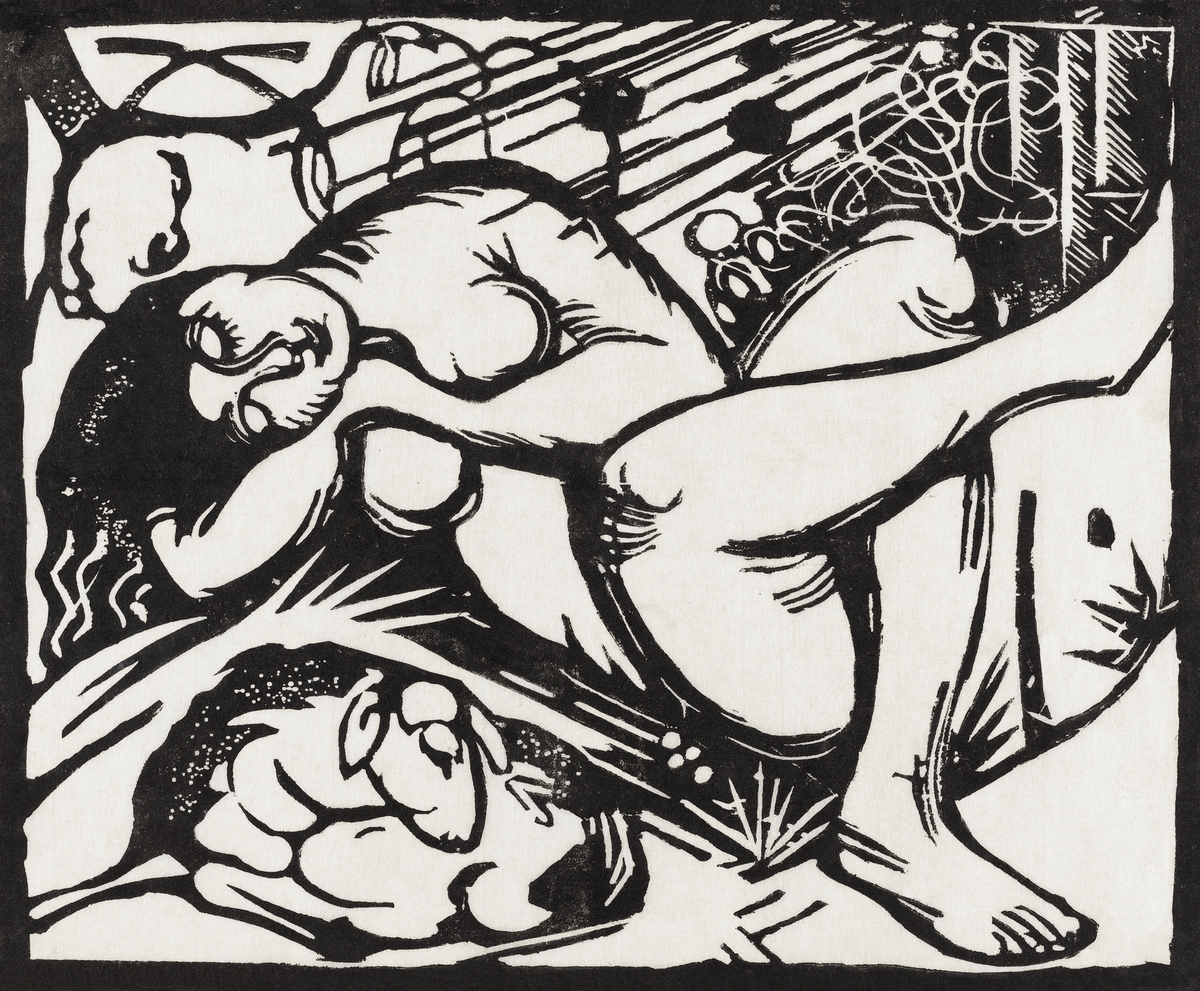

“Sleeping Shepherdess” (1912) print in high-resolution by Franz Marc. (Original from the National Gallery of Art. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.)

One of the last wells of mystery is about to dry up. Tech’s latest promise is to engineer our dreams. By rehearsing with VR, zapping certain parts of the brain awake, and cueing it with whispered dream prompts, sounds, even smells, we will be able to rid ourselves of nightmares and implant dreams that make us happy, help us learn, and enhance our memories.

So much for creativity.

Google was born of an anxiety dream. Terrified that he had been accepted into Stanford University by mistake, Larry Page dreamed that he could download the entire web onto some old computers. He woke up, did a little calculation, and realized his dream was plausible.

The sewing machine was invented after Elias Howe had a violent nightmare in which he was captured by cannibals and given twenty-four hours to invent such a machine. He failed, so they stabbed him with spears that had a hole in the tip—and when he woke up, he realized he needed a needle with an eye to create a lock stitch.

Einstein came up with the Theory of Relativity after dreaming of cows jumping back from an electrified fence. (They all jumped at once, but the farmer saw the motion in a wave because of where he was standing.)

Mary Shelley dreamed Frankenstein; Dimitry Mendeleev dreamed the periodic table; Niels Bohr dreamed the structure of the atom; James Watson dreamed DNA’s double helix. More recently, the acclaimed writer George Saunders dreamed the first four or five lines of a story, got up to write them down, and finished the story at three in the morning (then spent a year revising).

Can we engineer any of that?

We are not even sure what is this stuff that dreams are made of. Repressed feelings, traumatic memories, cosmic guidance, or just bits of the day that need to be discarded? The neuroscientist David Eagleman theorizes that “dream sleep exists to keep neurons in the visual cortex active” while our eyes are closed. If we did not have those wildly visual dreams, neighboring senses would sneak up at nighttime to annex territory in the brain’s visual cortex for their own purposes.

Others think of dreams as simulations of conscious experience, improvised with scraps of memory like the set of a low-budget high school musical. The scenery is then animated by the parts of the brain that coordinate physical movements and generate emotions. In other words, our dreams are a biological version of VR, originating in our bodies. They even take plot cues from what we feel or hear as we sleep, maybe weaving an ambulance siren into the dream story as a muezzin’s call to prayer or a grade-school teacher screaming at us. The act of dreaming links physical sensations to the brain, and it brings highly charged, unconscious experience fleetingly, enigmatically, closer to consciousness.

We dream so we will not go mad. Dreaming freshens our brain, consolidates new information, and solves problems for us. Non-REM sleep recaps the day, helping our brain decide which memories to hang on to. REM sleep goes deeper, and it can bring catharsis or at least a clue to anxiety, guilt, or grief we were trying to suppress. Do we really want to mess with that?

People plagued by nightmares would give anything to make them stop. But going to the nightmares’ root cause feels healthier than just engineering them away. Engineered dreams could help us learn more, better, faster. But we already have a few hacks for that: reading over what you most need to learn right before you fall asleep; jotting dreams in a notebook to draw insight from them. “If you can dream it, you can do it,” Walt Disney once announced.

Short of a pyrotechnic orgasm, there is little as exciting as a great REM dream, vivid and gratifying and just bizarre enough to untie you from reality. Our dreams and their possible meanings so fascinate us that writers have to be warned not to use them as a plot device. That is just a cheap shortcut, an attempt to control what ought to unfold organically.

So is dream engineering, it seems to me. The studies I pull up are all from here, the land of the American dream. Which is a practical, hyperconscious, hyperrational sort of dream. We mistrust the elusive, the mysterious, preferring the approach in the 1984 movie Dreamscape. A man, more psychic than dream engineer in today’s sense, learns how to intrude on REM sleep to manipulate its content. He then joins a project hijacked by a government agent who intends to use it to assassinate the U.S. president—under the pretext of curing him of his nightmares about nuclear war.

The ability to enter, manipulate, or cancel a dream has consequences.

Nothing is more personal, or more fragile, than a dream. We borrowed the word as metaphor for our deepest longings, our highest ideals, the sort of dream Martin Luther King engraved upon the nation’s collective mind. “If your dreams don’t scare you, they are too small,” Richard Branson once remarked. And Eleanor Roosevelt promised that “the future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.”

I doubt she would feel the same way if someone had programmed her dreams ahead of time. The enterprise feels so . . . leaden.

People are excited that VR will allow them to induce dreams about flying, which “has traditionally been difficult, because we often dream about things we’ve done during the day.” But why would we need a literal prompt when for centuries, we have dreamed of flying as a metaphor for freedom, release, euphoria?

Dream engineering does work, in the technical sense. After fifteen minutes of flying in virtual reality, people were more likely to dream about flying. Stick electrodes on the skull to stimulate the motor cortex during sleep, and people have more dreams in which they are running, surfing, or playing football. (Which could be lovely, albeit bittersweet, for people living with paralysis or other limitations.) Dormio, an electronic device developed by Harvard and MIT researchers, uses sound prompts, and after hearing that they should “think of a tree,” two-thirds of participants had dreams that included some reference to a tree.

Next, Dormio wants us to record our own prompts, so we can dream about whatever we choose. How limiting. Are we giving up on the chance of wisdom or catharsis? I would rather trust my unconscious to script my dreams; it knows what I need better than I do.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.