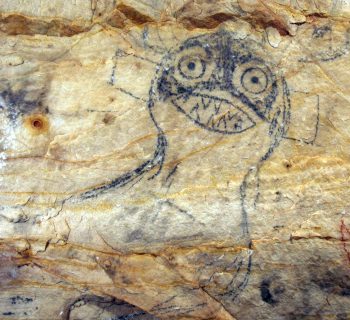

Underwater spirit at Picture Cave.

An artist held out drawings of the rock art in Picture Cave. In its pitch-black depths, beneath a woodsy, remote part of Warren County, Missouri, the cave had walls covered in red and black pictographs.

Carol Diaz-Granados, who was working on a doctoral dissertation about Missouri’s American Indian rock art, stared for a long time, unable to believe the images were authentic. But the head archaeology professor at Washington University went to the cave, and when she returned, she urged Diaz-Granados to check it out.

The black warrior holding a mace. The man of mystery, gray or dark wolf. A two-headed hawk that would make the Hapsburgs jealous. A kneeling warrior who might be shapeshifting from a serpent to a human. A dancing figure, human or animal? An antlered serpent with exposed fangs. A running man clutching his erect phallus in his right hand—a reference to a fertility rite? A birdman standing atop his defeated enemy’s body….

The pictographs were authentic. They were made around 1025 CE. They are the most detailed ancient drawings in eastern North America. And there are more than 290 of them—the largest collection of indigenous people’s polychrome paintings in the region.

Diaz-Granados and her husband, James Duncan, who is also an archaeologist and anthropologist, brought in iconography experts and studied the pictographs (with the landowner’s permission) between 1991 and 2005. They have continued researching their meaning and implications ever since.

Quietly, like water dripping down the cave’s rough walls, word of this extraordinary place’s significance found its way into academe, archaeology, native culture studies. And now Diaz-Granados’s phone is ringing and her email is blowing up, always the same alarmed message, coming from scholars and preservationists all over the country: What’s going to happen to this unique and sacred American Indian cave?

They have just found out that on September 14, Picture Cave—the hidden Lascaux of the Midwest—will be auctioned off to the highest bidder. The auction terms also note that Picture Cave is “subject to prior sale,” should there be an exceptional pre-auction offer—so this may already be a done deal.

For now, though, the bidding is open to the public, says Bryan Laughlin, executive director of Selkirk Auctioneers, and I am welcome to come watch. “We don’t envision it taking too long.”

I ask how the auction came about.

“A real-estate land appraisal only considered what acreage in Warren County was selling for,” Laughlin explains. The family had used the land as hunting grounds for fifty-three years, and they had talked on and off about selling. After hearing the land’s appraised value, they came to Selkirk Auctioneers for another opinion. Over the next eighteen months, Selkirk’s curators, keenly aware that this was not any old acreage, built a relationship with them.

I ask if there is any chance the cave will be turned over to a public institution. (I am thinking it should go to the Osage Nation whose ancestors made the art.) He mentions that he already has “a lot of private individuals who have shown interest—a few who have already registered to bid. And we do have one public entity.”

Is it my imagination, or is there less enthusiasm in his voice when he adds that last bit?

A quote flashes back to me: “Rock art is one of the only windows into the minds of ancient people.” The remark came from Dr. Brian Stewart, curator of the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology at the University of Michigan and an honorary research fellow at the Rock Art Research Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand. It was part of a pre-publication review of Searching for Petroglyphs and Pictographs in Illinois, coauthored by a friend of mine, Dr. Susan Barker, and it was such a simple summary, it stayed with me.

I wonder what he thinks of Picture Cave being auctioned off.

Stewart is in Italy when I try to contact him, but I email a link to the auction house’s description, and he replies quickly: “The idea that a cave as historically significant and spiritually redolent as this one can be auctioned off like a piece of furniture is sickening to me. There are so many ethical problems and questions, it makes my head spin.”

Auctioning off the cave is entirely legal: “The U.S. has strong cultural heritage legislation regarding federal (and obviously tribal) property, and shockingly little when it comes to private property with respect to other non-developing nations.” In this instance, Stewart says, you have “a landowner attempting to boost a property’s value by advertising a cultural attribute from which its native authors and original owners were dispossessed, with no acknowledgment in that regard.”

The Osage Nation knows about the auction; it was listed on three meeting agendas in May and July of this year. I am told a not-for-profit fund is working with them to bid on the cave. I am not sure what their chances are.

When I contact Dr. Andrea Hunter, the Osage Nation’s director of historic preservation, she chooses her words carefully, noting that they have “serious concerns” regarding the protection of burials and sacred sites and “the continuing desecration of places of cultural significance in Missouri.” This state was the homeland for the Osage peoples for 1,300 years, she adds, until “the United States government took our remaining land and forcefully removed us. Warren County, Missouri, the location of Picture Cave, contains the burials of hundreds of our Osage ancestors and some of our most sacred locations.

One of those sites is of course Picture Cave, “consecrated not only with its own intrinsic significance but also with the immense panels of rock art designating it as such. It is nearly impossible to find a comparable site in today’s American landscape.” For the Osage Nation, Hunter says, “the imminent sale of this property is another heart-wrenching chapter in the history of Osage sacred places appropriated and ‘owned’ by people who do not comprehend their true significance.”

Auctions make no guarantees.

“The owner always assured us that if they ever sold the cave, they would only sell it to a conservation entity, the Osage, or someone who would care for the cave and preserve it,” Diaz-Granados says, adding that placing a monetary value on Picture Cave “would be like placing a value on the Great Pyramid at Giza, or the Taj Mahal. Can you imagine auctioning off the pyramids or the Taj Mahal? It’s terribly unfortunate that no federal agency can take possession of the site.” She reminds me of the question that often surfaces in archaeological essays: “Who owns the past?”

We will find out on September 14.

Meanwhile, Diaz-Granados has another, more practical question: Why would a private owner want this property? This is a dark-zone cave, difficult and dangerous to enter and navigate. Nobody is going to be charging admission for families to line up to see the cool pictures.

Back in 1991, Diaz-Granados and Duncan pleaded until the landowner gave them permission to descend into the cave: crawling for twelve or so feet, then slowly, inch by inch, lowering themselves down three five-foot drop-offs. When they finally reached the floor of the cave, they made a slow arc, letting their headlamps and flashlights reveal the interior. The light hesitated: One of the pictographs had been pried off the wall. There it was, a thin sheet of rock that could smash in a heartbeat, lying on the floor of the cave.

The archaeologists convinced the landowner to allow them to have the cave closed and paid with their own money to have both entrances gated, preventing further vandalism. This was, they could see, no ordinary cave. The drawings were elaborate and vivid, highlights created with rock scraped to a bright white. They were made by torchlight, deep inside the cave, so the images would be protected from the elements. Sacred rites probably took place here. Entering a cave, for many American Indians, places you inside Mother Earth. Or, as the Mandan call her, “The Old Woman Who Never Dies.”

Back in 1996, Diaz-Granados received a grant to bring in two analytical chemists from Texas A&M University. Using the charcoal in the black pigment, they were able to date three of the pictographs to a weighted average of 1025 CE. These drawings were made almost a thousand years ago, in the pre-Columbian era.

Next Diaz-Granados obtained another grant, this one funding an interdisciplinary project including professors from six major universities, four Osage elders, a curator from the Chicago Art Institute, two artists, two chemists, and five caving specialists. (One professor was so eager to see the pictures, he charged ahead of the group, fell off a ledge, and gashed his forehead.) The participants wrote up research papers that were eventually published as Picture Cave: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Mississippian Cosmos. The book did not come out until 2015 because of a dispute with the landowner, Diaz-Granados says, but an agreement was reached over royalties.

Picture Cave is shaped like a capital C. Because the middle section collapsed several hundred years ago, the cave has two separate entrances, one to the area that forms the top of the C, the other to the area that forms the bottom. No one has yet been able to study the middle section. “If I were younger, I’d get a team to see if the collapsed area could be shored up so we could dig it out,” Diaz-Granados says, “because there’s rock art behind the collapse.”

There is so much more to learn. This cave is a Rosetta stone for American Indian symbolism from the early Mississippian culture; its history connects to the nearby Cahokian civilization whose mounds are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

One other variable at play: There are endangered Indiana bats living inside the cave. Still, their federal protection “is just words,” Diaz-Granados sighs. “Somebody with the big bucks could chase those bats out of the cave.”

She and Duncan hope to see the cave in the hands of the Osage Nation, studied only by scholars the Osage Nation approves. She can envision “pilgrimages by the Osage themselves to see this sacred cave of their ancestors.”

But she can also envision somebody “destroying the panels by chopping them off the wall to decorate their den. Or to sell to foreign collectors.”

There are quite a few wealthy buyers from other countries who scour the market for American Indian art.

They think it is worth preserving.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.