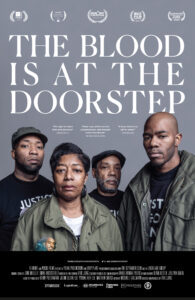

The 2017 documentary The Blood Is at the Doorstep is getting new attention during the George Floyd protests, and for a brief time is available on YouTube for free. Blood is directed and produced by Erik Ljung, a filmmaker and Director of Photography who has produced content and short documentaries for the New York Times, VICE News, and the Wall Street Journal, and who won a Midwest Emmy for his work on public television. This was his first full-length documentary.

The Blood Is at the Doorstep is the story of a family’s search for justice for Dontre Hamilton, a young Black man diagnosed with schizophrenia, who was shot 14 times and killed by a Milwaukee police officer in April 2014. This happened in the middle of weekday, in a small park outside a Starbucks, near City Hall and the performing arts center. Police had already been called on Dontre once, who was merely stretched out in the park, and found no violation. When police were called a second time about him being there, they went to the person who complained and told them to stop calling.

Then Officer Christopher Manney went to the scene. According to the film, Manney already had complaints of excessive force, vulgar language, and sexual assault on his record. He apparently tried to frisk Dontre without due cause, and said they scuffled. Manney hit Dontre with his baton in the ribs. When Dontre turned away he had the baton, perhaps accidentally. Manney ended up shooting him 14 times, from far enough away that there was no gunshot residue or powder burns on the body.

The film contains audio of Manney screaming for help afterward on his radio, as well as photos of him at the scene. Though Manney asked his backup when they arrived, “How bad is it, am I gonna live? Are my brains pouring out?”, the only mark on him was a “laceration” on his thumb, the sort of nick you get when you cut yourself with your own fingernail.

The Milwaukee Police Department would not reveal Manney’s name initially, and it tried to get out front with the story, saying Dontre was homeless and had an armed-robbery conviction. Neither was true. They also claimed he was mentally ill, but they had found that out only after interviewing his mother for 45 minutes alone in a police car the night of his death.

Any investigation of wrongdoing by Manney would be done by the police themselves or their surrogates. (The Milwaukee Police Chief grouses to the documentary crew, “For some people, if an investigation does not lead to a police officer’s arrest, it is not believed.”) Dontre’s father, a veteran, says he has always been on the side of the law, and he thought there would be due process. Instead, he says, “The door was shut in my face.” Manney was not disciplined or charged.

And, so, The Blood Is at the Doorstep becomes about Dontre’s mother and brother Nate, as they become activists to change the system in a city that has paid $30 million in police brutality settlements since 1958. In doing so, they meet and represent many who have lost relatives to police violence. Nate starts an organization called The Coalition for Justice, and we see him grow ever more confident, skillful, and outspoken over time.

By the family’s efforts, Manney is fired after five months. The Chief admits to the documentary crew that Manney “violated core competence” by approaching Dontre aggressively and laying hands on him, but that it is up to the Milwaukee District Attorney to figure out criminality. In response to the firing, the President of the Milwaukee Police Union calls the Chief a “coward” and says Dontre caused what happened to him. The union votes no-confidence on the Chief.

Nate Hamilton pushes for Milwaukee police to receive Crisis Intervention Training. The Chief tells the filmmakers, “My officers know how to size somebody up, and if they need a specialist they can get one. But It’s stunning to me that there’s not a social problem in America that apparently can’t be solved by more training for the police.”

Meanwhile, Ferguson happens, and protest builds in Milwaukee. The county sheriff warns that “anarchists” intend to lead “blockades of the highway system.” Governor Scott Walker says he intends to call in the National Guard. It all looks like today, in miniature.

The Milwaukee County DA says Dontre’s death was “tragic” but that he cannot be swayed by emotion. No charges are filed, because the officer’s baton was “a deadly weapon,” so lethal force was justified. The DA admits that when revolvers, which hold only six shots, were standard police issue, officers were trained differently. Two shots at most would be fired, then they would stop to assess. The 14 rounds that Manney shot with his semi-automatic pistol could be fired in less than three seconds.

Manney appeals to get his job back and says he has PTSD. Nate grimaces at the irony and tells a crowd, “The whole system has a mental problem.” Jesse Jackson takes the case to “the federal level,” and Hillary Clinton mentions Dontre in the 2016 presidential campaign. But while Manney is “permanently discharged,” he never faces charges. He is granted 75% disability from the department for his PTSD, plus more on top—$5,600 a month, for the rest of his life. Jeff Sessions kills the federal inquiry into the case.

The documentary closes two years after Dontre was shot. Nate Hamilton watches media reports of another Black man killed by police, after a traffic stop. There is rioting, fires, police lines. The young brother of the dead man wants to know why those who are supposed to protect the community are killing them instead.

“This is what you get,” he says, gesturing to the riots in the background. That was four years ago.

I spoke with filmmaker Erik Ljung by phone today. He said he moved to Milwaukee, one of the most segregated cities in the US, in 2008. After the Dontre Hamilton shooting, he saw “people online bashing the family and taking their script from the police, throwing the Hamiltons under the bus.” He introduced himself to the family at a rally and ended up spending three-and-a-half years working with them on the documentary, with no budget or backing.

“Storytelling seemed like the best way to raise awareness and have an impact,” he said.

Over time, as Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and others died at the hands of police, the project “became much bigger than what we started with. People were more willing to listen and understand what was going on from a different perspective.” Viewers “came to love the family as I did, and the film changed a lot of peoples’ minds,” because it “takes a fair look” and includes the voices of police and others. “We try not to interject with our own editorializing,” he said.

As we spoke Ljung was driving to Milwaukee to march with Nate Hamilton. He said some in the US did not like gestures of protest, such as silent kneeling, but now “they don’t like [the George Floyd protests] either. At some point, people have to take a stand and say enough is enough.

“Nobody wants this, but this country needs racial justice, legally and financially. Protest leads to tangible change.”