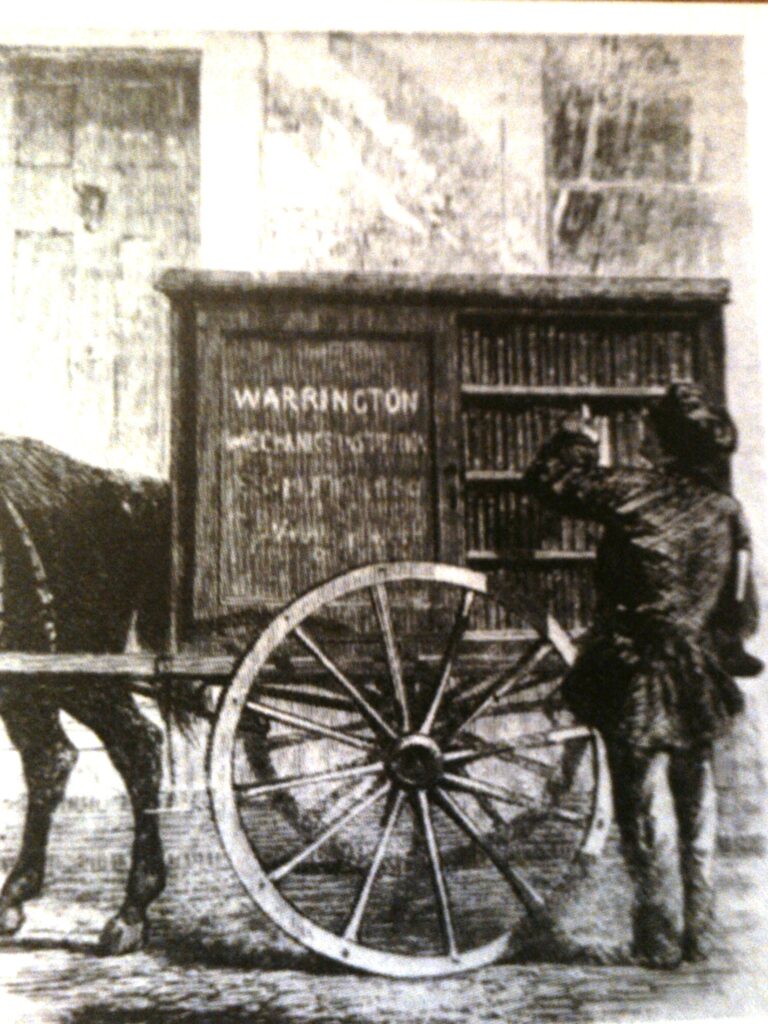

Warrington Perambulating Library, 1851. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A dinner conversation turned to favorite childhood books, and from there to the bookmobile. Everyone else rhapsodized about how much fun it was to clamber onto that library-as-bus and pick out your books. I shuddered and stared at my broccoli.

I dreaded those class trips to the bookmobile. It felt like all my classmates were trooping into my secret sanctuary. Oblivious of their trespass, they called out the names of books I had read, books I had lived inside, casting them aside or piling them up haphazardly. I would be reminded years later, when miserly vultures flocked to our yard sale, rifled through my grandmother’s favorite possessions, and asked, “Will you take a dime for that?”

Besides, I liked a library that was a place—ever welcoming, serene, a little dark and musty, spacious. Not a crowded and claustrophobic vehicle where you chose like a game-show contestant with the clock ticking, then watched the rest of the books chug away. Books let you fly, and until that happened they should stay put, so they could be chosen in a leisurely, speculative way, a few pages gently turned, back covers and frontispieces examined. The atmosphere should be quiet, almost reverent, and very grown-up. No one should bother you.

Only now do I realize what a luxury our branch library was. I talk to people who grew up in the country, or in a town that had no library, or with parents who would not drive them to one. Who would I have been? Childhood’s slings and arrows would have splintered my reedy backbone if there were no books to shield me, lend me perspective, let me soar above those tiny sorrows, and think largely.

Not to mention the boredom. In my navy-and-green–plaid world, the biggest excitements were the possibility that a teacher was PG (the aforementioned grandmother’s easily decoded abbreviation for pregnant), the chance two boys might get into a fight after school, and the school janitor showing up to sprinkle sawdust on a puddle of sick. Those Greek myths and Flossie Nightingale biographies and Dana Girls mysteries showed me it was possible to break out of a small world, to be brave, to explore.

“The bookmobile was the whole world parked on my gravel road,” Margaret Atwood recalls. If I had lived somewhere that was not ribboned with asphalt, I would have felt that, too. Now that I have shed the self-consciousness of childhood’s fierce inner life and realized I am not the only one who cherishes books and I do not have to protect them singlehandedly against bubblegum and mocking boys . . . my heart has softened toward the bookmobile.

Who first thought of putting a library on wheels? Mary Lemist Titcomb had a horse-drawn book wagon made for the Washington County Free Library in Maryland in 1905. But she was inspired by mobile libraries in nineteenth-century England, horse-drawn carts like the Perambulating Library of Warrington, which circulated in the 1850s. In the 1870s, lighthouse keepers used to wait eagerly (I picture them slashing counted days on a makeshift calendar) for sailors to bring them books. And the Jacobean Travelling Library, fifty of the classics tucked inside one giant portable book, was meant to occupy noblemen of the seventeenth century during their journeys.

Whoever the audience, the excitement came from the compressed possibilities those libraries carried with them.

“Psychologically, the wagon is the thing,” explained Titcomb (who was, of course, a librarian). “One can no easier resist the pack of a peddler from the Orient as a shelf full of books when the doors of the wagon are opened at one’s gateway.” She persuaded the library janitor to drive the wagon and warned him that there should be “no hurrying from house to house, but each family must be allowed ample time for selections.” A courtesy the nuns at my grade school forgot to extend.

The books’ appeal was not obvious to the farm families in 1905; many assumed books were for scholars, recipes, or religious devotion. Education was not yet compulsory, and though days spent breathing chalk dust do not guarantee a love of books, they do make it more likely. Titcomb pressed on, sure that the country’s future rested on a reading, thinking populace. She also knew how much pleasure could be gotten: “Through books they are lifted out of all routine of every-day life, their imaginations are quickened and for the brief space that the book holds them in thrall the colors of life assume a brighter tint.”

That was especially true in rural Maryland, where people were not in thrall to a bestseller’s list and so “chose a higher quality of literature.” I tend not to at bedtime; murder relaxes me. But in a 2013 study published in Science, participants were better at identifying emotions expressed on other people’s faces and understanding and empathizing with others’ beliefs if they had just read prizewinning literary works than if they had read romances or mysteries so formulaic and purely entertaining that they need only read along, propelled. Those were readerly works, the researchers explained, as opposed to writerly works for which the reader’s own mind filled in the gaps.

The wagon Dandy and Black Beauty pulled through Washington County soon carried a bit of writerly, a bit of readerly, a bit of everything it suddenly seemed possible to desire. Other libraries started book wagons, too, and soon they were motorized, amply funded, beloved across the States and across the Atlantic. When London was being bombed to smithereens during World War II and people could not safely visit a library, the Saint Pancras Traveling Library drove through the darkened city packed with two thousand books, its interior lights hidden by blackout curtains.

Not until the Seventies did bookmobile use begin to decline, thanks to—what a tired excuse—rising fuel costs and budget cutbacks. Today, people read less, and much of what they do read, they can access electronically or grab from one of the Tiny Libraries, which are charming but offer only enough selection for an elf. Does anyone rescue a bookmobile for nostalgia’s sake? Vintage, they sell for about $50,000. . . .

But wait—bookmobiles remain relevant. In 1996, the Kenyan government started a formal Camel Library Service with books in English, Somali, and Swahili, and camels now bring books to remote Ethiopian and Pakistani villages, a godsend during COVID. Perhaps they carry their namesake, The Camel Bookmobile, a novel about the hunger for literature and the clash between tradition and modernization.

In Thailand, it is elephants that carry the books. Elsewhere, books travel on bicycles, carts, and trains; in Norway, they float aboard a large, splendid ship. Traditional bookmobiles might be decreasing, but The Free Black Women’s Library is launching a bookmobile in Brooklyn, offering titles written by Black women. In Portland, a bicycle-powered cart lends books to people living outside. In Bangkok, there is a Library Train for Homeless Children—the idea came from the railway police, who wanted to give the kids a safe, constructive way to learn, escape stress, and avoid a life of crime. In Zimbabwe, there are donkey-drawn electro-communication library carts where you can fax or use the internet. The Internet Archive runs its own bookmobile to print out-of-copyright books on demand. In Colombia, the Biblioburro project sends two donkeys out with a teacher to bring books to children in rural villages. In Appalachia, the Pack Horse Library Project does the same.

Because how do you grow up without books?

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.