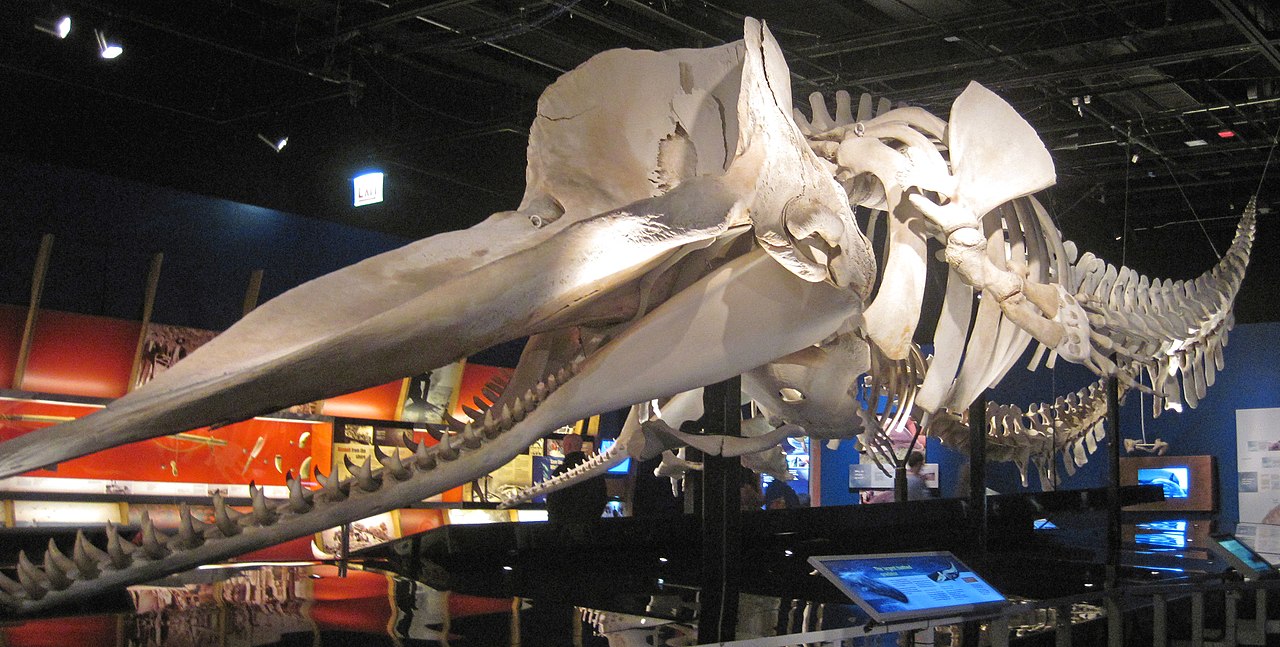

Sperm whale skeleton, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago (courtesy James St. John, CC 2.0 Generic)

Avast: Spoilers dead ahead.

A revival of a play of Moby-Dick, adapted and directed by David Catlin, is in its last week at the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis. The original production was staged at Lookingglass Theatre in Chicago in 2015 and again in 2017. This one is a road show for that company, which made an announcement last year, startling to many in that theater town, that it was in “transition” and had laid off half its staff and suspended most home productions.

Adaptation is always an act of translation, and choices must be made, especially when the host text is (in the Norton Critical Edition) a 427-page anatomy of cetology, voyaging, and human existence, heavily inflected with Shakespeare, Milton, and the King James Bible, with another 300 pages of essays, definitions, illustrations, etc., deemed necessary to understanding the novel well. Despite its moderate difficulties, the book is one of the towering works of the human spirit, a book for the ages.

By necessity, the three-hour production leaves many characters and scenes at the dock. It combines others, and focuses on plot and the monomania of Captain Ahab. As Brian Yothers, a Melville scholar and the department chair of English at Saint Louis University, told me, the play “conveyed Ahab as King Lear very well (perhaps not Ahab as Milton’s Satan quite as much).” I registered the play as much grimmer than “my” Moby-Dick, almost in line with the Classics Illustrated graphic novel I also have at hand. Dr. Yothers told me the play “leans… toward Gothic melodrama, which fits with the emphasis on spectacle that comes with such an athletic performance.”

Still, Yothers says, “[I]t provided an introduction to MD that I think conveyed many of the strengths of the book (including at least to some degree its multi-generic quality) in a way that can help audiences who find the scope of the book overwhelming to understand its complexity and appeal. [R]eaders can find the book too vast and multifarious to find an entrance, and this performance gives a very fine point of entrance, similar to what a very good teacher might provide.”

I saw Lookingglass’s Treasure Island at their home in Chicago’s Water Tower Water Works in 2015. The set was impressive for a relatively small space; the Hispaniola was a realistic ship that could be rolled (with significant effort) atop invisible waves by cast members using long poles, and the cast moved around the ship and on “land” athletically.

This Moby Dick too is muscular, even acrobatic; one cast member described it in the talkback as “circus theater.” The Pequod is only a bare deck suggestive of a ship, with stylized rigging rising around it, haloed by whale ribs overhead. Actors climb and dangle from the lines, raise themselves with pulleys on scaffolds they “row” like longboats, and somersault and struggle on the stage.

The most visually-noticeable choices have to do with the biggest things in the story: the sea and the white whale. The sea at times becomes a woman (Bethany Thomas) in a formal skirt the size of the stage; cast and crew billow her wine-dark fabric like waves. This is most moving at the moment of the ship’s destruction, when the sailors walk to her one-by-one through the skirt-waves, receive a kiss on their foreheads, and sink out of sight, a return to mother. (Think of homonyms such as “la mer” and “la mère.”)

Ishmael (Walter Owen Briggs) tells us early on that a sperm whale would be as large as the auditorium we are sitting in; its magnificence simply will not fit, so we must rely on our imaginations. It comes as a surprise then, near the end, when the whale, represented by heavy white cloth nearly the size of the theater, flies in from behind the audience, passes overhead, and envelops the stage. (I was reminded of the opening of the first Star Wars, which blew the minds of theatergoers when that first Star Cruiser advanced onscreen from overhead, an image unusual and vivid for films of its time.) In Saturday’s performance the whale malfunctioned, hung on its trolley, and dropped hilariously on our heads and laps. I was glad to finally encounter the white whale.

Melville’s Moby-Dick is sometimes decried now because it portrays a whaling ship with no women on it. By the time the novel was published, as many as one in five whaling ships had a woman aboard—but only the captain’s wife. Brian Yothers told me, “I have always been skeptical of the view that Moby-Dick is inherently a hyper-masculine novel, and I think my skepticism is borne out by the fact that a very good percentage of the finest Melville scholars over the past century have always been women.” The women, I would argue, are present in their absence and are often the definition of home.

This production brings (three) women onstage often, not only as the sea but also as whales, the weather, a chorus, and the Fates/Furies. They are frightening as often as moving, and their symbolism and judgement upon the action cannot be missed. The choice was made, for instance, to “slaughter” a woman representing a whale, equating the maternal in the scene with nature itself in our current age of extinction.

Overall, the play does well portraying one of the novel’s main conflicts: that Ahab cannot live without knowing, within the framework of his own understanding of cause and effect, and this tautological pride makes other beings suffer. His lust for vengeance is blasphemous chiefly because he cannot live in The Mystery without acting on some little part of it and calling it the whole—just like us.

Moby Dick, the play, runs through February 25, 2024, at The Rep.