The new documentary Becoming, released May 6, is the second film from Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions, which signed with Netflix in 2018. Their first film (see my review here) was American Factory, which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature last year.

American Factory’s power came from showing the culture clashes that resulted when a Chinese corporation set up shop in Ohio with American labor and Chinese managers. It was possible to watch that documentary without knowing the Obamas were involved, unless you saw the extra material at the end.

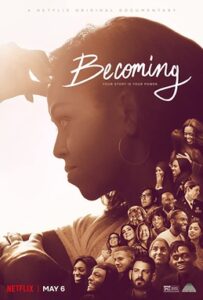

Becoming, on the other hand, springs from and directly portrays their celebrity. The film, directed by Nadia Hallgren, follows the former First Lady on parts of a 34-city book tour for her 2018 memoir of the same name, which became a number-one New York Times bestseller and won a Grammy as an audio book.

We get to see Mrs. Obama’s family photos and the inside of the working-class home where she grew up; meet her mother and older brother; hear about her father, grandfather, and young Barack (a nerdy-smooth guy with a big smile); and watch her speak with kids around the country about believing in themselves and having hope.

A girl in a roundtable discussion with other teens asks Mrs. Obama how she will return to her life before the White House interruption. Obama says her old life is gone. She is working on forging a new path—the “becoming” of the title, always a work in progress—and that she is therefore just like them. The girls love to hear it.

In fact, much of the film is shots of adoring faces—in stadium-sized crowds at book talks, in lines for signings, in mentoring sessions—nodding, smiling, weeping, sometimes all at once. Often their reactions do not seem to match what Mrs. Obama is saying, as if the film’s editors have jumbled visuals and audio for heightened effect.

Mrs. Obama is always kind and composed. She offers little vignettes meant to convey meaning about all our lives, such as the one about her telling the White House butler corps to dress-down from full tuxedos so as not to give her children false notions about life. But much of what she says to audiences is platitudes like, “Your story is what you have, what you will always have. It is something to own,” or, “Becoming is never giving up on the idea that there’s more growing to be done.”

With interview partners such as Oprah and Gayle King, the talk sometimes sounds like daytime-TV prosperity gospel that will soon be followed by a commercial message from our sponsor. In this case the network, the show, the sponsors, and the product are the Obamas.

This does not lessen the importance of the film in showing viewers an African-American power couple at their elegant, graceful best. But when it is time for inspiration to move toward specific goals, platitudes are of limited use. One young woman asks Mrs. Obama about trying her hardest but no one will take her seriously. Obama corrects her and says to believe in herself first—as if self-confidence is the only factor.

Elsewhere Mrs. Obama tells the story of how she is still “salty” that her high-school guidance counselor told her that Princeton was aiming too high. She does not explain how she applied and got in anyway without school support.

The problem with celebrities as role models is that most of us will never become anything like what we think we adore. None of Mrs. Obama’s fans will ever become Michelle Obama, after all. She herself would not be Michelle Obama but for her random encounter with Barack, when both happened to work at Sidney Austin LLP. Even as a partner in a big firm, she likely would never have found the same enthusiasm for any book she might write, or the chance to be celebrated on this scale. Without her, Barack likely would not have become President.

In fact, one very real answer to the girl who asks about being taken seriously comes later in the film, when Mrs. Obama mourns her grandfather, whose intelligence and talents were ignored and wasted. It is both tragic and common, and the film ignores that in the present.

Becoming also does not seem to understand that it shows some of that at work in Mrs. Obama’s own life, as fortunate as it has been. It is well known she was forced to make the hard decision to step away from her own career, in order to support her husband’s. Then there was the aftermath of an early “misstep,” in which she said, on the campaign trail, “For the first time in my adult life, I am really proud of my country because it feels like hope is finally making a comeback.” Conservatives immediately went full-conniption, and Mrs. Obama was in effect silenced. In the documentary she explains that everything had to change, from speaking only from teleprompters to dressing in new ways. The footage from those days shows her unhappy at not being able to be what she was.

Even now, for all her intelligence, articulateness, and seeming freedom from the responsibilities of the White House, she clearly feels she cannot speak her mind. The most interesting parts of the film are where self-restraint slips, such as a flash of frustration or even anger that African Americans did not support her husband in greater numbers, or the startling though understandable aside that she thinks about her Secret Service detail being shot to death, and she would like to know where their guns are in the SUV.

This film had an unfortunately-timed release. It seems to have been meant as celebration and inspiration. But the world has changed radically since the Obamas’ two terms. What can be said about us now? I would pay to hear the Obamas speak a lean, hard language of our great becoming.