(Shutterstock)

Boy, did I get schooled fast. After reading article after article about how we are blasting artificial light into the night sky, erasing stars, confusing plants and animals, and confounding astronomers, I learned that there are now “dark sky” towns dotted around the world. My little town seemed a natural for this project, filled with farmers and others who lived close to nature. Surely they missed those midnight-blue skies we saw when we moved here fifteen years ago, that clear darkness studded with diamond stars that took my breath away? Venturing onto NextDoor, I asked, blithe and earnest, if anyone had ever suggested the dark sky idea.

“No thanks!!!!!!!!!!!!” came the first reply.

“Are you high,” someone wrote, feeling no need for a question mark.

“What???”

“Hahahahah. Wtf!!!”

There were more polite responses—one gentleman wrote, “I like this idea from an environmental standpoint, but as someone with glaucoma I dislike it from a night driving standpoint.” I quickly clarified: no need to get rid of street lights. A friend who is a retired science educator reminded me that the biggest problem is lights that shine upward, rather than down onto the street.

Several people wrote that their neighbor’s motion-detecting light could flood a stadium. Or that “what was a dark rural area” is now “as bright at night as any city and so the telescope doesn’t get used much anymore.”

Heartened, I went too far, posting again to say that “light pollution’s increasing by 10 percent every year for the past decade. France now has curfews on outdoor lighting; Ireland has dark sky parks. All the artificial light disrupts sleep cycles, and lots of critters get disoriented….”

“I’m speechless!” someone zapped back. “Nobody cares about what France is doing! Stop already!”

Someone else: “@Bob im speechless that you would not care about this.”

@Bob: “why????”

Okay. Here is why. The problems mentioned by (not me! stop getting mad at me!) darksky.org are glare, excessive brightness, the skyglow over lit-up areas, the amount of light shining where it is neither intended nor needed; the cluttered grouping of light sources. In other words, night lights—which ought to be small beacons of comfort—are promiscuous and inefficient. Artificial light accounts for 10 percent of our energy use, yet most of it is wasted—and does damage.

Seven years ago, scientists took measure and reported that 80 percent of the world’s population (and 99 percent of those in the United States and Europe) lives under skyglow. Put more starkly, “the majority of children born in North America today will never see the Milky Way.”

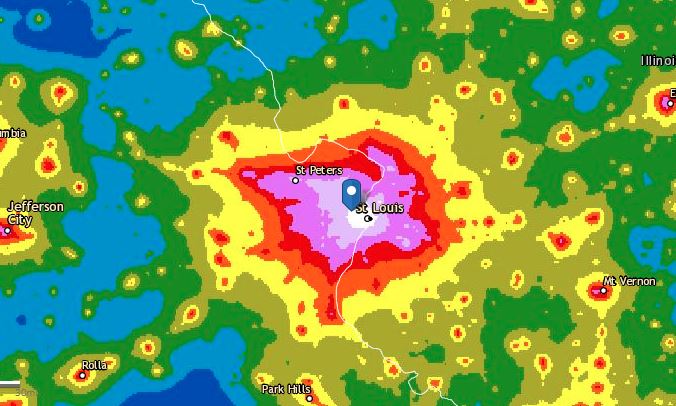

Here is St. Louis on an interactive map of artificial night brightness.

Moffat, Scotland, would be black or dark gray, not white and pink, on this map. A certified dark sky town, Moffat goes even further, switching off nearly all of its artificial lighting for two weeks every winter. “Do you need a link?” teenagers ask pubgoers, restoring the Victorian tradition of link boys who carried a lantern to guide people through London’s dark, foggy streets. (Have you ever noticed how often technological innovation moves us away from relying on other people?) As the Scottish teens lead the way, they point out the Pleiades, brighter than halogen against the black sky. Contrary to the usual reflexive assumption, there is no more crime than usual. But there are more bonfires and nighttime nature walks, and there is candlelit theater.

The rest of the year, artificial light returns, but it is carefully placed, colored, and angled. Without light pollution, barn owls and hedgehogs breed more often and more successfully. The bats sigh with relief, too. Zoologist Johan Eklöf first realized their plight when he went out to tally Sweden’s bat population and found church belfries floodlit. Curious how the bats responded, he looked at old records. In thirty years, half the area’s colonies had disappeared.

Eklöf’s new book, The Darkness Manifesto, looks at our fear of the dark. He chronicles the various sorts of damage we have done, unwittingly, as we battled that natural, instinctive fear. And then there is the extra layer of damage done just to extend our days by several more hours so we can easily keep working, buying, and attracting one another to entertainment districts and car lots.

Grasshoppers swarm like crazed mobs around the lights of Las Vegas and fry themselves to death. Dung beetles can no longer see the stars they use to navigate. Moths die of exhaustion without ever managing to find a partner or lay any eggs. Baby sea turtles head toward glowing cities instead of the moonlit sea. Wallabies give birth so much later in the season, their food is gone. Coral is bleaching out and failing to reproduce, too disoriented to synchronize its gamete release. The pollinators we need to sustain our food chain are dizzied by our klieg lights. Primates can muddle through, but nocturnal animals are having trouble functioning at all.

And humans? We pore over articles about insomnia, pop melatonin supplements, and suffer the fatigue, anxiety, depression, and other health effects of poor sleep and light pollution. “Exposure to light during the night can disrupt circadian and neuroendocrine physiology, thereby accelerating tumor growth,” notes neurologist George Brainerd. Circadian rhythms, thrown off track, can lead to depression, insomnia, cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and cancer.

Surely that is overstated, like most pharmaceutical rattlings of possible side effects? I hate drapes, so we have shutters only on the bottom half of our bedroom windows and our bedroom is never truly dark. I feel perfectly fine.

Yet when I think of cloaking the entire world in velvet darkness, something inside me relaxes.

I think, too, of all the poets and philosophers who stared up at a dark, starry sky, drawing comfort and inspiration from its vast beauty.

Soon all we will be able to see is our own murky reflection.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.