I have been thinking about relative dangers, recently, since everything now seems like a calculus of risk. I also want to be able to give my children perspective, as their isolation continues, a graduation has been canceled, and their futures teeter. Those who have been shocked at the sudden humbling of our economy and stature might still resist the idea that the United States will not continue to be the world’s sole superpower, but none of us know what is about to occur.

I have been thinking about relative dangers, recently, since everything now seems like a calculus of risk. I also want to be able to give my children perspective, as their isolation continues, a graduation has been canceled, and their futures teeter. Those who have been shocked at the sudden humbling of our economy and stature might still resist the idea that the United States will not continue to be the world’s sole superpower, but none of us know what is about to occur.

I have been pretty lucky in my life, so far. That is relative and simplified, but, for instance: I was born in Saigon, Vietnam, as an American, so my family could leave when the American war got up to speed, and I never had to serve in that war. I grew up in a town in the American heartland, like other towns all over the country sinking into oblivion, and we were poor after a time, but my mother had the education and inclination to help me set up the shop of my own mind.

Joining the army was by economic coercion, but it was the Cold War so I never was put in a position to have to kill for distant policies. I also was not among the 11,019 active-duty US military personnel who died in the years I served, from terrorism, murder, suicide, illness, or training accidents. The injuries I got were repaired or subsided. I left thinking I could work for anything I wanted, and maybe was invincible. My undergrad college was mostly paid for by the army, and I have bought homes with VA loans.

I finished college, which involved some luck, and got a graduate degree, with support, at the place that was right for me. People have wanted me for relationships and friendships. My wife and I had two healthy, smart kids who have been a joy to raise. I have often been slightly underemployed, but the work was solid, and I have never been on unemployment. For 25 years my life’s work—learning—has been the same as my jobs, so I have never been bored.

When I compare my life to my parents’, I feel I have had more luck, overall, which is to say accidental privilege. In this, I am the last Boomer.

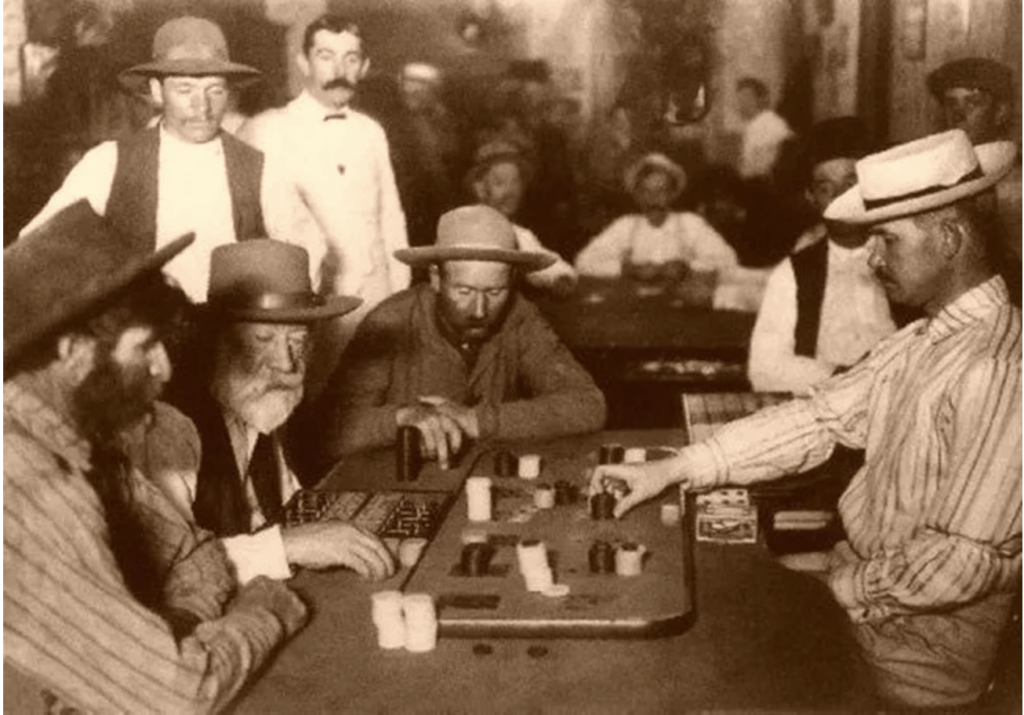

An older friend said his father used to tell him when he was young, “Boy, I went out and got mine. You’re gonna have to go out and get your own.” I laughed at that because I never had a father, and it sounded male, rude, comic—and possible. Getting your own may be a lot harder now, though I believe in my kids. They tease me about my concerns; my elder son says he wishes they had it even harder, since there are no challenges left and everything has been discovered. He wishes there were privateers still. Those were the days.

He reminds me of when I was little. My cousin Betty, an older woman with jet-black dyed hair, would come to our house with her mother, my Great-Aunt Bert, in the back seat of the car. I am not sure Bertha, who was born in 1889, could get out, so Betty and my mom would stand in the lawn and gossip for hours. (Really they were probably discussing how my mother was going to save my silly life all on her own with few resources.) God it was boring—so boring I had to climb a tree, knowing it would make Aunt Bert crazy with worry. I was no sooner off the ground than she would start shouting from the car in her ancient rasp, Get down! Be careful! You’re going to get hurt! You’re going to fall!

Of course I climbed higher, high as I could, and hung by my knees from a branch, like a bagworm, because she was over-concerned, so old she did not know anything, and I was young and blessed with luck. The whole thing was hilarious.