If you are old enough to have seen Pulp Fiction in a theater when it came out, brace yourself: this is the film’s 30th anniversary. We are as removed from its 1994 release as we were in 1994 to the 1964 release of A Hard Day’s Night, starring four young guys from northern England who had blown up The Ed Sullivan Show earlier that year.

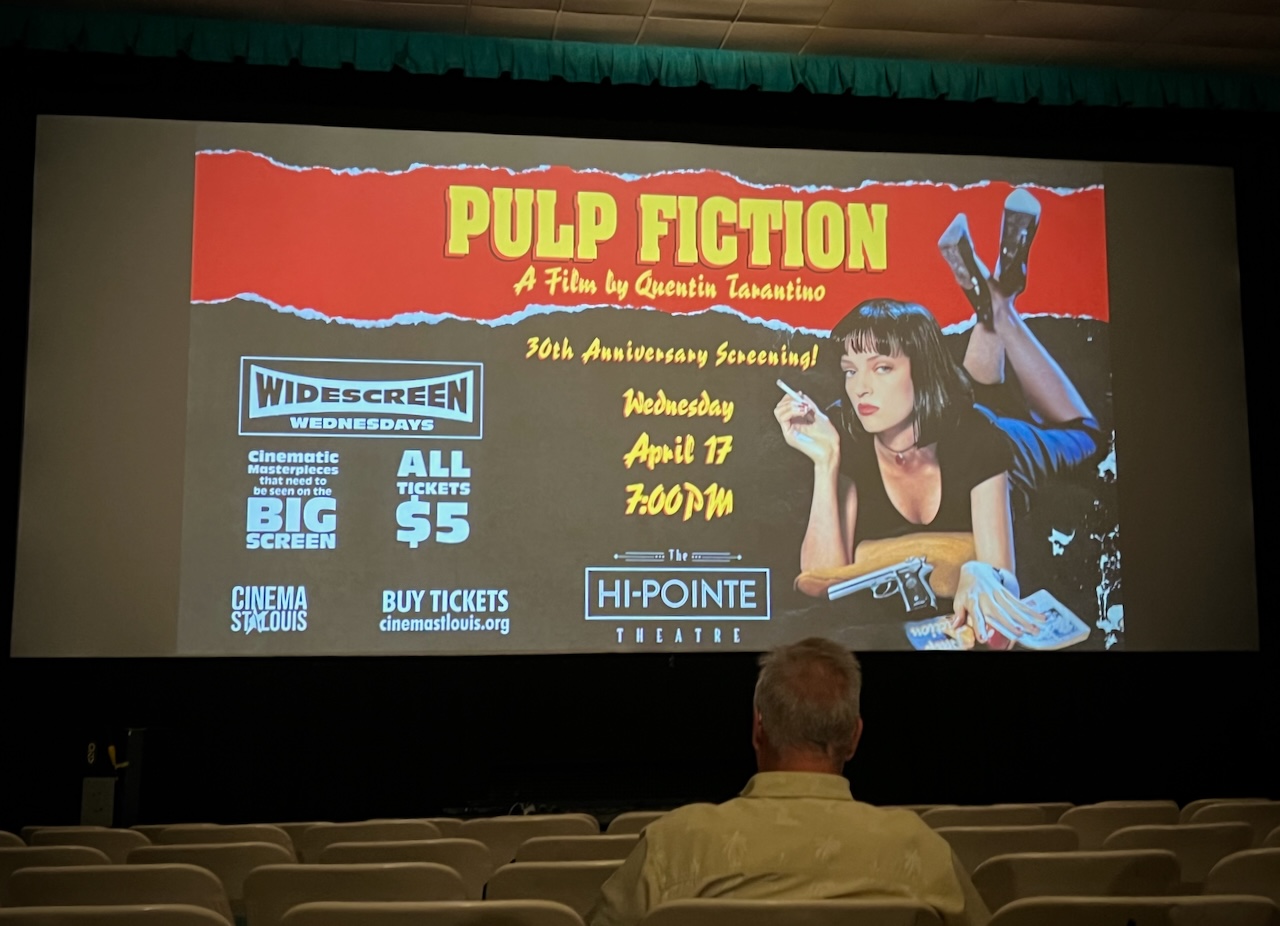

Pulp was shown again on the big screen this week, for its anniversary, at St. Louis’ historic Hi-Pointe Theatre, built in 1922. Tickets were five dollars, a refreshingly quaint sum. Before the show the AARP logo filled the screen, leaving some young people in the audience puzzling over the acronym, and for fun the theater played one of those “let’s all go to the lobby” cartoons. Everything about the event amplified the idea of age.

So does a film as old as all that hold up? Yes. Sure, the opening credits are interminable, and when Harvey Weinstein’s name appeared a bunch of people booed then laughed as if he were an old-timey movie villain. But there is hardly a scene that does not still engage; the performances are excellent and the soundtrack is still groovy.

The best parts of the film might be called “I don’t know what you call that” scenes, in honor of Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) telling Vincent Vega (John Travolta) she does not know “what you call that” uncomfortable silence between them on their night out.

The thing that cannot be named is earned emotion, and it makes the film. I had forgotten that after their dangerous attraction and terrible experience, Vincent, shot a little gauzily, blows Mia an unseen kiss when she goes back in her house. It is not romance, really, but something more like foreshadowing, a hint that Vincent is too soft, hapless, or distractable to be in his line of work. But his tenderness is almost redemptive.

Tarantino has so often seemed juvenile when he speaks, and so loves his gory violence, that I am always surprised how masterfully he can make quirky dialogue do the emotional work of a stage play. (Speaking to Charlie Rose after the release of Pulp, Tarantino compares his method to that of a novelist.)

Take Chris Walken, please. I was wary of my judgement at the screening because I have watched parts of the film so many times on YouTube, none more than the infamous watch scene with Walken, which cemented his reputation as a much-loved weirdo. Would my reactions be based on the 30-year-old film or on multiple memories of viewing isolated clips and knowing how they have become twined with our culture?

The watch scene does little more work narratively than to give Butch (Bruce Willis) motivation to value his father’s watch over everything, which later puts him in danger. But the four-minute monologue by Walken is indispensable as earned emotion. On the big screen, with his dyed hair, gaunt face, and dirty fingernails, he looks like an embalmed corpse. His face in closeup is huge, his bulging eyes somehow both dead calm and too intense. His talk of service, honor, and the wisdom of history—“this time they called it World War Two”—delays the bad thing everyone knows is coming, even the first time they see it.

That delay is emotional buildup. Tarantino’s most identifiable feature as a writer-director is his characters’ talking, talking, talking, often followed by violence triggered not by the talking, really, but by accident, coincidence, or stupidity.

I read somewhere that the watch scene was shot half a dozen times with different emotions for each take, and the takes combined to create its effect. At the beginning of the scene there is a moment when Walken gasps with laughter at some private amusement over how people once used pocket watches instead of wristwatches. The weirdness of it is so deeply buried in the character’s inner turmoil that something happens in me too, because it is emotionally true. Even if I cannot understand why he reacts so strongly, it is beautiful. (Walken’s character then passes through suppressed rage and emerges into racism and scatological stupidity, which breaks the tone and provides catharsis.)

Forrest Gump, which made 300 percent more box office than Pulp Fiction the same year, earns nothing like the emotion of that scene.

Tarantino has said Pulp was made by combining three well-known stories, “which we’ve seen a zillion times”: The gangster who is asked to take his boss’s wife out; the boxer told to throw a fight; and what two hit men do all day after they kill some guys.

The writer Vivian Gornick would call those “situations,” not stories. She says that only by structure, order, shapeliness, and expressiveness, one leading to the next, that a buildup of texture is achieved, and that this is what stirs us and causes us “to feel, with powerful immediacy.”

Tarantino himself told Charlie Rose that Hollywood used to be the best place in the world for telling stories, but it was the worst now. “We don’t tell a story, we tell a situation,” he said. If you know what is going to happen in the first few minutes, “that’s not a story. A story is something that constantly unfolds.”

That is what Pulp felt like at 30.