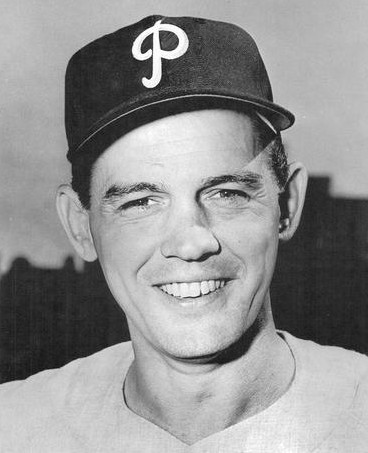

Gene Mauch, who managed four teams from 1960 to 1987, pictured here in 1961.

Gene Mauch, born November 18, 1925, was the first Major League Baseball manager I grew to know as a fan when he managed the Philadelphia Phillies from 1960 to 1968. The Phillies, my hometown team, I had to learn about on my own. My sister Rosalind, who taught me about baseball when we were children preferred the Milwaukee Braves for two reasons: first, she liked their uniforms (I liked them too much better than the hometown red pinstripes); and second, liked the Braves’ star hitters Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Joe Adcock but particularly Aaron, the Black superstar. At the time she was teaching me about baseball, when I was seven, eight, and nine years old, the Phillies had no Black superstars. That would not happen until I was twelve when Richie Allen arrived in 1964 and became Rookie of the Year. By then, my sister had lost interest in baseball. And 1964 for the Phillies and Philadelphia was a bad year.

My mother hated the Phillies with a passion. She grew up with Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers and remembered how the Phillies in the late 1940s, under manager Ben Chapman, were especially vitriolic in their racist comments and bench jockeying whenever the two teams played. Chapman was especially crude and offensive. My mother was young then, only 20 or 21, was dark-skinned like Robinson, and identified with him intensely. Chapman was from Alabama, a very unreconstructed Alabama. He was not only racist but anti-Semitic. When he was a player with the Yankees, he yelled such vicious anti-Jewish remarks to Jewish fans that a petition signed by 15,000 people was sent to the Yankee front office requesting they get rid of him. The Yankees promptly did by trading him to the Washington Senators.

Chapman was hired by the Phillies because he was good friends with the team’s general manager, Herb Pennock, another unreconstructed type. When Robinson’s Dodgers made their first trip to Philadelphia, the Ben Franklin Hotel, where the Dodgers normally stayed, would not accept the team because of Robinson. This was Philadelphia, mind you, not Montgomery, Alabama. The Phillies even thought of boycotting the series because of Robinson: Blacks should not play against Whites, so the prevailing feeling went. Twenty thousand Blacks showed up at Shibe Park in North Philadelphia for the first game of the series. That, just the Blacks alone, was twice the number of a normal audience for a Phillies game in those days. Chapman’s bench jockeying was so fierce and generated such bad publicity that Chapman was forced to take a conciliatory photograph with Robinson. He refused to shake Robinson’s hand. By the middle of the 1948 season, Chapman was gone. But even years later he defended himself as only following baseball tradition. All players are ridden hard verbally by the opposing teams; it was hazing as a kind of meat grinder, adding more pressure on the opposing players. It was all about getting an edge, Chapman explained, and getting an edge of any sort is the sine qua non of high-level athletic competition. In any case, my mother never forgot Ben Chapman or the Phillies’ thoughts of a boycott or the Ben Franklin Hotel and hated the team until the day she died in 2018. That is a long hatred.

The Phillies new manager, Eddie Sawyer, did two things: he stopped the race-baiting bench jockeying of Robinson and other Black players and he guided the Phillies to the 1950 National League pennant. The 1950 Phillies were called the Whiz Kids because they were the youngest team in the National League and their success surprised all the knowing coves. They were led by a twenty-three-year pitcher named Robin Roberts, the son of a coal miner, who won twenty games that year and pitched over 300 innings. It is unthinkable today that a starting pitcher would throw anywhere near 300 innings in a season. And remember that in 1950 a baseball season was 154 games, not 162 as it is today. This means that Roberts threw nine innings nearly every time he pitched. It is rare for a pitcher to throw a nine-inning game today. Roberts was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1976. The other remarkable twenty-three-year-old was centerfielder Richie Ashburn who later became an announcer for the Phillies and was also voted into the Hall of Fame. He hit .303. Del Ennis, another outfielder, drove in 126 runs. The stars, in more than one meaning of that term, aligned for the Philadelphians that year. Alas, the Yankees swept the Phillies in four straight games in the World Series. The Phillies would not go to the World Series again until 1980.

What I remember about Mauch, called the Little General for his command of baseball strategy, was that, like all baseball managers, he was highly driven, extremely competitive, aggressive, demanding. Baseball is a tough game played by tough men, who have gone through a winnowing process few people experience in their professional or working lives. At this time in my boyhood, ballplayers, whether Black or White, were mostly from the working class. Baseball was the way out of a dead-end, working-class job. As Ty Cobb famously said, baseball is no game for mollycoddles. There is a tendency for the casual fan to think that because the game is slow-moving with only periodic moments of overt action that it is somehow sedate. This is untrue. The game on the field is ferocious. I sometimes think the fans are not worthy of the game they paid to watch.

So, with Mauch, I learned as a boy that baseball managers were tough men because the tough men they managed would respect nothing less. Moreover, there was even more pressure on the manager to win than the players because, of course, the manager was much easier to replace than the players. If a team was expected to win, the manager had better win games or he would be looking for another job soon enough. Talk about accountability, as we do these days, as if it is an elusive quality in the work world! No one is held more accountable than a baseball manager. I learned this as I learned baseball and saw the number of managers who were routinely fired every year because they were unsuccessful.

Mauch argued with umpires incessantly, although probably not quite as much as Earl Weaver. His ability to exploit the smallest intricacy or subtlety of the game was simply astonishing. He just knew, and knew, and knew baseball better than the people who invented it. He is credited with understanding the advantages of the double switch. He could out-think any manager. He loved small ball and knew how to execute it. (In a way, he had to because before he had Johnny Callison and Dick—then Richie—Allen, he lacked any real mashers.) He won over 1,900 games as a manager which would probably have gotten him into the Hall of Fame had he not lost over 2,000. He never won a pennant. But the fact that he managed as long as he did is a testament to his skills.

In Philadelphia, Mauch is appreciated by those who remember him but is associated not with winning but losing. When Mauch became manager of the Phillies in 1960, they were a bad team. In 1961, the Phillies lost twenty-three games in a row, one of the longest losing streaks in baseball history. It was my first year of following the Phillies and I could not believe that a team could lose games for almost a month.

By 1963, Mauch managed the Phillies to their first winning record in several seasons, and fans were poised for greater things in 1964. Greater things almost happened. Mauch’s Phillies were in first place for much of the season. Finally, with a dozen games left to play, the Phillies had a six-and-a-half-game lead. The team was permitted to print World Series tickets. Then, unbelievably, Mauch’s crew lost ten straight games. It was the greatest agony I experienced as a boy. They just kept losing and losing. It did not seem real. “Why the gods above me, who must be in the know, think so little of me,” all of us in Philadelphia thought, as we witnessed one of the great collapses in all of sports. Mauch himself under the pressure became something of a madman, pitching his two best pitchers over and over trying to break the streak as they became less and less effective from extreme fatigue. He talked in a strained manner to the players in the clubhouse as the streak mounted. Not pep talks. These were professional ballplayers who were not interested in “winning one for the Gipper.” Mauch told them that they were losing money, the World Series bonuses. Even that did not work. They knew they were choking and were helpless before the fact. Mauch believed that the team could will itself to win. He was wrong. We Philadelphians always thought we were a city of losers compared to New York. Now we were convinced of it. St. Louis won the pennant and the World Series that year. The Phillies did not even finish second.

Mauch taught me something about the pain and inevitability of losing, the harshness of fate, the indifference of the gods to your pleas. Sometimes losing can have a bigger impact on you than winning. You do not have learn to live with winning but you must learn how to live with losing. With Mauch, I learned about two different types of losing: the Phillies lost twenty-three games in a row in 1961 because they were a bad team and did not have the confidence or ability to win. They lost ten in a row in 1964 because they could not endure the expectations of being a good team and the attendant pressures. It is not enough to be good. You have to be tough enough to win, not simply good. He was the first adult to drive those lessons home for me and that is why I shall always remember him.