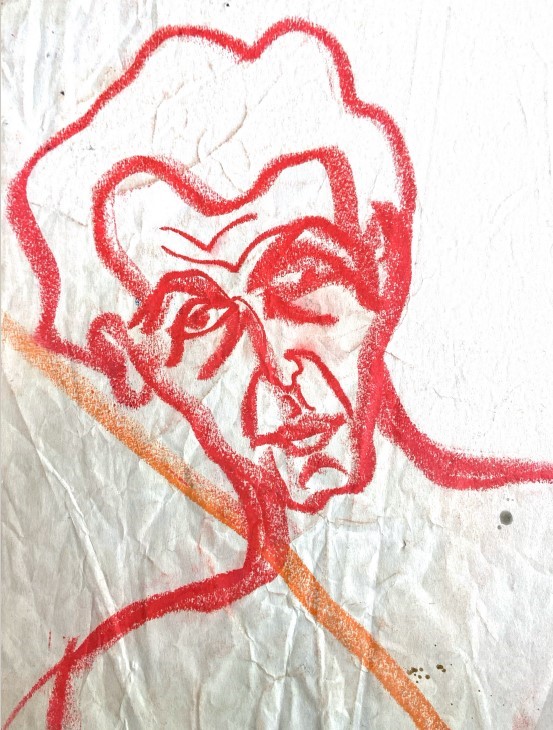

A sketch my friend is pretty sure Eddie made, many years ago in Chicago

What does a musical artist do in the midst of a bloody war? Eddie Balchowsky was twenty-one and planning on a future as a concert pianist. He had studied three years at the University of Illinois (before getting booted because he had broken into a music studio). He wound up in Chicago, working as a singing waiter. And when a friend said he was going off to fight Franco’s fascists in Spain, Balchowsky turned uncharacteristically quiet.

He knew the portent of fascism in Europe. He knew Hitler hated Jews. And he knew what it had felt like to grow up the only Jewish kid in Frankfurt, Illinois, slugged both verbally and literally as “the dirty Jew.” His mother had always told him to turn the other cheek. Now he had a way to fight back.

He sailed to France (the United States was staying out of this war, its citizens’ passports stamped “Not Valid for Travel to Spain”) and spent the night in a farmhouse. Young men poured in—by midnight, seventy or eighty crowded close—and a man he was sure was a Basque smuggler took them over the mountains single file.

He was given no uniform, helmet, or shoes, and scarcely any training. What does a musical artist do in the midst of a bloody war? When Paul Robeson came to Spain to sing for the troops, Balchowsky accompanied him on the piano. The rest of the time, he carried messages and drew maps. He hung out with the Brits and wound up brokering the peace in squabbles between the Welsh, Irish, English, and Australians. Once he clambered up to a machine-gun nest to sketch the enemy and drew their fire instead. Once the tassel of his beret was shot off. Once he was crawling, dust from the ricocheting bullets flying into his eyes and nose, and he saw a paperback on the ground called Death Takes a Holiday.

Irony is not lost on an artist at war. As the fighting intensified, he rejoined his young, idealistic American comrades in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, hiding in an olive grove until the signal came to head for the front. In the mountains of Aragon, they tried to dig a trench but hit solid rock. Before dawn, Balchowsky was ordered to go back down the mountain, find the food truck, and bring back a barrel of coffee and a bag of bread.

The minute he stood up, a sniper hit his right arm with a machine gun’s explosive bullet, and he went down. Two stretcher bearers ran toward him, but one was hit. The other wrapped a tourniquet around his arm and yelled that he should go down the hill—but he was so disoriented, he ran up instead of down. Another soldier shoved him in the right direction, and he tumbled down the hill toward an ambulance.

At least eighty men had dug into that hill with him. Only six survived.

By the time the American volunteers left Spain, half the original 3,200 had been killed. They had lost the fight. And Balchowsky had lost his future. His right wrist was shattered, and his right hand had to be amputated.

“The weird thing is,” he later told a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, “when I realized I wasn’t going to have a right arm anymore, my reaction was, ‘Well, this is going to be interesting. Now what are we going to do?’”

He floundered for a while. It took seven years to fully recover from the injury, and he tried drinking away the pain—drank so hard that a friend suggested heroin as the safer alternative. It brought the same glow and ease he had felt with the morphine in the hospital, and soon he was thoroughly addicted. Finding and buying the stuff while eluding the law earned him the nickname King of the Alleys.

But Balchowsky never stole, just made and sold art every time he needed cash. He sketches were often one continuous, bold, rhythmic line. In time, his work would hang in exhibits at galleries and the Chicago Art Institute.

Meanwhile, he was playing the piano again. In the men’s room of a bar, he had glanced down and found, crumpled on the floor, the sheet music for Bach’s Chaconne in D Minor, arranged for the left hand only. “If that’s not a sign,” he thought, “I don’t know what is.”

He smoothed the music and stuck it in his pocket. Any time he could find a piano, he practiced with his left hand. In time, he got a job as custodian at the Quiet Knight, a club played by Charles Mingus, Sun Ra, the Talking Heads, Bob Marley, Muddy Waters. Steve Goodman played “City of New Orleans” for Arlo Guthrie there. And as soon as he finished mopping, Balchowsky noodled on the same piano, starting softly with Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” then sliding into rousing songs of the Spanish Civil War.

Acquiring girlfriends, wives, and daughters along the way, he lived what the rest of us politely (and perhaps enviously) call a bohemian life. In the documentary short Ed & Frank, his freedom is contrasted with the money-obsessed suburban life of Frank Rossiter, a salesman of air-filter machines. British documentary artist Denis Mitchell assembled the short from footage left over after making Chicago, and according to Variety, created “a small masterpiece.”

Balchowsky’s lifestyle had its romance. But it also meant periods of homelessness, nights curled up in a friend’s bathtub to sleep, periods of depression so deep he had to be hospitalized. None of that tore away his kindness. He sketched train platforms, people, anything in the seams of life. Often he would walk down the street drawing and scribbling poems on newsprint, then tossing his work over his shoulder in one of the alleys for someone else to enjoy. What mattered was always the moment.

Once, hauled in by Chicago’s finest, he teased the officer who would be fingerprinting him by putting the stump of his right arm into his mouth, giving the impression he had swallowed his own hand. When the cops finally dethroned the King of the Alleys, he spent two years in prison. There he met Paul Crump, a man on Death Row for killing a security guard during an armed robbery. Balchowsky introduced him to poetry, sang him Russian and Spanish songs, wangled him a Remington typewriter, and edited the rough passages that would become Burn, Killer, Burn!, a semi-autobiographical novel that helped win Crump a stay of execution.

Lots of people had reason to love Balchowsky, including a friend of mine who met him through her boyfriend. They hung out in a large, arty, irreverent circle, and when she ran into him again years later, he knew her and hugged her instantly. He shows up in Fares: Chicago Taxicab Portraits as one of Chicago’s iconic characters. He was interviewed by Studs Terkel. Skip Haynes and John Jeremiah wrote “For Eddie” for him. He inspired Jimmy Buffett’s beloved “He Went to Paris.” Tom Waits met him and never forgot: “He was excellent. And the song he played over and over again was called ‘Without a Song.’ You know that song? Bob Dylan quoted it one night at an awards ceremony: ‘Without a song, the road will never bend/Without a song.’ [Eddie] would slam that hand down on the piano, and he’d do the low chords, and then he’d slam over and hit the octaves, then he’d get it in the middle there. It sounded huge. He sounded like Horowitz. He actually did have a nub on the end of his stump. It was like a little finger, so he could pick up a little bit with that.”

The first time Eddie Balchowsky died, folk singer Bruce “Utah” Phillips was so verklempt, he sat down and wrote “Eddie’s Song” in tribute. Weeks later, he picked up the phone and heard Balchowsky’s voice.

“Where ya calling from, Eddie?” he asked, recovering.

“Chicago,” said Balchowsky, who had called to explain the confusion.

“Hell, dead or in Chicago, it’s all the same to me,” Phillips tossed back.

The second time Balchowsky died, it was more than a rumor. But this time, nobody could believe it. His life had finally come together. He had a successful show at the Prairie Street Gallery. His art was on the walls and menus of Oprah Winfrey’s new restaurant. Diane Weyermann had made a documentary about him.

Yet on November 27, 1989, Edward Ross Balchowsky stepped onto (fell onto?) the subway tracks, leaving everybody who loved him reeling. Could he have been that sad?

The owner of the Busy Bee Restaurant, a Polish diner where Balchowsky ate oatmeal every morning, held an informal wake. Hundreds of people showed up. Utah Phillips sang “Eddie’s Song.”

His grave marker is in Forest Home Cemetery’s Anarchists Row, aka Martyrs Row. You can imagine the 2 a.m. debates those ghosts have. One of Trotsky’s secretaries is there, along with members of the Socialist Workers’ Party, unionists, politically active artists, and intellectuals of all stripes, activists who protested the Vietnam War. And there in the middle, Eddie Balchowsky, who cared about so much, he is impossible to label.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.