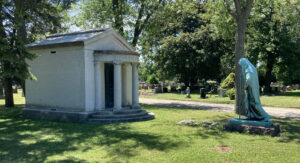

‘The Pilgrim,’ by Albin Polasek, at Bohemian National Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois. CC-Share Alike 4.0 International

Sometimes with a little concentration it seems almost possible to hear the groan of the planet beating into the solar wind, iron-melt churning around its core, seas sloshing in its holds, or to imagine 20 billion distant galaxies fulfilling their own complicated orbits like fate. And here I am, I think, sitting on my secondhand couch, waiting for the toast to jump up and scare me.

When my scale gets out of whack—domestic life bullied by a universal preponderance or inner life swelling to block out the physical world—I find it is time to reintroduce one realm to the other. It is cause for pilgrimage.

Pilgrims have many possible motives: Purification, penance, nearer my God to thee; an enactment of self-motivation, curiosity, good intentions; virtue signaling, bragging rights. Being on the road ain’t mucking out stalls back in Essex.

Still, what most pilgrimages share is a recalibration of the inner and outer (mind/body, spirit/flesh, self/other) when those begin to feel like unhealthily distinct realms. Peter Matthiessen undertook one after the death of his wife by cancer; Chekhov journeyed to Sakhalin, and Bashō walked his narrow road to the interior at difficult times in their lives. Looking back, I would say most of the long trips I have taken were pilgrimages, whether I knew it or not, especially to literary Russia and Japan, and to Vietnam, where I was born and my nuclear family ended. The real goal, apart from seeing the houses of beloved writers, museums, the stone stairs to the temple the master climbed 400 years ago, was not to emulate those people or bring back the past; it was in hopes of learning about the act of seeing and being better able to articulate the experience of being alive.

It is an odd season for me, so I cannot help but do some accounting. Both my sons are off to university soon, and I am recently divorced, so I will be living alone for the first time since I was 25. I am reasonably fit, in good health, and am never bored when alone with my mind. (My sons think I am like Puddy, on Seinfeld, who stares vacantly at the seatback in front of him on flights.) I am thankful to be mostly happy, a privileged position in our age, even as I process losses including the recent deaths of two young friends, and the waste of time, resources, and emotional investments elsewhere.

Given all that, and with nothing keeping me in one place, I will be driving soon to the East Coast for a clear-my-head, start-a-new-chapter, see-old-friends-and-new recalibration of the inner and outer realms—a long pilgrimage of sorts with hot spots of interest, which I hope to write about here.

Pilgrimage has connotations of self-scourging, but this does not have to be the case. It can mean simply traveling-by-reflection: “clear-eyed analysis, humility, and willingness to journey with open eyes and an open heart,” as one of those young friends wrote. It means doing real work through invented work, the way you always find books that change your life when in the library hunting sources for a research paper.

All of human life, it seems to me now, is a gathering of such importances. Some seem inconsequential in practical terms, and some reveal themselves to be false in time, but the effort is never a waste.

A friend asked recently if I saw the glass half-full or half-empty. It occurred to me the question is moot. When we widen our view, the glass sits on a table in a lovely city at the foot of a rumbling volcano. The city is built on a much older city, which was destroyed as the new city will be. Dogs bark, children play, the new vintage will be fine, they say. Our life is the glass, never mind our estimation of what is in it, as is the table, the dogs, the layered cities, the volcano, and the sea and all its fishes, on a planet moving 19 miles a second, in the solar system moving 124 miles per second, in a galaxy moving 370 miles per second. Beyond that, how do we measure speed at all except in relation to others, or decide which journeys are significant?