I nearly missed marrying my husband. Our first real date (after a mutual, happily married friend gathered her single college friends in a hopeful blind double date) was for an art exhibit, and he was picking me up late on a Sunday morning. Earlier the same morning, I met a friend for our weekly ritual, coffee over a shared copy of the Sunday Times. We both showed up as usual, and ninety minutes later, I headed home to change out of my sweats and maybe comb my hair before this date I was not yet sure whether to be excited about.

When I pulled up in front of my apartment building, he was already there. God, I thought, what a dork. I blurted that I just needed to change, appalled at somebody so rude he would show up thirty minutes early. When I reemerged, he asked mildly, “Did you happen to forget to change your clock?”

He had been waiting half an hour. I later learned that his best friend, a lawyer far more cynical than my sweet historian, told him I was just trying to ditch him, nobody would forget Daylight Savings that completely. (Let alone blithely meet a friend who had also forgotten.)

Now I remember to reset our vintage clocks, and we grin about it—but I still struggle with the mnemonic. “Fall forward” sounds just as likely to me as “Fall back.” Frequent questions on Google console me: “Do we gain or lose an hour?” “What does Daylight Savings mean?” “What time do the clocks go back 2021?” We cannot even decide if it is Daylight Saving or Savings. The Congressional record contains bills to initiate emergency daylight savings, permanent daylight savings, two-hour daylight savings, and year-long daylight savings—interspersed with bills to repeal daylight savings altogether. Hawaii and most of Arizona ignore daylight savings time, and at least fifteen states are ready to make it year-round the instant the U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigieg, gives the okay.

Ah, but Russia already tried that, in 2014, and soon reneged, worried about rousing schoolkids and keeping them safe on pitch-black winter mornings. There is also a parental struggle to coax little ones to bed on long, bright summer evenings. It is impossible to make this work for all of us.

“Lose an hour in the morning, and you will spend all day looking for it,” observed Richard Whately in 1854, skewering our childish wails about gaining or losing an hour. Time is never truly lost (just ask Proust). Clock time is what messes us up. And changing the clocks to soak up more light throws off our circadian rhythms, the circadian rhythms of wildlife, the bloom time of plants, the rhythms of the planet. There is even a name for this—“circadian misalignment”—and in the human body, it can knock both the immune system and the metabolism off kilter, as well as causing a bit of insomnia or sleep deprivation. Traffic accidents increase slightly on the Sunday or Monday of the time change. Medical errors increase. Heart attacks, strokes, and atrial fibrillation increase. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine reported that, in a survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults, sixty-three percent were in favor of fixing the time year-round instead of changing it seasonally.

I was never a fan of clock time to begin with, and this bid to steal a little extra sunlight, trick nature itself for the sake of productivity, feels arrogant. Also absurd. A hint can be found in the annual confusion and griping and the grumpy trudge around the house spinning the hands of every clock not yet wired to the great computer in the sky. Even the name is wrong: You are not actually saving anything. You are shifting clock time, is all. If it is lighter at night, it is darker in the morning, and your body will not be fooled.

But civilization gets stuck. We do something for a good reason (daylight savings was an effort to save coal during World War I) and then continue to do it without much reason at all, and a few folks point out the silliness, only to be trounced because it is now Tradition. I would volunteer my remaining days on Earth if you let me wipe the slate clean of every needless and confounding rule, every law banning consensual oral sex in matrimony or drinking beer from a bucket.

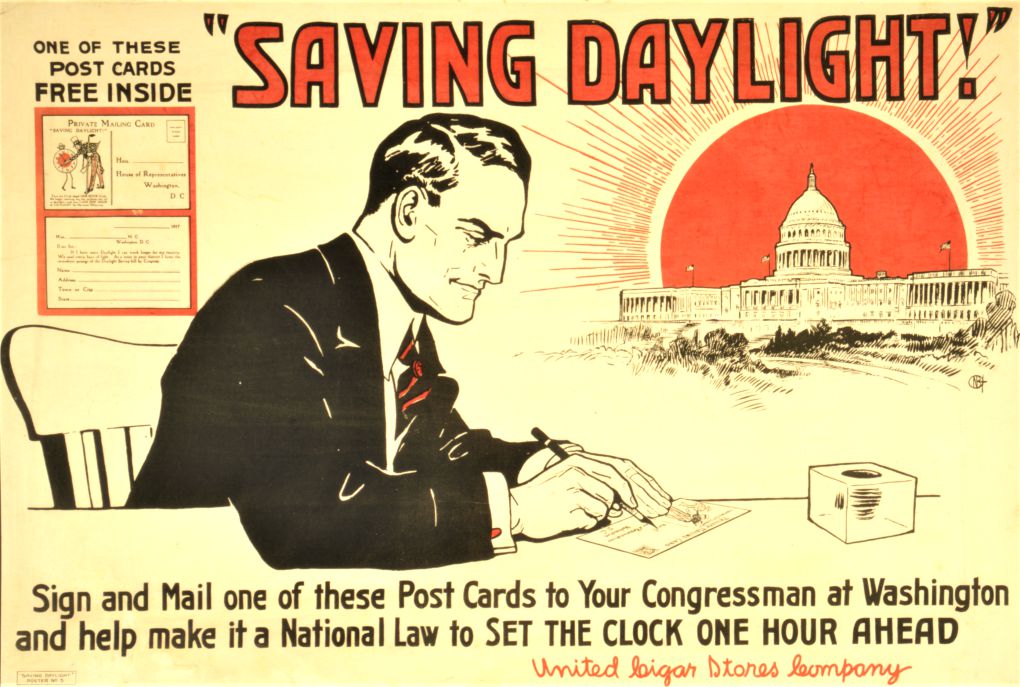

I am alone in this, though: We have sought for centuries to standardize our days. Ben Franklin took a jab at lazy Parisian shopkeepers who did not unlock their doors until the sun had been up for hours, then wasted pricey candle tallow in the evenings. In 1895, a New Zealand entomologist proposed daylight savings time so he could catch more bugs. In 1907, a British builder, William Willett noted “The Waste of Daylight” and urged changing the clock, because “when daylight surrounds us, cheerfulness reigns.”

The New York Times called Willett’s idea “little less than an act of madness”—yet ten years later, launched a year-long campaign to make it happen. People found it confusing from the start, prompting newspapers to publish diagrams and the Washington Times to insist, a bit too strenuously, “There is no need for the slightest confusion.”

The first period of daylight savings ended, but we returned to the practice for World War II. I always heard we did it for schoolkids catching buses (which made no sense) or for farmers (who hate it, especially dairy farmers, because cows do not run on clocks). Entire continents (Asia, Africa) spurn this silliness. Morocco gives it up for the month of Ramadan. Jewish ceremonies still use the ancient method of dividing daylight into twelve increments, as do monasteries on Mt. Athenos. Instead of hours, which last sixty minutes no matter what, there are twelve increments that change with the seasons: As the day lengthens, they grow longer, and in winter, they are shorter.

With so many people working and studying from home, experts predicted that the transition would be much easier on our bodies this year. Clocks no longer loom over us, scaring and scolding like mechanical nannies. We do not have “the added stress of a commute,” noted Dr. Eve Van Cauter, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. We are not contending with the Fascists who insist that the trains run on time or the White Rabbit bosses who embed gigantic timepieces in their psyche.

Also, more and more of our timepieces are computerized, meaning that if you are young and spurn antiques, you might have shown up on time after the clock changed without even realizing that the clocks had changed. So perhaps it will all grow simpler, and we will not have this sort of thing to contend with:

Central European Time is usually six hours ahead of North American Eastern Time, except for a few weeks in March and October/November, while the United Kingdom and mainland Chile could be five hours apart during the northern summer, three hours during the southern summer, and four hours for a few weeks per year.

Why do we continue to do something so dramatic and confusing instead of simply adapting the start of our day to the sunrise? It would hardly kill us to open our businesses a little later in the dead of winter, staying snug in our beds or bathrobes, then start the day a little earlier in summer, all without touching time itself. Why not honor our circadian rhythms and do what the light suggests? We proceed as though it is business that is sacrosanct—yet when business stands to profit, we are perfectly willing to bend time. It was candy companies that lobbied to extend daylight savings through Halloween, and legislators from Idaho backed an extension because longer summer evenings meant higher sales of French fries. But these little pockets of potential profit are dwarfed by a digital marketplace that runs 24/7 anyway.

Other countries simply hang a siesta sign or shut down the pubs in late afternoon without a second’s hesitation, and Manhattan goes quiet on summer Fridays. Back in 1810, the Spanish National Assembly Cortes of Cádiz officially moved certain meeting times forward in summertime without altering their clock time; they left it up to businesses to change their opening hours. All very relaxed.

Here, the newest federal legislation, which aims to make Daylight Savings Time permanent, is called the Sunshine Protection Act—as though we could. The sun will burn itself out eventually. Maybe it will happen on one of our annual twenty-three-hour days or twenty-five-hour days. The sun will pay no heed.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.