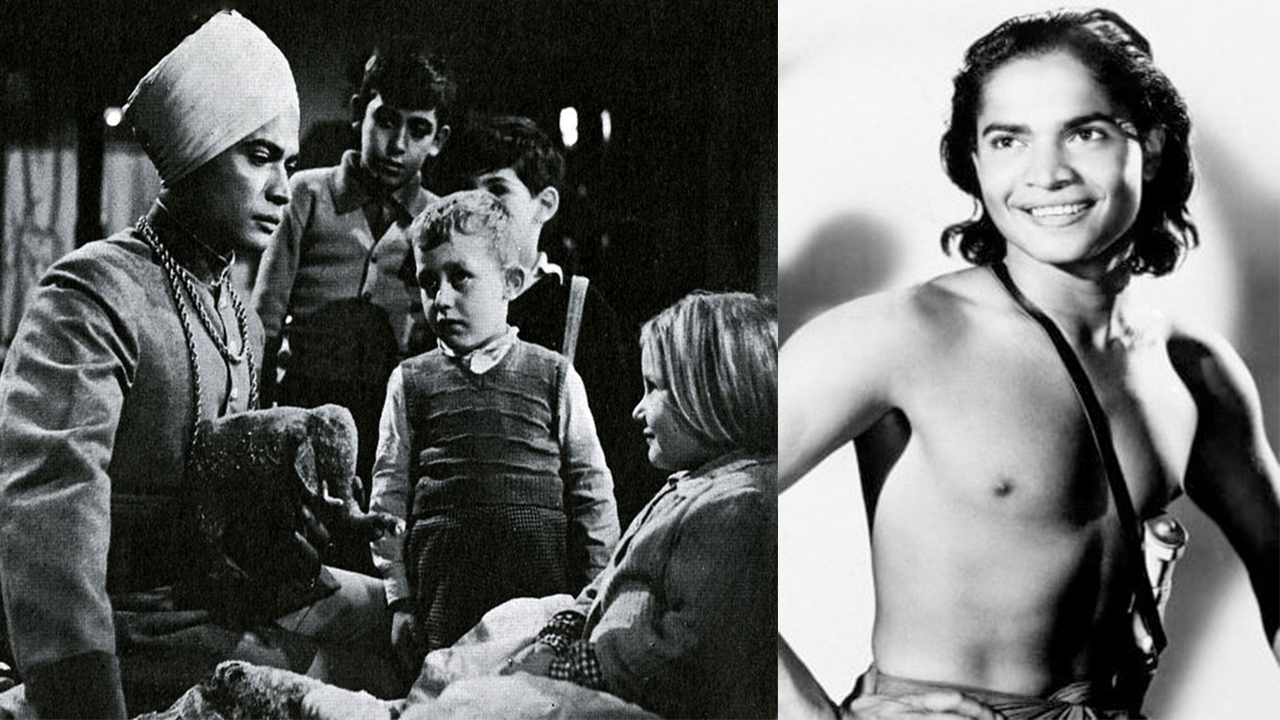

Selar Sabu in the 1952 film Hello Elephant (left) and in a Hollywood screenshot: “He was utterly gorgeous, not just his looks, but his manner, his air, his aura.”

- Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me

Selar Shaik’s great ambition as a child was to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a great mahout, a keeper and driver of elephants, for the Maharajah of Mysore. He mounted an elephant for the first time at the age of three. He was swimming crocodile-infested waters of the Karapore jungle at four. He was comfortable in this natural world. He learned how to master his father’s elephant by the age of seven by watching his father and the other mahouts closely. He could teach elephants tricks. He had the instincts, the talent to be a gifted mahout. Then, his father, Ibrahim, died that year and his elephant’s grief was so great, as trained elephants can acquire a great attachment to their drivers, that Selar had to let him return to the jungle. His older (by twelve years) brother, Dastagir, was a cab driver in the city of Mysore. He had no other relatives. So, Selar, the Muslim boy, became a ward of the Maharajah. He rebelled against schooling, attending with the greatest reluctance. He wanted only to be with the elephants. And this he did in his free time.

In the spring of 1936, filmmaker Alexander Korda sent his younger brother Zoltan to India to assist in the shooting of Rudyard Kipling’s story “Toomai of the Elephants.” Peter Flaherty, director of Nanook of the North, had originally partnered with London Film Productions and the elder Korda to shoot the film. A problem arose because Flaherty had shot thousands of feet of film, some amazing footage of elephants in India, but had no story, certainly nothing resembling Kipling’s story that the studio had paid £5,000 to Kipling for permission to make. Zoltan Korda was a good hand at crafting stories for film. In effect, he took over as director of the film in India and when filming continued in London. Their biggest need was to find someone to play Toomai, the elephant boy. Selar Shalik, 11 years old at the time, thought he was the person to do this. He had never seen a movie. In fact, he did not know what a movie was.

A cameraman spotted the youngster at ease among the elephants and was immediately impressed, not simply by the way he handled the elephants but by his personality. His screen tests bowled over Korda, Flaherty, and everyone connected with the film. He was absolutely the most winning child they had ever encountered. He was, well, utterly gorgeous, not just his looks, but his manner, his air, his aura. Selar Shalik did not speak a word of English. He learned all his lines phonetically. (He even offers a monologue at the beginning of the film.) The way he spoke English was gorgeous too, accented, just a little stilted, as if the language were a wild discovery for him, to be tamed like the elephants but respected for its power, as the elephants were.

None of the great Hollywood child stars—Shirley Temple, Jackie Cooper, Jackie Coogan, Freddie Bartholomew, Margaret O’Brien, Mickey Rooney, Elizabeth Taylor, Dean Stockwell, Roddy McDowell, McCauley Culkin, Drew Barrymore, Joel Osment, Butch Jenkins, Robert Blake, William Thomas, Jr., Stymie Beard, Ernest Morrison, Judy Garland, Baby Marie—could match Selar Shalik’s performance in Elephant Boy (1937). He was riveting. The audience could not take its eyes from him. His joy at riding the elephant (Kala Nag), his sadness at his father’s death, his aspiration to be a mahout despite not being taken seriously by the mahouts on the elephant hunt. He embodied so perfectly the innocence of childhood. He was so unaffected in his acting, so naturally reveling in the miracle of his humanity and the rude nature of the jungle that he seemed a wholly pure being, almost transcendent. When the mahouts hail him at the end for his bravery and for being the only one among them to have seen the elephants, he bursts into tears and the audience does as well. He was unforgettable. When eden ahbez wrote the song “Nature Boy” in 1947, he probably did not have Selar Shalik of Elephant Boy in mind, but he would have been a perfect muse and subject for it.

Elephant Boy was a huge international hit. The Korda Brothers (Alexander, Zoltan, and set designer Vincent) knew they had a star on their hands with Selar Shalik. He joined a long list of celebrities—Cher, Sting, Twiggy, Pele, Donovan, Madonna, Charo, Capucine, Adele—to be known by one name. Alexander Korda renamed him Sabu, the name by which he became known to the world.

- The Return of the Native

It is said by most critics that Sabu’s career started going downhill during World War II when Universal used him as beefy Jon Hall’s impish but attractive sidekick in several Arabian fairy tale movies that also starred Maria Montez, known as the Queen of Technicolor. (Actress Rhonda Fleming was also called the Queen of Technicolor.) After that, with the exception of Black Narcissus, the films became embarrassingly bad. He also found it increasingly difficult to get roles after he was dropped by Universal in 1946. Actually, the declension started as soon as he made his first picture after Elephant Boy. He made such a compelling impression on the public in his first film that he was never able to escape it and never able to duplicate it.

He made three more films with the Korda Brothers, with whom he made his best features: The Drum (1938), The Thief of Baghdad (1940), and stories from Kipling’s Jungle Book (1942). The Drum by English novelist and playwright A. E. W. Mason was the sort of pro-British colonialism confection at which the Korda Brothers excelled. (They were to make Mason’s The Four Feathers a year later, the fourth film adaptation of the novel, unattractive politics wrapped in a rousing, well-crafted adventure film.) In The Drum, Sabu plays an Indian prince whose father is killed by his fanatically Islamic, anti-British brother, played by Raymond Massey. (Many White actors adopt brownface in these films). Sabu, on the run and forced to abandon his royal garb for the bare-chested look he became known for in Elephant Boy, is aided by a British diplomat and his wife. Massey’s character plans a massacre of British troops in his province to show his people that the British are not invincible. Sabu helps save the day for the British, by risking his life to warn the British of the attack. The pro-British sentiments led to riots in some theaters when the movie was shown in India. In this film, Sabu was a bit older than he was as the elephant boy, but he still possessed that warm, smiling, personable screen persona, the charm, and the innocence. He remained intensely likeable. The added dimension is that as the heir to his father’s throne, he must exhibit some qualities of leadership and command. Thus, a thread of maturity in Sabu’s manner. (He would play a prince in a relatively minor role in the last quality film he in which he appeared: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s highly acclaimed 1947 production of Black Narcissus.) Probably what made some Indians dislike the film, aside from its pro-Empire sentiments, was that Sabu seemed a highly assimilated Indian. His best friends are a British drummer boy who teaches him how to drum, and the British diplomat, the hero of the film, and his wife. Although he is the leader of his people, he seems removed from them in some respects, as may be inevitable for someone exercising authority over someone else. His loyal personal guards in the film are not companions in the end but subjects, as he must remind them. He must also remind them that they cannot decide what is in his best interest because they are adults. The issue of Sabu’s character’s detachment from his people is complicated in The Drum and probably, because of the Kordas’s pro-British affinity, not taken as seriously as it could have been.

Sabu and his brother, by this time, were living in England. Sabu was going to school, rapidly perfecting his English, living in an apartment that was better than anything he ever had in India. His life was materially much improved, and he was mostly surrounded by Whites. He very much liked this different world. In time, he would marry a White American woman, convert to Methodism from Islam, become an American citizen, and fight for his new country during World War II. There are two contrasting ways of looking at this: the first is that Sabu was a cosmopolite, shifting easily from my cultural orientation to another, a truly “multi-cultural” person. The second is that Sabu had “gone native” in a reverse sense of how this phrase is typically used, becoming a westerner now that he was in the west. Generally, “going native” is frowned upon. (The irony is that Sabu was perpetually “the native” in his movies.) In 1953, when he returned with his family to do a film in India, his reception was decidedly mixed, celebrated on the one hand as the successful native son but reviled on the other as a cultural sellout who did not even remember his native language. According to Sabu’s biographer, he played along with being the deracinated Indian until “he was overcharged for something, when he would suddenly reveal a startling fluency in that ancient tongue.”¹ In a sense, as a result of the role he played in his first film and how he was cast subsequently, what he was as an actor became inextricably tied to what he was as a person, more so than with many others in his profession. So, authenticity, the obsessive quest of identity became an especially complex problem for him.

Thief of Baghdad and Jungle Book were developed by the Kordas with Sabu principally in mind. They were both fantasies, well-made, exotic “Oriental” fare of the sort that would trap and retard Sabu as an actor for the rest of his career. These films did have flying carpets, genies (Black American actor Rex Ingram played the genie in Thief of Baghdad), flying horses, and talking animals, which Sabu’s later films would lack, but the Middle Eastern settings and the Orientalism would remain. A lot of pop culture Islam with elaborate salaam gestures, praises to Allah, even, in Walter Wanger’s Arabian Nights, Sabu on horseback exhorting the deposed hero-caliph’s army with “Allahu Akbar.” The template was now firmly established: Sabu is the plucky, personable jungle boy who is at home in nature in a loincloth; Sabu is the playful sidekick of a prince or king unlawfully overthrown by a usurping brother or conqueror. Sabu ultimately helps the exiled prince, caliph, or king, in reduced circumstances, to regain his throne and his true love.

(An aside about these Hollywood sheik/caliph fantasy movies and those generally dealing with the ancient world, whether fantasy or realistic: Blacks are almost shown at least well into the 1960s, Joseph Mankiewicz’s 1963 epic Cleopatra is an excellent example in the latter stage, as slaves. This, I assume, is in keeping with White southern belief used to justify American slavery that Blacks had perpetually been slaves throughout human history, were non-entities in history. I guess such depictions, no matter how historically inaccurate or ethnically degrading, were to assure filling southern theaters with Confederate bottoms. No wonder so many Black Americans thought for such a long time that the south won the Civil War!)

What Sabu’s films offered was either a variant of the jungle movie or an Orientalized variant of Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper. All of his Korda films were commercial and critical successes, but other White filmmakers had no real idea how to use him in a film except to do cheaper and simpler (or campier or more inept) versions of what Kordas had done. How can he be cast differently when audiences will only accept him in this way, goes one version of the argument. But the response is, how can audiences learn to accept him in something different if he is never permitted a different role? Once he left the Kordas, a reality he could not avoid made things more difficult for him: in a White, racist film world, he was no longer a cute, winsome boy but a dark-skinned young man. By the time he started his Universal career, he was eighteen. (This is alluded to in Arabian Nights, his first Universal feature, where his character tries to enter the harem to speak to Maria Montez’s character, the film’s heroine, but is stopped by the guard. “But I’m not a man. I’m only a boy,” Sabu’s character protests. “Boys grow fast,” the guard responds. A racy double-entendre that makes the point about Sabu himself.) To remain in films, he had to remain something like a boy, a combination of a male version of a Third World ingenue and a jungle Huckleberry Finn.

When Sabu left Universal, it was commonly thought that Turhan Bey, an Austrian actor of Turkish and Czech-Jewish descent with a racially exotic look, known as “the Turkish delight,” would replace him. Bey, in fact, replaced Sabu in the 1944 film Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, starring Jon Hall and Maria Montez (that duo made six films together,² the Bill Powell and Myrna Loy—or the Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell—of “sand and sword” spectacles). Sabu was in the military at the time. But Bey, although he played a greater range of roles than Sabu, even playing against White female leads, was not the presence in Ali Baba that Sabu would have been. He lacked Sabu’s enchanting delinquent aura. To be sure, the actors were not interchangeable. In Sudan, a 1945 desert celluloid bonbon with Hall and Montez, Bey is actually the romantic lead who wins Montez’s character in the end, something that would never have happened if Sabu had been cast in Bey’s stead. There are three reasons for this: first, Bey was not a “jungle” character in his films, never in a loincloth. In fact, whether he was a villain or a heroic character, an undercover agent, a con man, or a religious fanatic, Bey was usually an “Oriental” or “Eurasian” type, representing the ambiguity of urbanity. Second, Sabu embodied youth, boyishness, that Bey never did in his roles. Finally, the indistinctness of Bey’s appearance, of his racialness, its all-purpose “North African” quality, so to speak, made it easier to cast him romantically against a White female lead without audiences being made uncomfortable at the thought that the relationship was interracial. Sabu’s darker skin and “Indianness” would have made such a venture riskier. Bey’s career petered out in the early 1950s, not to be revived until the 1990s.

Sabu would remain in films until 1963 when he made his last film, a Disney feature, called A Tiger Walks. The same year he died of a heart attack at the age of 39.

• • •

¹ Philip Leibfried, Star of India: The Life and Films of Sabu, (Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media, 2010), 193.

² Turhan Bey actually appeared in more movies with Montez than Hall did but Bey’s character was not always paired with Montez as Hall’s always was. In some of the films, both Bey and Montez were minor characters.