When violent unrest broke out in Ferguson on August 9 and several ensuing days after the police killing of a young unarmed Black man, my mother, who lives in Philadelphia, called me, vaguely under the impression that all St. Louis had become unglued. Surely, my house must be under siege.

When violent unrest broke out in Ferguson on August 9 and several ensuing days after the police killing of a young unarmed Black man, my mother, who lives in Philadelphia, called me, vaguely under the impression that all St. Louis had become unglued. Surely, my house must be under siege.

She has visited me many times over the years I have lived in St. Louis but always found St. Louis’s geography to be labyrinthine to the point of incomprehensible. I explained to her that Webster Groves, where I live, is not near Ferguson. I made the analogy to the 1964 Philadelphia race riot which was confined, as these occurrences usually are, to one section of the city. In 1964, the riot occurred in North Philadelphia and my family lived in South Philadelphia. That’s about the same, I explained, as the distance between Webster Groves and Ferguson. I remembered in fact that my life was quite normal during that turbulent time, as my baseball-crazy friends and I were more concerned about the Phillies than we were about the riot that was taking place on the other side of the city. We thought 1964 was going to be the year of the Phillies, and the year Richie (Dick) Allen, the team’s new third baseman and first black superstar. It was the year of Richie Allen, who won the Rookie of the Year Award; it was not the year of the Phillies.

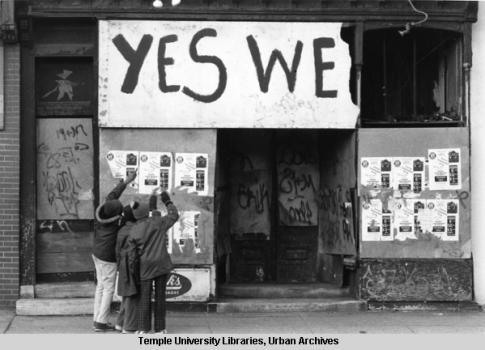

The Philly riot started Aug. 28, 1964, and lasted for about three days, severely damaging the main business corridors of black North Philadelphia, Columbia and Ridge Avenues. It was an area of Philly called the Jungle because it was black, very poor, and, especially, for a young boy like myself, dangerous because of the terrible gangs ruling the streets. When my South Philly friends and I would go to a Philllies game at the old Connie Mack Stadium (or Shibe Park), we always had to be careful, cautious, and mix in with crowds of whites coming and going. If we were isolated and stopped by any young black boys of North Philadelphia we were going to be in big trouble, being on their turf. It was an impossibly long way to run back to South Philadelphia. One had to either fight against very long odds of success or give up all of your money and probably get messed over for good measure. My friends and I loved the Phillies enough to take a chance occasionally. But only occasionally.

If there was any place in Philadelphia where a race riot was going to happen, well, the Jungle was the place. South Philadelphia was the oldest black community in Philadelphia but North Philadelphia was the biggest by far. The riot changed things, impoverished the Jungle even more than it already was, made it possible for the famed rough-riding cop Frank Rizzo to become police commissioner and eventually mayor, exploded the claims of the white liberals and reformers that race relations in the city were getting better. The riot was also one of the elements that laid the foundation for Philadelphia eventually getting a black mayor.

At the time of the riot, my mother was dating a black policeman (a man she would later marry) and so I was exposed to a different view of the event than I might otherwise have gotten. I met many black policemen at the time because my mother’s boyfriend was very popular and they were always coming by our house looking for him or meeting him there. These men always impressed me enormously. They were absolutely at the time the smartest men I knew. (They played chess, they read books, they listened to jazz, and they encouraged me to do the same. They just seemed to know—and know and know—about life and people. They were men who knew how to take care of themselves and their families.) They complained bitterly about the racism in the police department, how impossible it was to get a promotion, and they often seemed deeply frustrated. Their views about crime and criminals did not differ much from their white colleagues—overall, cops do not trust people, probably because they constantly see people at their worst—but their overall attitude and approach were somewhat different. They did not like how many poor black people acted but they understood why they acted that way. They had some sympathy with the riot—the people in the Jungle were shafted by high rents, high food prices, high-priced cheap goods obtained on the installment plan, poor public service—but mainly thought the people were hurting themselves. The Black cops did not like being called Uncle Toms and flunkies for The Man and stuff like that. Who would? They mainly saw the riot as a way of making a lot of overtime to supplement their salaries. They talked about their wages all the time. Perhaps this helped them to think of their very political job of maintaining order in an apolitical way. Oddly, they did not think it was especially dangerous to work the riot area. (Only two persons were killed as a result of the riot, so, compared to Watts in 1965, Detroit in 1967, Newark in 1967, Philadelphia was “mild” as was the 1964 Harlem riot where only one person died.)

I think some of us of mildly revolutionary and leftist tendencies in the late 1960s thought the Philly riot was “lame.” The young, the immature, and the romantic can think that resistance is pretty, an aesthetic, because such thinking doesn’t require you to think about what it costs and how it brutalizes everyone nearly as much as the brutality that generates it. Because of these men, as a boy, I thought being a policeman was a good and honorable job. I still do, understanding the political necessity of it. And their working stiff’s view of the politics of the riot was to affect me deeply because I admired them so. Other than athletes, black policemen were my first heroes.