The wake of a car ferry in the Long Island Sound. Photo by John Griswold

I was sitting at a café table outside the pâtisserie in Little Morocco, Queens, waiting on repairs to my aging Honda, when an older man in shades pulled up to the curb in a no-parking zone, in his black Cadillac Escalade Premium Luxury Platinum. I was thinking about mobility, you see, so the universe manifested him, though to be fair he manifested every morning and was doted on by the bakery staff.

I had been thinking about how long I had wanted to see the Connecticut coast, where my Griswold ancestors—the middle portion of an unbroken line of fathers and sons going back to the year 1200—first arrived in the Americas, but I was not planning to visit on this trip. It felt like a missed opportunity, but the drive was already long, and, besides, I knew my end of the story.

The man came back out of the bakery with his customary pain au chocolat and an espresso in a Styrofoam cup, got back in his SUV, and motored off down the main channel of Steinway Street. For no reason it struck me: There is something called the Long Island Ferry; I had heard of it as far away as Illinois. I had a hunch then and checked my phone. Sure enough, the Cross-Sound ferry sailed multiple times each day from the eastern tip of Long Island to New London, Connecticut. I could still catch it this day after I picked up my car.

Why did not somebody tell me how lovely Long Island is? Passing Massapequa, hometown of Jerry Seinfeld and Alec Baldwin, then Amityville, traffic was light and flowed easily through the woods. Part of the point of long travel in unknown territory is mental bending, but the chance to relax is welcome.

The woods became pine barrens. I took the exit for the North Fork of the island, which is to say away from the Hamptons, and drove for half an hour. The Long Island Sound was somewhere to the left, the Peconic bays somewhere to the right, but it was not until the expressway ended at the town of Orient that I smelled the sea so strongly I nearly drowned of nostalgia. Just then my GPS gave out, and three locals at the Mobil station got involved to tell me how they would drive the remaining miles to the ferry at Orient Point: past Sound Avenue’s vineyards, farms, and markets, until there is the actual Sound, blue under a blue sky, uplifting to the soul.

The ferry, MV Cape Henlopen, was actually the old USS LST-510, used at Omaha Beach on D-Day, with a newer superstructure. Another good omen, I thought, since my father would certainly have been on LSTs in his service in the Pacific Theater. The ship steamed across the Sound with its belly full of expensive cars and mine, up the Thames River, and past the old Fort Griswold. I texted my sons to say another Griswold had just arrived on the shore of America. We disembarked, and I drove west to the Connecticut River.

A man and his son walking their dog on a small road in Old Lyme caught me up on the Griswolds who lived in the area—“400 years of judges, statesmen, and doctors,” he said. “Eleven or 12 of the families still live down at the end of that road, where there are a bunch of mailboxes. The meadow you’ll see on the way there, the one where you catch the first glimpse of the Sound, was part of property all around here given to the family by the King.”

Photo by John Griswold

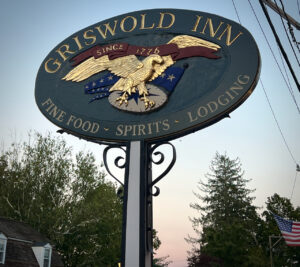

I went that day to three or four of the sites associated with the Griswold name, including a graveyard and the Griswold Inn, which opened in Essex in 1776 and has never closed.

“I’m a Griswold too,” I told the hostess at the restaurant under different management now. “One of the poor relatives, from the Illinois branch of the family.”

“Yes, we get lots of those,” she said.

For years I have been reading haphazardly about my patriarchal history and thought I knew the story. My great-times-seven grandfather, Edward, and his brother Matthew came from Warwickshire, England, in 1630 on the Mary and John, in the Puritan Great Migration. Edward served as a member of the colonial legislature, a commissioner, and a business/land agent.

I figured the ship had sailed directly up the Connecticut River, and that Edward and company had founded a dynasty that later included iron and steel magnates (who also built the USS Monitor and manufactured those cast iron skillets still in demand), US Representatives, governors, a president of Yale, and a Confederate arms maker. But this trip helped me better understand: They sailed to Boston first from England, and after nine years may have gone overland to the Connecticut coast, where the (now three) brothers and their families began living separate lives.

Edward, though he is described as a “founding father of Connecticut,” seems to have tired of politics and public life; he served on at least two witch trials that called for death sentences and is mentioned in early colony records about division in the church. He and his sons moved farther out, away from developing centers, into what was still considered dangerous territory. Then he and his wife, Margaret, left that homestead to their sons and moved, yet again, down the coast to what is now Clinton, Connecticut.

A genealogical site says, “[I]t is possible that the love of peace influenced his going to a new place.”

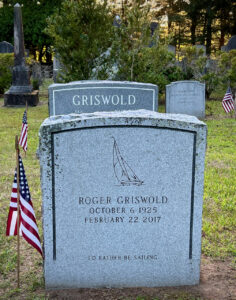

Margaret died in 1670, Edward at the age of 84, in 1691. They and members of their family are buried in Clinton. When I visited their graves, the oldest in a beautiful old cemetery, I made some brief remarks, and a fife began playing from a source I could not locate.

Distant relatives in Old Lyme, CT. Photo by John Griswold

Several generations after Edward, in about 1820, his great-great-great-grandson, Gilbert, began walking westward, once again displaying a penchant for mobility, adventure, and a slow march to generational poverty. Many of the Griswolds who stuck to the neighborhood of Essex got involved in shipping, the China trade, and the politics of the new nation. Gilbert helped found a small town, once named Griswold, in Southern Illinois, but his grandson, my father’s father, also named Gilbert, was a sharecropper in hardscrabble Little Egypt, Illinois.

This tendency to movement, as opposed to staying put, is not the whole story of inheritance, and inheritance is by no means the whole story. But let’s just say I can relate. I ended my visit to Connecticut Griswold country and struck out again in the direction of the Alleghenies.