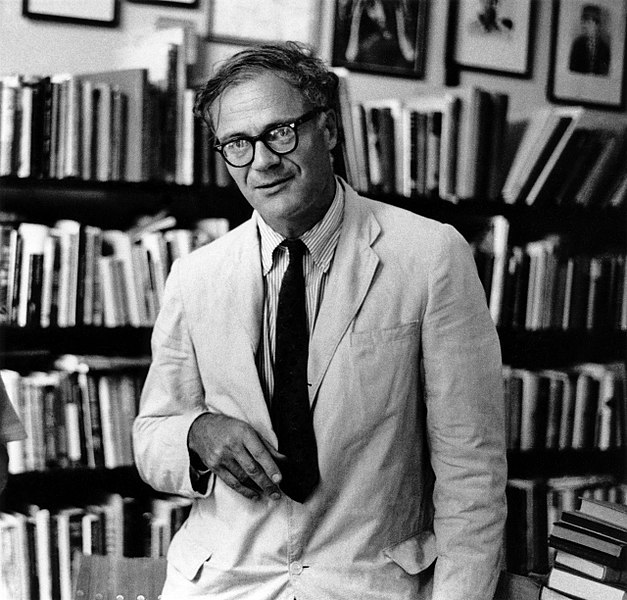

American poet Robert Lowell in a 1965 photo. (Photo by Elsa Dorfman, Wiki-CC)

I fell in love with Lowell in college. I was seduced by the tautness of his language and the grandiosity of his worldview. “Skunk Hour,” with its painterly composition of a town in Maine, its deliberately pedestrian observations, its seemingly casual lineation, the incorporation of a song lyric (“Love, O careless love”) that at the time, I did not know was allowed in poetry. I remember listening over and over to a recording of Lowell reading it, his voice scratchy and surprisingly, to my young ears, southern (“spar spire” is the phrase he seemed to love pronouncing, by the way he slowed down as if to savor the alliteration). Or “Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket,” which I discovered in an anthology, Eight American Poets by Joel Conarroe. It was originally published in Lowell’s early collection Lord Weary’s Castle, which I went out and bought after reading that anthology; I loved discovering the oft-anthologized poem in its original collection, in a slim volume of verse, among peer poems that have not been as often anthologized. I remember how impressed I had been by the declarativeness and the musical punchiness of its opening line, the way it dropped a strange-sounding name and then left me hanging (“A brackish reach of shoal off Madaket–”), and I remember how taken I was with how my then-poetry teacher was; she read that opening line out loud to us, slowly and emphatically, without rushing in to comment on it, just letting the phrase linger in the air of our classroom. This is how love takes shape, in a bed of circumstance.

I remember the pressed nature of that early love, but I want to consider one of his last poems, from his last book Day by Day, a tome usually indicated as the most elegiac of his already mournful oeuvre. In returning to Lowell (I confess I have not read him regularly for at least a decade) I was struck by “Epilogue,” a poem I had read before but had not taken to heart.

Even at a glance, the poem differs from what I remember about Lowell’s poetry. Its variable line length instantly shows a freer musicality, one that shows it is not beholden to holding the line, as it were, with earlier verse (and much of that in English language poetry tradition, in which a prosodic unit is repeated from line to line, such as iambic pentameter, resulting in text that looks uniform; such uniformity has long been equated with rigor, rather than what it can also be sometimes—a guiding lamp for the poet and something to help him steady himself as he feels his way through the dark of a consciousness.)

I am also struck by the simplicity of its sentiment in its opening lines, and the ease with which it puts on an accent: “Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme—/ why are they no help to me now / I want to make / something imagined, not recalled?” Here Lowell is writing about writing poetry, with the stakes being nothing less than the scale of a life spent doing so. Subtle choices make these stakes manifest; the accented “blessèd” both makes me read it the way he had read it aloud as two syllables but also hear the older English tradition at the same time that he contrasts it with more contemporary idiom: “why are they no help to me now.” The task of writing is shown to be as desperately needed as oxygen. Lowell lets so simple a grammatical unit as “I want to make” exist on its own, so that as we read, we get a grasp of it. the language is simple, the drama is high, but the effect could only be created by a poet who could hear the musical resources of an historical and contemporary sweep of time. I pause here, to appreciate the time I just spent thinking and rewriting my description of only four lines of verse!

It is this kind of attentiveness that Lowell’s verse brings out in me. For that, I still hold a careful love.