The other day, I found myself skimming through Shakespeare’s Richard III, the tale of a king who was vainglorious, scheming, and amoral. Breaking the fourth wall to confide in the audience, Richard makes a shudderingly fine villain. Breathless, we follow his Machiavellian rise to power and short, destructive reign.

The opposite of a slick, expensively suited woman-grabber, Richard has a crooked spine and his legs are of uneven length. His cast of mind is bitter—and as honest with himself as his worst enemy would be. He is “rudely stamp’d,” he confides, “sent before my time into this breathing world scarce half made up.” Lonely and shunned, he cannot “strut before a wanton ambling nymph”; even dogs bark as he limps past.

In other words, he has not had all his material and physical wants sated. Nothing has turned to gold for him, and no golden helicopter will rescue him from the ruins of his ambition. He has reason to be bitter.

He also, for all his villainy, has a soul, and enough self-knowledge to chart its loss for us. “I am in so far in blood that sin will pluck on sin,” he says a few murders into his journey to the throne. His ability to confess the grievousness of what he has done turns a history into a tragedy. Rather than being self-absorbed from the start, Richard was driven inward, and since he cannot prove a lover, he tells us, he is determined to prove a villain. Since no one can love him, he must love himself above all.

I dig out an old videotape of the play and watch Richard’s dissolution. The questions that come into my mind are familiar ones of late: Has he gone mad? What will he do next? Is there anything he will not do? At one point, he tells us, “My conscience hath a thousand several tongues,” each one condemning him. Later, he decides that “conscience is but a word that cowards use, devis’d at first to keep the strong in awe.”

Richard had humanity, but he deliberately discards it, death by death. And while I cannot excuse his bleak, inexorable decision, I find myself mourning it with an empathy today’s politics have not engendered.

Yet there are similarities.

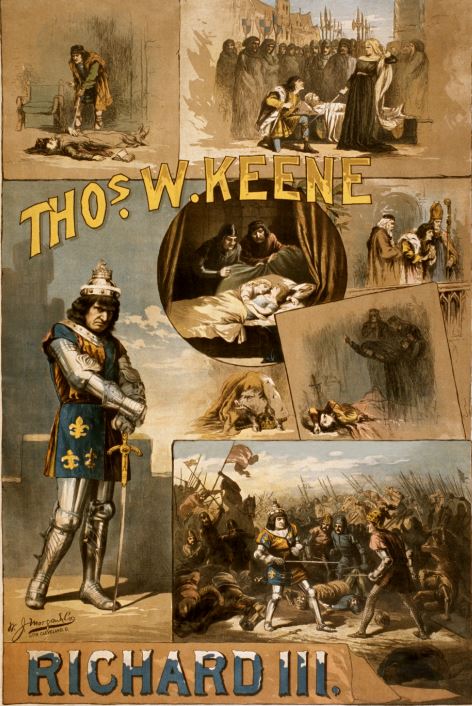

Literary critic Paul Haeffner described Richard’s speech to his soldiers as “slangy and impetuous”; an individualist, he hates dignity and formality. He surrounds himself with priests for effect, bookended by them on the balcony in the Laurence Olivier version, and he pretends virtue to please the holy: “And thus I clothe my naked villainy with odd old ends stol’n out of holy writ; and seem a saint, when most I play the devil.” He lies easily, with bold and almost cheerful confidence, to further his own plans, and he goads others into vile acts on his behalf. He knows, I see with fresh eyes, exactly how to work a crowd.

Increasingly paranoid, Richard grows less and less popular. His speech loses its wit and liveliness. “Thou art a traitor: Off with his head!” he yells, and those around him begin to cower, wondering who will next be cast out or killed. He promises an earldom and valuable goods to Buckingham, his most loyal ally, and Buckingham gladly helps him secure the throne—only to have Richard refuse to pay his bill.

By the end of Act IV, the king is alone, having alienated or been deserted by everyone around him. He has even stopped interacting as often with us, his audience. No longer going near that fourth wall, he is stuck, isolated, moribund. We watch in similar paralysis.

The Folger Shakespeare introduction calls Richard III “a moral holiday.” For four acts, “the play draws us to identify with Richard and his fantasy of total control of self and domination of others.” In Act V, we see the consequences. Richard’s soul, twisted and wrung dry, has shriveled. Fate now takes its turn.

A general who has triumphed on the battlefield despite his disfigurement (and with no mention of bone spurs), Richard must resort to violence to keep his throne. He dies fighting for his crown, which has rolled off his head into the shrubbery. By now he has already admitted, aloud, that no one loves him, and why would they, he continues, when he is such a ruin he does not even love himself. Donald Trump’s followers saw him not as Richard but as King Cyrus, the nonbeliever who would, as evangelical author Lance Wallnau put it, “restore the crumbling walls that separate us from cultural collapse.” Yet little has been restored, and we have come far closer to collapse.

Richard’s acts are far more heinous than Donald Trump’s petty sins, yet Richard shows more courage and more subtlety, not to mention a fuller grasp of reality. Rather than fall into a pouting, narcissistic sulk, he shakes himself out of self-pity and leads his troops into battle. When all is lost, he grasps the truth with a wry laugh: “A horse! A horse! my kingdom for a horse!” All that blood shed to win his kingdom, and now all he wants is a horse.

The destiny he crafted so carefully has been taken from him. And he remains capable of seeing the irony.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.