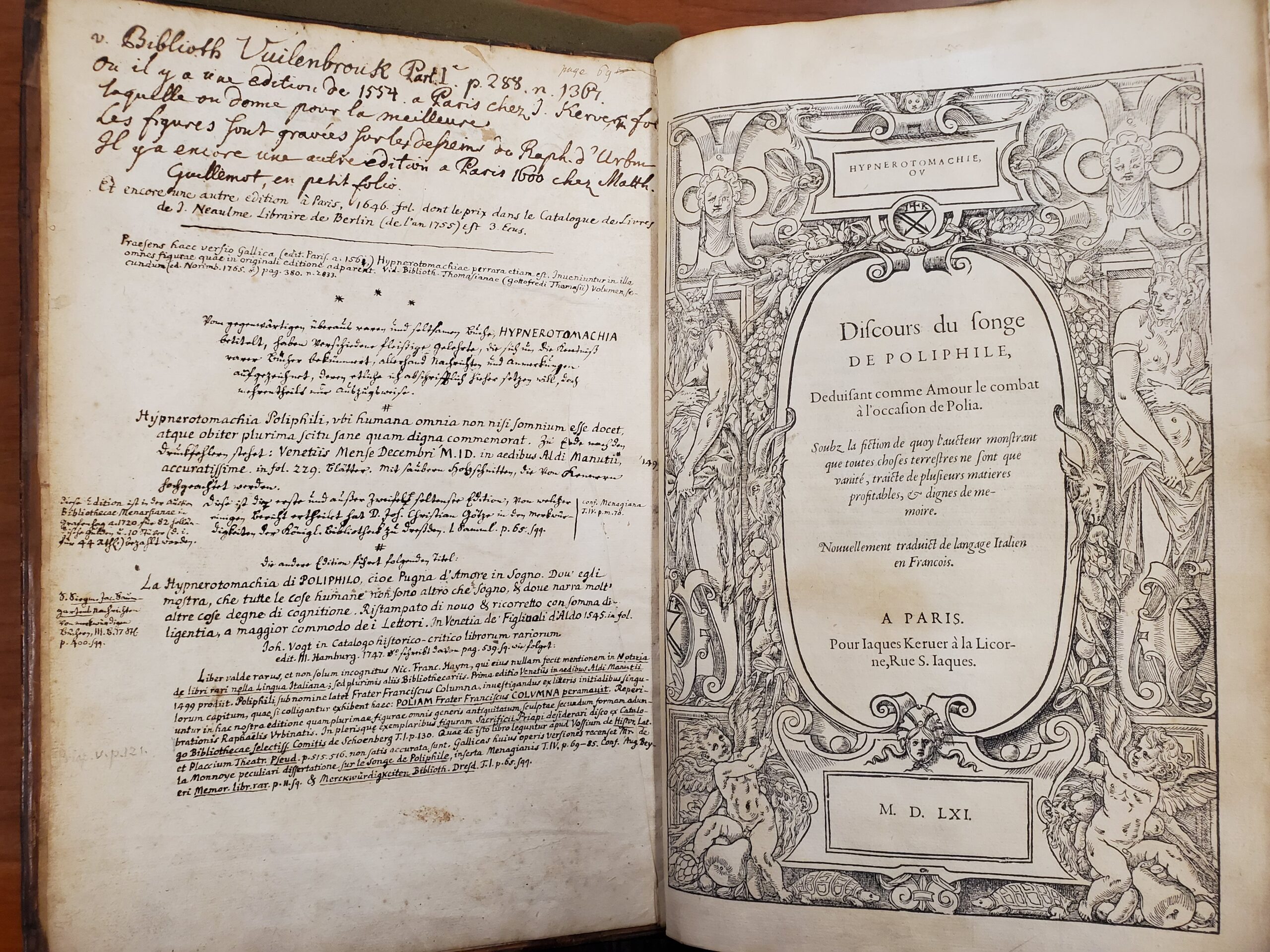

Some of the bibliographic notations in the edition in Washington University’s collection appear to be written in the hand of Paul Christ Gottlieb, castle librarian at Ansbach, Germany, where a private princely library went public in 1720 and acquired the Hypnerotomachia in 1759. Images courtesy of the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections.

“We live for books. A sweet mission in this world dominated by disorder and decay.”― Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

A book can change your life. But a rare and mysterious book, one with secrets not yet fathomed? A book like that can own you.

The Rule of Four is a New York Times bestseller on the order of The DaVinci Code, and I am reading it for pure fun. A few pages in, I am swept into the father’s obsession with the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a weird dreamscape of a book that was written in the Renaissance and has mystified scholars ever since. Consumed by his research, the father dies in a car crash before he can confirm his theories. Now his son is at Princeton, sharing a suite with an unabashed nerd who is writing his senior thesis on the Hypnerotomachia.

As the two friends are drawn—the nerd eager, the son wary—into the book’s puzzles, the obligatory dead body is discovered, paralleling the fifteenth century murder in the book and reminding us just how powerful—and distorted, and amoral—a scholarly passion can become. The Name of the Rose this is not, but as a bedtime read, it is fun and engrossing, a New York Times bestseller packed with genuine historical details about this beautiful and enigmatic manuscript I never knew existed.

Halfway through the book, I find out that last summer, our own university library acquired the third print edition of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. There it waits, just through the glass doors I enter weekly.

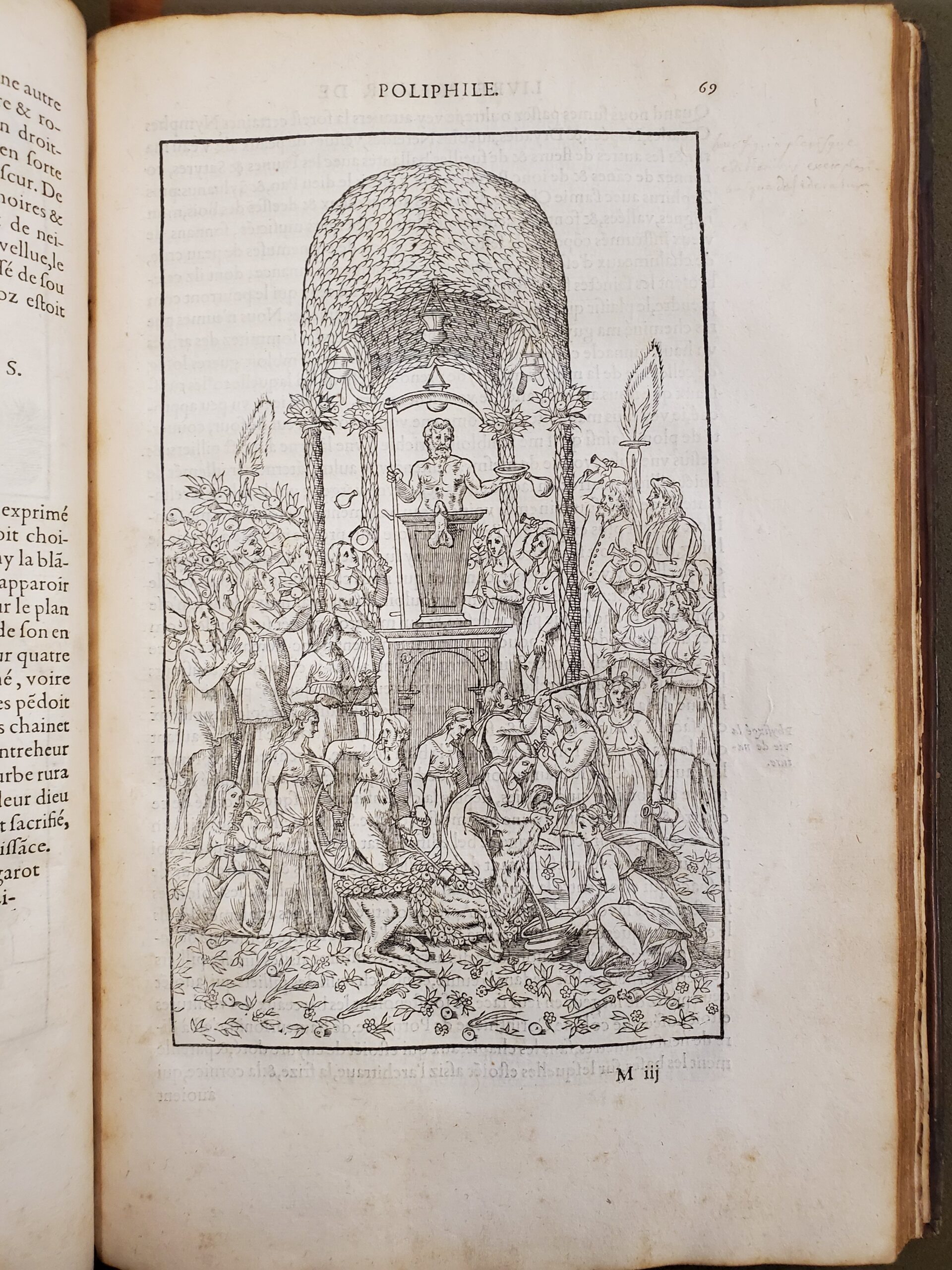

Not the 1499 original, mind you. That was printed in Venice, and copies are scarcer than red diamonds. But as compensation, Washington University’s leatherbound, gold-foiled copy, published in 1561 in Paris, has three extra illustrations. Best of all, it includes the oft-censored “Worship of Priapus” woodcut, his naked member thrust through an opening and rampant as a heraldic lion. Librarians pencil gleeful notes in the margin when the image is still present, not torn out, defaced, or obscured with a fig leaf of ink. “Worship of Priapus” just might be the most censored woodcut of the Renaissance. (Further delight, then, to know that Wash.U.’s rare books collection also boasts a single leaf from the 1499 edition: the (again uncensored) Worship of Priapus plate and an accompanying essay.)

Cassie Brand, curator of rare books for the university libraries, learned about the Hypnerotomachia years ago in a book history class. When a bookseller told her that a copy was now available, she knew how neatly it would dovetail with the library’s collection on the history of printing, its holdings on illustration and book design, and its Arnold Semeiology Collection, which includes code breaking and hidden messages. Also, it is marvelous.

Cassie Brand, curator of rare books for the university libraries, learned about the Hypnerotomachia years ago in a book history class. When a bookseller told her that a copy was now available, she knew how neatly it would dovetail with the library’s collection on the history of printing, its holdings on illustration and book design, and its Arnold Semeiology Collection, which includes code breaking and hidden messages. Also, it is marvelous.

Brand worked for months with the university’s French department and romance languages and literatures librarian to acquire it. “The book was originally published anonymously,” she explains. “However, the first letter of each chapter in the 1499 Italian edition forms an acrostic that translates to ‘Brother Francesco Colonna has dearly loved Polia.’” Does that mean that a Dominican friar by that name was the author? Or, as some scholars believe, that a more erudite Roman aristocrat by the same name wrote the book to toy with us? The book was published before title pages were a convention, so its authorship is anyone’s guess. The remarkably talented illustrator, despite creating one of the first books to be printed as an art object, was never named. Aldo Manuzio, the printer who did the amazing typography, avoided putting his seal on the book, probably disapproving of its generously sponsored contents. Having just recovered from the plague, he needed the cash.

Brand confirms The Rule of Four’s premise: that the manuscript holds more secrets yet to be decoded. “It’s an acid trip of a long dream,” she says, “and the only reason it would be so weird is so you could encode messages.” What fun, to be so lavish and hallucinate so freely. As the novel’s narrator explains, “It is the world’s longest book about a man having a dream, and it makes Marcel Proust, who wrote the world’s longest book about a man eating a piece of cake, look like Ernest Hemingway.” Twined into the 181 woodcuts, threaded through the unusually elegant typography, and tucked into the dream sequences and allegorical fantasies; the lyrical descriptions of gardens of glass and silk, ruins, dragons; the bloody sacrifices and foot fetishes and eroticization of architecture; the polyglot mix of Latin, Greek, invented Italian, Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, and hieroglyphs; and the wordplay that foreshadowed Finnegan’s Wake, are messages from the mysterious author to any readers sufficiently patient and erudite to make their way through even this sentence, let alone the book.

Scholars are still trying to prove themselves capable of deciphering those messages. “It contains not only knowledge, but, as you will see, more secrets of nature than you will find in all the books of the ancients,” promised the wealthy Venetian lawyer who commissioned its first printing. A New Republic review of a 1999 translation described the Hypnerotomachia as “hot and eerie.” (And the translator, Joscelyn Godwin, is “known for his work on ancient music, paganism, and music in the occult.”) Other bookish mysteries, like The Club Dumas, name-drop the Hypnerotomachia to add intrigue to their own plots.

What greater gift could someone leave for posterity (meaning us) than a puzzle this rich?

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.