“Doomed to a life of unending toil, Heather Simmons fears for her innocence—until a shocking, desperate act forces her to flee… and to seek refuge in the arms of a virile and dangerous stranger.”

Yep, that was my model for romantic love. The Flame and the Flower, by Kathleen E. Woodiwiss.

“A lusty adventurer married to the sea, Captain Brandon Birmingham courts scorn and peril when he abducts the beautiful fugitive from the tumultuous London dockside.”

Mmmhmmm. To my virginal twelve-year-old eyes, such an abduction was the stuff of dreams—and the guarantee of future bliss. Half a century later, I still remember the characters’ names and the author’s middle initial. Which is disconcerting. Just how firmly did that book shape me? My husband has yet to court scorn and peril, and while I love being with him, I suspect nothing we do is uncharted. Our dramas are lower-key; our efforts to figure each other out far less fraught.

In novels, romance is all valleys and peaks: a woman who is miserable, afraid, and fleeing for her life (or at least her virtue) is rescued with a single strong, sweeping gesture and set atop a pedestal. You have to be really miserable first, for it to work. Nobody tells you that. Girls used to walk around waiting to be impressed, but the stakes were always too low—and who wants to be miserable just to be happy?

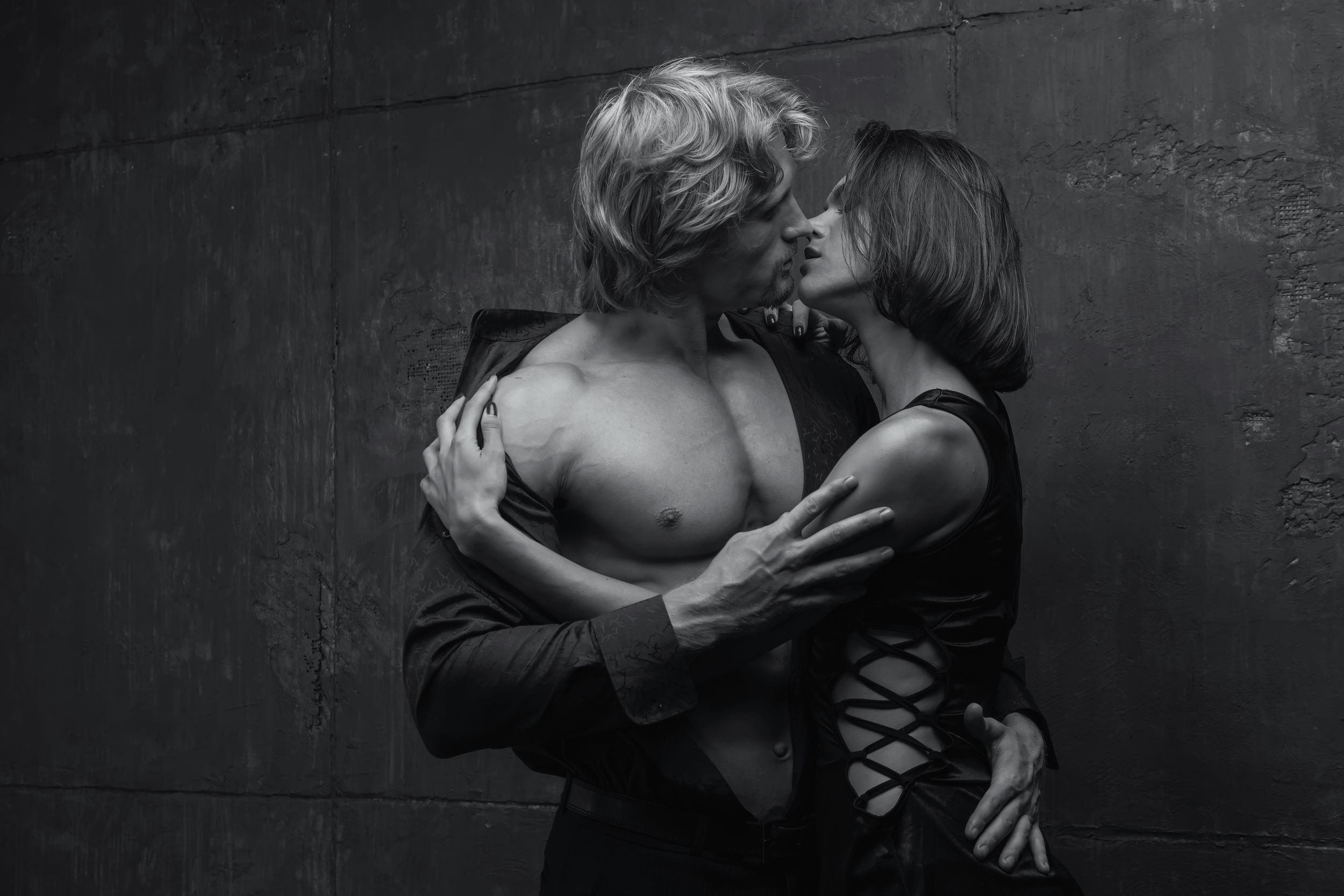

I check the book out of the library, curious to see if it still wields the old power. Will I reread certain lines until I once again know them by heart? My romance-novel phase ended a year after I read Flame, and I was soon rolling my eyes at women who devoured romance novels. Especially married women—what did their husbands think when they saw the long-haired, shirtless men their wife was ogling, even as she railed about their pin-ups?

But The Flame and the Flower was different. Your first always is.

I settle down with a cup of tea and the well-thumbed library copy. This time, I recognize the Cinderella motif right off; only the mice are missing. Heather escapes her evil, secretly jealous aunt and the baggy, dusty old dresses she was made to wear while she did all the chores. (Once rescued, a woman never again has to do chores. This is important.)

I check GoodReads and chuckle: “None of your friends have reviewed this book yet.” They would not be caught dead. The reader shelves listed are: “bodices-were-actually-ripped, my-bodice-is-ready, rape, rape-by-hero, historical-romance, kissing-books,” which should give you some idea. The reviews are scathing, far too outraged to understand what I only now realize: “The initial rape was used as a plot device to overcome the societal norms which frowned on women who consented to premarital sex.”

I was twelve, and Wikipedia did not exist. And though it is alarming to admit this, I honestly never saw their first encounter as the sort of rape we were warned about in dark parking garages. She did resist: “Her struggle pulled his shirt loose and then his furred chest lay bare against her with only the thin film of the chemise between them.” But (the little voice argues) we already knew he was her handsome hero and predestined soul mate, forged hard as steel by the sort of confidence that would only seem arrogant later, once women could have confidence, too.

Brandon thought Heather was 1799’s version of a sex worker, struggling for pay and for effect. And she, having just killed another man who definitely tried to rape her, thought she had been arrested and taken on board his ship. So, yes, it was rape, and somehow made desirable, which leaves me squeamish now, appalled by what once seduced me.

“Woodiwiss is often credited with creating the first bodice ripper or the first “modern historical romance novel,” I read. Flame sold more than 2.3 million copies in the first four years and shoved aside those prim, spooky gothics with words like “tempestuous,” “turbulent,” “tumultuous,” “lusty,” “voluptuous,” “provocative,” and “fiery,” indeed “blazing.” So I was on trend in my misguided appreciation, although one of today’s readers smartly points out that in her opinion, a bodice-ripper is an anti-romance novel. (Personally, I think this hinges on how much happens before the bodice is ripped.)

Another young reader makes an excellent point: “The illusion that their poor behavior is because of raging lust and that once their issues with the heroine is resolved they turn into sweet puppies is actually misleading and sick.” She has youth’s smug preachiness— “Brandon Birmingham needs to go sit in the corner and think about what he’s done”—but she is right. Raging lust has been invoked as excuse far too often for far too much criminal behavior. That said, the post-coital sweet puppy has, in the novel, the appeal of contrast. These days, puppies abound, and women swoon over Volodymyr Zelensky because he wants “ammunition, not a ride.”

I continue reading the reviews, chastened by their vehemence and a little ticked that nobody my age has enough guts to speak up. A novel does not rack up forty-two printings without cause. Today, Flame is a time capsule, with women hurling it across the room instead of sneaking it under the covers. But you cannot judge even a steamy, overwritten paperback by standards that fell into place half a century later.

Do I sound defensive?

When Brandon learned that he had, er, deflowered Heather, he was shocked, then brusque, assuming she was scheming for his fortune. Young women cannot fathom this, because who does that, in an era when women make more than men? They say he should have stepped outside the assumptions of his class, canceled his engagement, and married Heather the instant he realized she was a virgin (which would, incidentally, have killed the plot). Yet they declare her weak. They see Brandon as a jerk, missing the fact that he is soon besotted with her and broadsided by this unprecedented loss of control, troubling for men of the 1970s or 1799. When it becomes clear that Heather is pregnant (one of those miraculous one-act-of-intercourse conceptions that happen only in novels), the two marry but both refuse further intimacy, too proud to relent.

This builds the suspense quite nicely. But the book’s oldschool romantic psychology—for a man, the moody combination of masculinity and tenderness in a time when neither is allowed to exist on its own; for a woman, the art of being feisty and docile at once, and wily always, getting one’s way without letting him know he has lost the upper hand—is lost on younger readers. As is the fun of the long, breathless wait for the next coupling. One calls Brandon “a crazy mo’fo” and Heather “a complete disappointment who never grew a pair.” (Interesting, that even now testicles are seen as prerequisite to courage.) I would like to point out that Heather makes her cool disdain for Brandon clear and will not be led, owned, seduced, or cajoled, but skimming page after page, I see how, to modern eyes, the emphasis on her softness would obscure her courage.

The conventions have changed. Gender constraints have shifted, almost reversing. The psychology of personality has changed (today, someone would put Brandon on an antidepressant), and how men are expected to behave has (thank God) changed.

I keep reading, impatient with the lush, formulaic writing that once charmed me, until I reach the part of the novel I cherished most: the gentle, teasing intimacy between them, once they finally admit they are deeply in love. From there on, they take turns rescuing each other.

Those passages still leave me smiling, though they cannot redeem the past or render the ploys of early historical romance palatable. The Flame and the Flower was written in 1972. By 1978, New York Magazine was already noting the tension: was the exploding popularity of the historical romances that followed in its wake some sort of backlash to what was still being called “women’s lib”? Or was it “a front-rank exploitation of women’s new demands for sexual fulfillment and fantasies which can help them achieve it?” All the reporter knew was that when Avon executive editor Nancy Coffey received Woodiwiss’s manuscript, “she couldn’t put the damned thing down.”

How to explain that to young women today? How to convey what it was like to grow up in a world that privileged virginity, a world in which a woman’s passion was still not expected to equal a man’s, and it was great fun when it did. A world in which there was supposed to be a bit of combat, because the woman must be won, and a bit of mystery, because the brooding hero must be understood, his tender inner workings opened. The characters are, in other words, seducing each other. But for a generation that clicks and swipes, they are doing this in ways that are far too stereotyped, misogynistic, overcomplicated, and just plain exhausting.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.